It’s never a good sign when your day starts with over 200 unread Whatsapp messages. Last Friday (June 24th), I woke up to news that I and my friends on the Liverpool Whatsapp group had thought would never happen: the UK had voted to leave the EU. Even after the initial whirwind round of messages sent in the early morning hours, the rest of the day was spent reading news articles and seeing the shock and disappointment from UK and European friends on Facebook and Twitter. With the flood of posts swirling around in the past few days, I wanted to take the time and think about what Brexit will mean in the context of the type of work that binds me and many of my UK and European friends together: science.

There will be numerous direct effects of leaving the EU on science here in the UK, on everything from the availability of grants, the mobility of professional researchers, and the scientific infrastructure that’s been set up within the EU. As I read these articles and numerous other ones like them, I empathize with my friends who are in the process of developing their own careers in science here. How can you manage additional uncertainties in a field where you already have to spend so much time worrying about grants, short-term contracts, and competitive jobs? The flood of news articles and opinions continued to pour in over the weekend from experts and scientists, but after being drained of my productivity on Friday and worrying about the implications of Brexit on my own future, I took a break from reading the news this weekend. Even so, one of the article subtitles kept me pondering the rest of the weekend: ‘What has the EU ever done for us?’ This question brought me back to the Life of Brian scene, where while planning an uprising against the oppressive Roman regime, the question is brought up of what, exactly, the Romans ever did for us. “... but apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order... what have the Romans done for us?” Romans have now come to mind a second time on our blog and for good reason. During my travels around Europe, I’ve been able to visit 16 of the other 27 EU countries, and only 9 of the 28 EU countries (still counting the UK) were never a part of the Roman Empire. In the many places I’ve visited around Europe, I’ve seen enduring remnants of Roman building projects. From the state history museum in Budapest, full of Roman artifacts found across the Hungarian plains, to the impressive and fully intact aqueduct of Segovia, and Hadrian’s Wall just a couple of hour’s drive from Liverpool, stretching across Northern England and still marking the boundary between what was Rome and what was the rest of the world. Rome was certainly not a perfect empire, but it was one that lasted for over 300 years. This is impressive for a relatively unconnected world as compared to ours, in a time without telecommunications or any transport more rapid than the horse. Even still, Rome was connected across the vast amount of land between its borders, and people were Roman despite where they had been born, what language they spoke, or how exactly they came to be incorporated into the Empire. While I’m sure not everyone had a fantastic life under Roman rule, and there were certainly a fair share of bad emperors throughout the history of the Empire, Rome as a unified concept did mean something important. As a person living in the classical period and regardless of your income or your social status, you would have been able to see the positive impact that a road or clean water had on your life. You would have enjoyed plays in the local amphitheater or the wines and exotic foods more easily available to you and your family from across the empire. You would have felt some protection at being part of a bigger unified nation than when isolated to just your village or your tribe. Being Roman 2000 years ago would have meant being part of something powerful, something beneficial, and something enduring. But as we already know, Rome didn’t last forever. The empire fell and the Western world left with warring neighbors, short-lived empires, and a period in history that came to be known as the Dark Ages. I don’t believe we’re headed for another dark age, but as history shows us we do need to recognize that history involves cycles of uprisings. But unlike the Dark Ages, we have countless sources of news nowadays, we can get facts and figures from reputable sources, and we can hear directly from experts in order to get a better understanding of the problem using sound logic and reason. Right? As we discussed in our storytelling post two weeks ago people tend to rely on emotions when making decisions. With money, a family, and a future on the line, people are not always driven by logic, facts, and figures. We are driven by emotions, by stories, and by selfish needs. Unfortunately, the Leave campaign made good use emotions and fed off the enthusiasm of an uprising, bringing together a rousing rally against ‘the man’ (e.g., the EU) that’s apparently holding us back. This line of campaigning is evident from the tweets on their twitter account and you can see a few of the tweets below:

