I landed in Marrakech last Tuesday an hour late due to delays in Manchester, and even though I was a bit tired, I was excited to start exploring a new city. After an interesting taxi ride through narrow streets full of vendors, donkeys, and an endless flow of mopeds, I made it to my Airbnb riad (the term for a traditional Moroccan house). I was given a map and some instructions about the best way to get to the city center, just 15 minutes away. I set out into the warm Moroccan evening and soon ended up going the completely wrong way, not even sure which street was mine when I tried to retrace my steps. After accidentally running into the friend of my host who’d helped me get to the riad from the taxi drop-off in the first place, we walked together to the city center, with my enthusiasm for exploring soon turning into embarrassment at getting lost.

With my friends arriving in the morning, I wondered how the rest of the trip would go from here. Would I keep getting lost, and this time run into someone less friendly than the friend of our host? How would the rest of the trip go if we couldn’t even find our way around town? After that initial bump in the road that left me feeling anxious for the rest of the trip, I’m glad that the rest of my time in Marrakech was amazing. I soon found that the best way to get around wasn’t to have a precise plan as to what cross-streets you were going to take, but it was simply to wander through souks and side streets with a vague impression of the cardinal direction you wanted to get to. This approach led to more than a few wrong turns, but it also led to less crowded streets and shops, beautiful street art and wall decorations, and the feeling like you were really getting to see the heart of the city. The trip to Marrakech was a great experience for many reasons, not because everything went to plan, but because it was an adventure in itself: a chance to try new foods and experience new smells, to be a bit unsure of what exactly you were walking into, a time to wander and find things you never expected, and even at times a chance to fail. Whether it was museums that were closed due to Ramadan or dead ends or a store owner rather aggressively trying to sell you a henna tattoos, there were certainly things on the trip that didn’t go all the way according to plan. In the end, we found out things that work and things that don’t and kept going past the small missteps as they came. Throughout our time studying, from primary school to our undergraduate careers, we are taught how to achieve and how to succeed, and we are encouraged to do so. We get rewards for performing above the mark, we get grades and rankings based on our achievements in classes and on exams, and we’re measured on a regular basis in terms of how we succeed and how much we know. Then when you get to graduate school and find yourself in a research-oriented career, the game changes. There are no more exams, grades, or rewards of knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Grad school and life as a researcher is more about producing reliable data, generating results related to a question, and making sense of new information and putting abstract concepts together. It requires a different mindset from the one that gets you success in school: a mindset that includes being ready to fail. If you’re a PI in the US, the success rate for applications on research grants hovers around 20%, and here in the UK it’s closer to 30%. That means on average you’ve got a higher percentage chance of failing for every grant you apply for-and if you’ve never applied for a grant, it’s definitely not a small endeavor. In addition to the task of securing research funds, as scientists we’re also met with experiments that fail, manuscripts that get rejected, uncertainty in terms of a job market or a long-term contract, and criticism everywhere from your PI to people who come to your conference presentations. It’s a really difficult transition, especially for those of you for whom primary school and/or undergrad came easy, who might be naturally good at memorizing facts or taking tests but who find research more of a challenge than initially expected. But this post isn’t meant to paint research as a life of doom and gloom, of spending your days steeped in failure. I’ve met lots of colleagues who’ve been turned down for grants, but because they knew the idea was a good one and believed in the value of the project, they learned from the first round reviews and had a revised application accepted in a second or third submission. I’ve seen friends struggle in the lab for weeks or months on end, then followed by strings of incredible results that just keep rolling in. I’ve read about the hurdles that world-famous scientists had to go through or the challenges they faced in their ideas or in their careers, only to come back from a challenge with more vigor and an even better understanding of the problem than before. In one of our previous posts from last year we talked about the importance of not being afraid to fail, a post inspired from my time spent in martial arts. But it’s one thing to say ‘don’t be afraid to fail’ and another to actually follow through with putting yourself at risk for failure. How can we become better at taking that first step, knowing that after a few more steps we might easily fail at our task? As a child and through my studies as an undergraduate, I seemed to be good at all the things I participated in. But it wasn’t because I was good at everything; in fact, I was very bad at trying new things, because I was afraid of failing. I was good at the things I did because I avoided things I was bad at, whether it be team sports, dating, socializing, or getting lost. In graduate school, I learned how to fail the hard way: I took failed experiments and rejected papers really hard, but at the same time grad school became one of the most enlightening times in my life. While I was learning how to fail the hard way, I also figured out how to be braver at venturing out into unknown territories of research and of life, and I learned how to fail in a way that didn’t make me feel like I had done something wrong. But how exactly does one become good at failing? Remember that failure is part of the process. Research is difficult because you are working on the cutting edge that divides what’s known and what’s yet to be discovered. You’re not repeating the same thing that any one person has done before, so because you’re in uncharted territory there will inevitably be wrinkles to sort out and things that don’t pan out the first or fifth time around. The famous scientists that came before us also made mistakes, sometimes even a lot of mistakes, but they also know that it’s all a part of the scientific method: you have an idea, you test it, and then you figure out whether it’s right or wrong. Science isn’t about always being right, it’s about figuring out the answer, whatever that answer might be. Work on achieving a balance of optimism and pessimism. Being too much of an optimist can leave you feeling like you’ve taken a hard hit when something doesn’t work, because you’ll have gotten yourself excited about an idea or an experiment. In contrast, being too much of a pessimist and thinking that every upcoming experiment will fail can leave you feeling too unmotivated to even try. A good scientist is a balance between the two: you recognize that not everything will be sunshine and roses the first time around, but you also are inspired and hopeful for good results to come down the line. As with other times in our career when we need to achieve a balance between two sides of a coin, you can also work on achieving this balance by surrounding yourself with colleagues who might lean more towards one side of the optimism/pessimism spectrum than you do. Lower your expectations. This sounds like a terrible piece of advice, but especially if you’ve achieved a good balance between optimism and pessimism, having lowered expectations can come in handy. If you over-exert yourself by trying to get everything to work all at once or are relying on one success to raise you to another, one failure can knock you over. Take your research one step at a time and leave a buffer in terms of time and energy by taking into account that some things might not succeed. Don’t expect that something will work the first time around, and if instead you expect that you won’t get perfect results right away then you’ll know to leave some time to repeat things as needed. On the other side of the coin, lowering your expectations also means you have an excuse to celebrate the small successes. In grad school especially, it’s these small victories that can help keep you going. Had a PCR reaction work? Drinks with your lab! Got a paper that wasn’t rejected outright? Drinks with your lab! Celebrating these smaller, perhaps ‘lesser’ victories will make the bigger ones seem even more incredible and will keep you going until things start to go your way more consistently. Come at a problem with confidence, even if you don’t feel confident. This week in tae kwon do, a few other students are getting ready for testing. Our instructor was giving all of us a pep talk after one prospective red tag to red belt was clearly uncertain and nervous during practice, saying that we needed to be confident and ready even when we didn’t know everything 100%. Even the most veteran black belt will get nervous when faced with a belt testing, and it’s easy to believe we’re not doing everything perfectly, that we’ll make a mistake, or that we’ll forget something. In a recent seminar I gave on the five easy steps for a perfect presentation strategy, I asked the participants what they were afraid of the most while giving a talk, and most said they were afraid of doing something wrong. I thought back to those replies during tae kwon do class this week, and realized again just how much martial arts can teach us about being a scientist: it inspires us to live a life of confidence even in the face of punches and stern instructors (or professors) grading our every move. When faced with fear, you meet it with ferocity. When afraid of failure, you hold yourself with the confidence of a person who knows everything like the back of your hand. It’s about being ready to face a potential for failure in the same way you face the potential to succeed. Envisioning success is half of the battle, and by facing potential failures with confidence you can increase your chances of success. Don’t let a failure (or two) define you. I still get nervous for talks, tae kwon do testings, even conference calls. Before anything that makes me feel nervous, I always end up giving myself the same pep talk. I tell myself that no matter what the results are, it doesn’t change who I am. Just like the two failed black belt pre-testings that didn’t keep me from getting a black belt later on, or the many failed experiments or rejected papers that didn’t keep me from getting great data or publishing my results. What’s more important than not failing is to learn something from the moments when we fail, to celebrate when we succeed, and to not be afraid to let a couple of mistakes hold us back from getting where we want to be. Whether that’s a government lab researcher, a university professor, or the CEO of a company, the failures we have along the way won’t define how we get to the end result, and won’t solidify our fate or who we are as people. Failure is an option in science-and more than that, it’s a way that we make progress. It doesn’t have to feel like banging your head against a wall if you look at failure as part of the process instead of blaming your own faults. By approaching problems with confidence, holding back from becoming too over-zealous when it comes to thinking what might work or not, and by not letting each wrong turns define who we are and where we go, we can learn how to use failure to our advantage, and to become better scientists and people in the process.

This weekend I traveled to the Scottish Highlands and hiked Ben Nevis on an unusually sunny Saturday. On a typical weekend I try to think about the upcoming week’s blog post, but this time I had other things on my mind, namely What am I going to pack for the upcoming SETAC meeting? This seems an odd question to spring to mind while hiking the tallest peak in the UK, but it was partially relevant and inspired by the attire of the hikers that I crossed along the trail. While there are some ‘rules’ to hiking clothes, such as sturdy boots, some sun protection, and layers that you can take on and off in case the weather takes a turn, you always end up seeing quite an assortment of outfits on a hike, ranging from the fully equipped hiker with high-end equipment in all matching brands and colors to the person who just looks like they rolled out of bed and hit the trail.

For those of us that work in a wet lab setting or who spend our whole day in an office with other graduate students or researchers, there really aren’t any day-to-day outfit ‘rules’ (except for closed-toe shoes when necessary). As graduate students and early career researchers, we can easily get away with wearing just about whatever we want and as long as it’s comfortable and appropriate for your work environment, there’s little else that needs to be done. That being said, there are times of the year when all of a sudden new rules come into play, and several situations will arise when your most tattered jeans and your most favorite t-shirt just won’t get the job done. One of these important times is presenting at or attending a scientific conference. Regardless of whether you’re heading to the meeting just to learn some new science and do some networking or whether you’re giving your own platform or poster presentation, scientific conferences are an important fixture in any young scientists’ career. It’s a time for your work to be seen by a bigger audience, to make connections that will last throughout your career, and to leave a good impression on potential future employers and collaborators. Like it or not, your attire will be part of that impression. So given the importance of conferences, what’s the best way to dress for success? What’s your style? I’m not going to write this post as a go-to style guide on How to dress yourself for a conference, but instead I’ll focus on the more important question of What’s your style?, since finding the answer to this will set you up for knowing what to pack in that suitcase of yours. Finding your style will take some time, and likely you’ve already gone through some style phases of your own. In high school and college, I didn’t really have a great sense of style, and found myself trying to figure out how I wanted to look by trying to emulate what I saw on other people or what looked nice on a store mannequin. At some point in grad school, and really not even until my post-doc, did I figure what type of clothes I liked and what looked good on me. Since then I haven’t deviated too far away from my go-to outfits, which are generally skinny jeans, fitted graphic t-shirts, and a blazer/sweater combo (since, after all, life in Northern England is generally not adept to being out in just a t-shirt). Finding my own style came down to asking myself what I wanted to convey through my clothes, and the answer was that I wanted a balance of fitted yet casual and simple yet able to be scaled up with a change of shoes or jacket. I won’t be able to tell you what exactly you should wear at a conference, but will instead I encourage you to think about what message you want to convey through your style in general. If it makes you happy and makes you feel good about yourself, then go for it! Once you figure this out, you can focus on tailoring your conference wear as simply a slightly upgraded version of your regular style. To be both comfortable and presentable throughout the conference day, think of an outfit that would be appropriate for a long day at work followed by a social event (such as getting a drink or eating out with your friends). Once you have this in mind, take the outfit up a notch in terms of professionalism. Focus on clean and simple outfits that will let you and your work shine. And while I’m all about finding your style and embracing your own sense of you through this blog, I would encourage you to not have your conference style to not be a hoodie and pair of sweatpants. While it’s important to be yourself and to be comfortable, you also want to make a good impression by showing the best side of you possible, so here’s a few tips to help you get there: These boots were made for walking, and that’s just what they’ll do. If you’ve never been to a conference, here’s the first thing you should know: conferences take a lot out on your feet. You might first think that you’ll just be sitting in presentations all day, but there’s actually quite a bit of time you’ll not be sitting down. Between walking to the conference center from your hotel and back, going between different session rooms (and if it’s a big conference, the rooms can be quite far apart), walking outside to get lunch with colleagues, and finishing off the day with poster socials and other networking events, which will likely keep you on your toes as you mingle and meet new people. As a bit of perspective, your feet will take as much of a beating at a conference as they would a whole day standing around working in a wet lab. Since your feet are important for walking, standing, and other necessary conference activities, be sure to set yourself up for success by making them (your feet) comfortable. Again the key here is to focus on getting a slight upgrade of what your go-to shoes already are, and then you’re on your way to being conference savvy while lasting the whole day without blisters or sore feet. If your go-to style is a tennis shoe or casual trainer, then a pair of leather-sided trainers can easily be a nice conference shoe option. If you love boots and heels and wear them on a regular basis, then by all means go with them for the meeting—but only if they are a pair of shoes you’d wear if you were standing all day in a non-conference setting. If they’re not, leave them at home. Girls’ shoes are notoriously devious, as we’ve recently been tricked into thinking that ballet flats are a comfortable alternative to dressing in heels for a more professional look. If you have a pair of often-worn, broken-in flats that you wear around work all the time, then by all means bring them to the meeting. If you just bought a brand-new pair that only go with your presentation outfit, you’re better off leaving at home unless you want to spend your presentation day looking for band-aids to cover up your numerous blisters. The worst thing you can do at a conference is put your feet in so much pain that you can’t be yourself or made to feel like you should go home and change instead of taking advantage of all the networking opportunities. Pants, skirts, or something in between? Unless your conference is quite literally on a tropical beach, our official Science with Style recommendation is to avoid shorts at a conference. Even if they are ‘nice shorts’ or the weather is rather hot, shorts are still nearly impossible to help you convey a professional look. Otherwise, stick to the mantra of aiming for a slightly style upgraded version of yourself. If you’re a denim jeans kind of person, then don’t feel the need to stray too far from your go-to bottoms by buying a pair of dress pants that you’ll never wear again. If you go for denim jeans, make sure to avoid trendy washes or that damaged/cut-out look and instead go with a straightforward and simple cut and color, and darker colors can even give the illusion of dress pants if you want to look a bit more formal. Girls again have a few more options for warmer weather such as skirts and dresses. If you enjoy wearing skirts and dresses and generally go for something more loose or casual fit at work, then at the conference aim for a slightly more fitted cut. Don’t feel like you need to put on a dress or skirt for a conference if you normally don’t wear them, and don’t choose an outfit solely on the fact that it’s dressy. Go for a conference outfit that you like and one that helps you feel like yourself. If you go over the top on dressing up, you’ll be more likely to stand out due to not being comfortable rather than for having great research results. Topping things off Bring shirts to a conference that are clean and simple, and as with denim try to avoid anything overly trendy in terms of washes or wording, and don’t go for any tops that weirdly cut or showing skin that doesn’t need to be shown in a professional setting. For me, the thing I like about wearing t-shirts is that they are easy to finish off with an H&M blazer or sweater, which helps tone down the casual feel of the outfit. While I have a large range of graphic design shirts, for conferences I stick to simpler ones that are focused more on good design without much text—messages should be kept to your presentations instead! If you’re looking for a dressier alternative, button-up shirts are an easy way to have more of a formal look for a presentation or meeting a future employer. Spend the time to find a dress shirt that works for you instead of grabbing the first one off the shelf, and look for one that has a good cut for your body type as well as being made of a breathable material. The last think you want to do is to get all dressed up for a talk in some fabric that’s not cut right or starts making you sweat when you’re standing at the front of a full room giving your talk. Another fact about conferences for those that haven’t attended one yet: regardless of what country, outdoor temperature, or time of the year that the meeting is in, most if not all conference centers are seemingly designed to only be a few degrees warmer than your walk-in fridge in the lab. You’ll need to keep warm even if it’s hot outside, so layers such as blazers or cardigans are an easy way to dress up an outfit while also keeping you from freezing during the platform sessions. All you need are a couple of top layers that look good with both more casual or more formal conference outfits and you’ll easily be set for a week-long conference. Accessories for success(-ories) - Bag it up. You’ll most likely get a free conference back when you pick up your registration materials. At first glance it seems perfect: just what you need for carrying around your laptop, abstract book, and free pens from the exhibition booths all week long! The only problem with this is that this same bag will also be given to the 500+ other conference attendees, which can make it easy for your stuff to get switched around for someone else’s. Save some room in your suitcase to bring one of your favorite backpacks or shoulder bags instead. That way you can carry your conference necessities (and swag) around all week in a bag that you know is comfortable, and you can also find your stuff more easily in a pile of other delegate bags when you’re leaving a busy session room. - Keep up with the times. Your conference week will be driven by scheduled talks, meetings, and social events. Keeping good time is essential, and is also an easy opportunity to upgrade your style for a conference. I’ve yet to find a nice watch that I like and still rely on my phone for the time, but if you are looking for the opportunity to wear your graduation gift from your grandparents, there’s no better time. - Kiss and make-up? As with the rest of your outfit, aim for just a slight upgrade of your current style. Don’t feel like you need to be fancy, and for girls you also don’t feel like you need to wear make-up if you usually don’t. I hope this post offers some useful insights into packing your backs for your next (or even first!) big scientific conference. Just as with hiking, there’s no right or wrong way to do your style, but there are a few suggestions that will keep your feet from getting stubbed on rocks, or rather blistered in the case of long conference days. As for me, I should start packing my own conference bag here soon, now that my favorite blazer is clean and I have my A-team t-shirts assembled and ready for the final selection. If only perfecting my platform presentation was as easy as packing for the meeting! Science with style blog review: Gretchen Rubin’s four tendencies and making better research habits4/6/2016

Some of my recurring blog themes include topics such as knowing yourself, your working style, and your strengths and weaknesses. By knowing yourself and your tendencies, you can better figure out how to get yourself out of ruts, how to ask for help, or how to make it through a difficult situation in the lab or in the office. As part of my interest in scientific ‘self-help’, I love reading about personality assessments and combing through the theories about my own or my colleagues’ ‘types’. I use the information to think about how to communicate with other people better and also how to recognize my own shortfalls and to work to correct them.

My mother and I share the same interest in observing people and their personalities. Recently she talked to me about Gretchen Rubin’s four tendencies, a personality test that distinguishes people by the way respond to internal and external expectations. I enjoyed the simple and clear presentation, and, while I was initially skeptical of its applicability (probably due to the type of tendency I fall into), I feel it’s relevant for understanding how we work in the lab and in a research setting. You can read all about the theory behind Rubin’s tendencies on her website, but in a nutshell a person’s tendency boils down to how he or she follows instructions. In her book ‘Better than Before’, Rubin focuses on applying this theory towards changing habits, whether it be to exercise three times a week or to call your mom more often so you can discuss your entire family’s Rubin tendency distribution. It’s probably not initially clear what relevance this personality test could have in your scientific career, but as with most jobs, you spend a good portion of your day handling a lot of instructions: what your principal investigator wants, what your company/university wants, what you want, and at some point you’ll also be the one giving out instructions to others. At the same time that we receive information and instruction from various sources, we also make decisions on when do we decide to take breaks and how we decide which tasks to prioritize. I’ll leave the details of the theory and the typologies to Rubin to describe in detail, but let’s get some context for what these four tendencies are, how they may manifest given that you work in a research-type setting, and what the potential strengths and weaknesses are in the lab for each type. But first thing’s first: take the test. No, really, it’s crucial for the rest of this post! It’s a short questionnaire and only a few questions long. And as with any personality test: be sure to answer truthfully to yourself. Respond as you would respond in that situation, and try to really picture yourself in the setting for each question. Assuming that you have now taken the quiz and have been assigned your personality, we can discuss its implications. Rubin’s four personality types first came to be in 2013 and have now grown in detail and structure. The tendencies are also part of Rubin’s The Happiness Project, where she goes into detail of strategies for changing habits based on what types of expectations you follow the most. These descriptions come directly from her website and are referred to as either the Rubin Personality Index or the Rubin Tendencies. We like Rubin Tendencies, so we’ll stick with that one. The four tendencies are obligers, upholders, questioners, and REBELS. In the quote below, ‘rules’ also refer to instruction, or really any type of expectation. “Upholders respond to both inner and outer rules; Questioners question all rules, but can follow rules they endorse (effectively making all rules into inner rules); REBELS resist all rules; Obligers respond to outer rules but not to inner rules. - Upholders wake up and think, “What’s on the schedule and the to-do list for today?” They’re very motivated by execution, getting things accomplished. They really don’t like making mistakes, getting blamed, or failing to follow through (including doing so to themselves). - Questioners wake up and think, “What needs to get done today?” They’re very motivated by seeing good reasons for a particular course of action. They really don’t like spending time and effort on activities they don’t agree with. - REBELS wake up and think, “What do I want to do today?” They’re very motivated by a sense of freedom, of self-determination. They really don’t like being told what to do. - Obligers wake up and think, “What must I do today?” They’re very motivated by accountability. They really don’t like being reprimanded or letting others down. “ Quoted from Gretchen Rubin blog, 27 March 2013 So now that you’ve done the quiz, what do you think of this short assessment of yourself? Do you wake up every morning thinking about what your Rubin tendency says you do? You can read in more detail about your own Rubin Tendency if you’re interested. After reading the detailed reports for the four Rubin tendencies, here’s our own shortened interpretation of them: - Upholders are great doers and achievers, but may struggle if there’s no clarity or no plan. - Questioners are very internally motivated, but may run into issues if they can’t accept worthwhile direction or advice from others. - REBELS have great ambition and creativity, but may resist following direction if they don’t feel like they can do what they want on their own time. - Obligers are reliable and dependable, but may have issues with being too self-sacrificing and spend time building up others before themselves. While Rubin focuses on how types related to habits and her books show you how to create good habits based on what your type is, in this post I instead wanted to highlight some common scenarios that can come up in research and how each type might get caught up with and a potential solution/approach. Upholders: The to-do list masters who may run into progress speed bumps with things like:

What can upholders do? You’ve already got a great work ethic, now you just need to figure out how to think on your feet and think outside the box:

Questioners: Good at critically evaluating everything…except sometimes themselves! Here are the issues that these constant wonderers of ‘why’ can fall into:

What can questioners do? Asking a lot of questions is a good tendency in science, as long as that critical evaluation is evenly distributed and fair. To give yourself a fair assessment, work on the following:

REBELS: Will challenge ideas and reach for the skies…but may have a hard time getting there if they don’t listen to others. Here’s what trouble REBELS can run into in the lab:

What can REBELS do? It may sound like a hard sell to be a good REBEL scientist at first, but one of the things that makes rebels great is that they go against the grain-think of all the great paradigm shifts in science that came from looking at the status quo and saying ‘no’! Nonetheless, you do have to play by the book, at least a little bit:

Obligers: You’re everyone’s favorite, most helpful lab mate, but your own work will go un-worked on if you have a job to do for someone else. Here are some other situations that an obliger may run into:

What can obligers do? It’s hard to put yourself first, so here’s some tips on how you can look at your internal obligations with an external focus:

The thing I like about the Rubin tendencies in the context of research is that it highlights the need for teamwork. There is no one perfect personality type for academic research: we all have to challenge currently held perceptions, knowledge, and ideas, but also have to know when to follow the rules and respect the knowledge already in play. We have to strike a balance between working towards our own goals and recognizing the value of working with others. The key with integrating the tendencies in your own research career is first to recognize which tendency you follow the most and to work towards ensuring that you stay on task for your own career goals. Additional life hack: find friends and collaborators who exhibit different tendencies than you have to balance out the scales. Whoever said that psycho-analyzing your friends and co-workers couldn't be fun or useful!!

The great philosopher Led Zeppelin has always has a way with words:

In the days of my youth, I was told what it means to do science, Now I've got a degree, I've tried to learn important facts the best I can. Memorized and synthesized and learned the entire Krebbs cycle too, [Chorus:] Good meetings, Bad meetings, we know you’ve had your share; When my attention span wanes after 3 hours, Do I really still need to care? As a career scientist in the modern era, you have numerous jobs besides being a scientist: you’re a project leader, teacher, motivator, finance manager, accountant, PR manager, public speaker, fundraiser, and personal secretary. In an ideal world, you could concentrate on doing your science, writing papers on your own at your own pace, and spending most of your day in your office or in the lab thinking about new ideas and bringing them to life. In reality, you have to manage your own tasks while working with others on large multi-organization projects, engage with collaborators to write new grant proposals, and be ready to work as a team to get something finished that would take you ages to do on your own. While we know the type of science needs to be done to make progress in our understanding of the universe, it’s not always clear how to do the necessary thing that will enable scientist to do this great work. One of the essentials is learning how to work in groups, and part of that is how to lead productive group work. Unfortunately we all know too well what a painful, unproductive meeting feels like: the project meetings where one person drones on endlessly, a conference call that was scheduled to last an hour but has already gone for an hour and a half with still three agenda items to go, or a club at your University that meets every month and always talk about the same thing with nothing getting done. It may seem more productive (and enjoyable) to avoid meetings altogether, but disengaging from work groups will put you at a huge disadvantage. Part of being a scientist means collaborating, and part of collaborating means you engage in group discussions. If you avoid them now but then end up in a project leadership position down the line in your career, will you know how to make an agenda? If you miss out on key discussions with a group you’re involved in, will you know how to make the group’s activities more impactful for both the group and your own career? If you skip out on face-to-face meetings on your project, will you know how to respond in a work setting when your boss turns to you in a group and asks ‘So, how does your project fit in with our 10-year plan?’ Learning how to be involved in group activities, as well as how to deal with groups that may not be going in an ideal direction, can set you up for success in your future career. Knowing how to lead a small group of people effectively and efficiently is a huge skill for any type of research position with leadership or management responsibilities. Honing the art of finishing a conference call on time, while still covering all the key discussion points and doling out action items, can help lead you to more papers and more grants. Regardless of what sector you end up working in or at what stage of your career you find yourself, learning how to manage and work in groups can bolster your own project’s productivity—setting you up for future success on a wider scale. What makes a group or meeting effective? - Having an overall goal. Above everything else in this list, a clear and well-understood goal is the key to making any group effective and to make any meeting productive. Whether it’s a conference call about a draft manuscript or a graduate student society group at your university, there should be an understanding of the goals and objectives of your group’s activities. The goal doesn’t have to be complicated-it can be “To write a paper by May 2017” or “To organize events for graduate students at our University on a regular basis”, but doing anything without a goal in mind can lead to tangential discussions and unproductive meetings. Having a goal doesn’t mean everyone in the group will simultaneously know the process to achieve the goal. If the goal is simple then the process is easily understood (e.g., if the goal is to write a paper then you get there by writing the damn paper), but for more nebulous events like lab meetings the goal or process can be unclear. Are you there to give an update to your PI on what you did each week? Or maybe to summarize a month’s worth of findings as part of a longer presentation? Or does your PI simply feel that your group ‘needs’ to have a lab meeting and you end up suffering each week through two hours of the same rambling comments as the week before? Identifying the overall goal and how to get there can alleviate the need for long, drawn-out discussions or just meeting ‘because we should’. - Clear expectations of who is doing what task. As with having a goal and knowing how to get there, an important part of group work is actually doing the things you talked about in the meeting. It’s great to generate new ideas, but leaving these ideas on the table without a clear picture of who will take up what charges can lead to you coming around to the same table again in a month’s time with nothing new to discuss. In a formal meeting setting these are usually drawn up as ‘action items’, but if you are feeling less formal you can always just refer to them as a to do list. Drawing up this to do list is usually the job of the group leader, but if your meeting is more informal you can help in productivity by offering to keep track of action items and who is responsible for which task. You can then link these tasks back to the goals of the group and see if what the tasks contribute to achieving the initial goal. If not, then the task can be considered less of a priority. - An engaging leader who listens and directs. Leaders have to take charge and direct, but they should also be good listeners and people who get other members of the group to engage. At the same time, they should be people who keep tangential discussions to a minimum and will change or redirect the topic as needed. Depending on the type of group, this could be either an elected or an informal position, and most of the time you won’t get to pick who this person is. If you feel like a group you’re working with is lacking in this type of leader and also doesn’t have a formal set-up for who directs the meeting, feel free to talk to the group members and give it a try. Offer to lead a conference call or a lab meeting and see how it feels to direct conversations and discussions. At some point you’ll have to do this kind of work anyways, so ‘practicing’ in a less make-or-break setting can help when you do have to take a lead on a project that directly belongs to you. - Deadlines that aren’t arbitrary but can still be flexible (to a point). No one likes deadlines, but they are a part of working life and should be ascribed to whenever possible. That being said, a good way to motivate your group is to have deadlines that mean something. Instead of ‘Finish your part of the proposal this in by Friday because we need to finish it,’ spin it as ‘Please get this to me by Friday so we can send the proposal to the University Organizations committee for consideration next week’. This shows the group that what you’re doing has a reason for needing to be done when it should be done, and isn’t due to your own personal whims or schedule. There will always be a task or two that falls behind schedule, whether someone forgot about what they were supposed to do or had an unexpected trip or other deadline turn up. If you’re active in the group, be ready to help out and get other tasks done that really need to be done, and if someone crucial is being slow then be ready to remind them a few more times before handing off the task to someone else. - Participation from all the players, not just the leader or a select few. This is where both you, as a participant, and the leader of the group come into play. A good leader should not only listen, direct, but also ask for feedback and participation from other group members. People may not always volunteer opinions or offer to help with a task. If you know someone has something good to say or might offer some support for a task that needs to be done, asking that person directly is a good way to get them involved. That way it’s not just the outgoing ones that get involved with the work, but the quieter ones that may not want to speak up in a group setting. You can also follow up with them after a face-to-face meeting by email, where less outgoing people might be more comfortable expressing themselves. - Celebrate successes and learn from mistakes. As with the rest of your scientific career, the success of groups you are involved with will be a mixed bag: some things will work fantastically, and others will fail miserably. A successful group is one that takes the good with the bad, and one that celebrates and thanks its participants for achieving good work, and looks back and tries to learn from the things that didn’t work out. So now that you’ve got this list, every meeting you go to will be a good one, right? Right? Unfortunately bad meetings are a part of life, no matter what type of job you have. But you can make bad meetings better by putting this list to practice: by encouraging your group members to have goals, to think about leadership styles and engaging all members, and to help out when you can in getting ideas off the ground or moving on from a topic that’s been droned about. Even group members who aren’t leaders or organizers can have a huge impact on productivity, and actively participating and getting others engaged can help you get remembered by the folks in charge. And with that we’ll close off our post with The Zep, who more than anyone knows you’ve had your share of good and bad. But yes, you do still have to care, and by caring you can help take a meeting from bad to good. Just think of all the times* you could listen to Stairway to Heaven if you help bring a meeting to a close in a reasonable amount of time and get an extra 30 minutes in your day? *Approximately 3.75

We’re taking a break for the time being from our research entourage series, with the final installment to be delivered next week, due to a slight change in how I’ve spent my spare time writing. I’ve been sending off a flurry of job applications, with more to be done in the following days, due to some uncertainty in my project’s contract extension. The year started off with positive news, and a draft of the contract even made it to the University to be signed by our legal team. But with industry budgets being as they are it was soon on the 2016 budget chopping block, and my fate went from certain to unknown (cue dramatic music!!). While I’m still duly optimistic about my project’s fate, I’ve also recognized the risk of my current post-doc project money ending in June and having nowhere to go but to begin my blues guitar career at the Liverpool Docks.

Initially I felt really uncertain and nervous about my prospects and a bit lost at the thought of looking for a job when I thought I would have another year until I needed to start. It was at this low point that I followed my husband’s recommendation and started reading ‘The Alchemist,’ the story of a young shepherd from Spain who sets out on a quest to find his treasure, buried in the pyramids of Egypt. Along the way things range from going really great to sucking pretty badly, with everything from successfully evading desert henchmen to getting all of his money stolen the first day he arrives in a city. In the book, there is a lot of talk of finding your Personal Legend, with it frequently mentioned that ‘when you work for your Personal Legend, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.’ I thought about the shepherd these past few weeks, a person brave enough to leave his happy home and venture forth for his dream. I pondered if by changing my mindset at this potential juncture in my life that looking for a new job could feel the same way. While I am still nervous about what happens next, I am trying on a new attitude for my job hunt: envisioning the search as an opportunity to think about what I want my career to look like next and what I can do to get there. While working out exactly what my Personal Legend is will probably take a while, in thinking about my current career and where I want it to go in the future, I’ve realized that I like research, but don’t always love it. I enjoy doing good work and in working hard, I enjoy making connections, and I enjoy talking about research and hearing other people get excited about my work or their own. In looking back on the moments of my own career that stood out the most, it wasn’t the number of publications or how many people attended my conference talks: it was bringing ideas and findings together to tell a story, and it was listening to other people’s excitement and enthusiasm about science that kept me at it. For this reason I’ve decided not only to look for post-docs or research-oriented positions (as I still enjoy what I do and want to keep doing it while I can), but also to keep an open mind and send in a letter (or seven) for science outreach, public engagement, and science writing positions as well. It might be a tough sell in terms of my experience vs what other more traditional candidates bring to the table, but I figured it’s worth a go, and might even lead me to my own bit of treasure at the end of the desert (someday, at least!). And while it may seem like a long-shot at the moment, I’m not the first person with a Ph.D. who’s thought about doing something else, so if other people can do it then so can you (and I)! As I go through my own rounds of applications and cover letters, and trying to keep myself motivated and not become overly pessimistic about the situation, I’ve come up with a few talking points on how to get through the job application process. I’ll refer to them as talking points instead of tips, since ‘tips’ would imply previous success, which in my case has still yet to be determined: - Never stop looking but keep your focus. I have a favorite couple of job websites that I peruse on a bi-weekly basis; if you're in the UK and looking to stay in academia or a university setting, then jobs.ac.uk is a great place to start. If you have a university or area in mind and are looking for academic prospects you can also check directly on a university’s website. I have a tendency to just start opening tabs on everything that sounds vaguely promising, but then make it an effort to select the best few and make a note of when the application is due so I don’t miss the deadline. It keeps me aware of the jobs that are out there, with new ones coming in to my view a weekly basis, but in the end I don’t apply for all of them and instead focus on ones that seem the most interesting or the best match to my profile. - Don’t be afraid to go outside your comfort zone, or qualifications. You can easily tell if you’re not qualified for a position if they name an essential degree or X number of years of experience that you don’t have, but for a lot of entry-level type of work, the requirements are a bit more vague. Even if you feel that your application would be a bit of a stretch—for example, maybe the position is in the health sciences and your degree was in Ecology—don’t be afraid to go for it anyways. You can highlight the other parts of your profile that are a strong match and how your unique skillset is a good fit for the role, even if you’re not a 100% match on paper. The good news is that if you over-extend yourself, it’s not going to come back and bite you. You won’t get in trouble or have to pay any application fees if you apply for a job you don’t get. And if you never applied for the job in the first place, you definitely wouldn’t have had a chance. So the odds are in your favor to just go for it and see what happens! - Read the post in detail and learn about the company/organization. You only get a resume/CV and a cover letter to get your foot in the door with an interview, so how you set things up and the words you