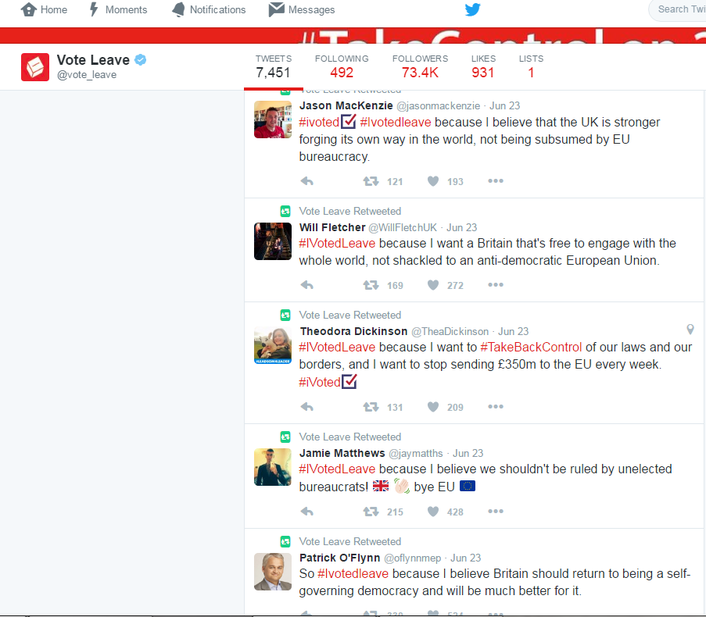

Oddly enough, there’s no equivalent @Vote_Remain Twitter account, and while there are a flurry of #Remain tweets (especially now after the vote is over), it seems that the question of ‘What did the EU ever do for us?’ wasn’t as enthusiastically addressed by the Remain campaign.

But what does this all mean for scientists? In the midst of worrying about the future of our research contracts, the prospects of losing future EU grants, and thinking our colleagues who come from every side of the world to work in the UK, we also have to recognize that in this day in age, scientists are considered ‘the man’. In a campaign that has won by fueling disregard and mistrust in ‘experts’, is it any surprise that people started to go against the recommendations of said experts? Scientists are not considered to be of a trustworthy profession, and we come off as competent but not very warm. In a recent study conducted in the UK, one person relayed this comment on why they had no interest in science: “Snobs, know it all! Better than others just because they are intelligent, boring and thinking everyone should know what they know!”. Is it then any wonder that in an age where people are taking a stand against the status quo and ‘the man’ that this also means a stand against science? If scientists want to stop being ‘the man’ that the rest of the world is up against, we need to think about and engage in the communication streams that people get. While most of the other respondents did have a general interest in science, many felt that scientists were hard to access. Events like science fairs and festivals look great on paper or on a resume, but many folks are limited in their ability or interest to take time from their own lives on a busy weekend to go and do such an activity. Many are engaged with science news in the media, but since the media also has the potential to get something wrong or to over-sensationalize something, how can we as scientists do better to share our science? If people feel like we are hard to communicate with unless we come to them in a science fair, why should we expect them to trust us as the experts when we say to them from afar ‘if you do X then Y will happen, so you shouldn’t do X’. Now is a good time to reflect on how we as scientists can do a better job at not being seen as ‘the man’ but as a member of this team, of the metaphorical Rome that is our world. Based on the results of this survey, it’s not that people have no interest in science or don’t see value in what we do, but that we’re not meeting people where they are, that we’re still stuck in ivory towers pondering all our expert opinions instead of meeting them face to face. We can spend our days post-Brexit worrying about our own grants and jobs, or blaming the other side for whatever happens next, but in a few years’ time the dust will settle on the UK’s exit from the EU, and we’ll still be ‘the man’. If we focus on getting people on our side by talking with them eye-to-eye and making them part of a two-way discussion, we can make sure that we narrow the gap between The People and The Experts. If we meet with and have discussions with people outside the ivory tower, if we engage in listening instead of lectures, we can make connections and we can build trust. Regardless of the future of the EU, the UK, and everywhere in between, we as scientists still continue to have the power to make great and positive changes in our world. Just because history tends to repeat itself, it doesn’t mean we have to repeat it completely. We can learn from how to connect with people by listening to what fuels their interests and where they want to engage with us. We can change the personal of scientists from being cold-hearted and nerdy towards a more accurate depiction: we are hard-working, motivated, and we are here to make the world a better place for everyone. Despite the turbulent times that we find ourselves in, I am encouraged by the fact that people do have an interest and are looking for information when they make decisions about their lives. And if history teaches us anything, it’s that even though Rome eventually fell, after the Dark Ages came the Renaissance. After having seen first-hand the relics of Rome spread across so many countries, I’m encouraged and hopeful that the relics of a united Europe and a united world will last well beyond our lifetimes. SPQR! Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed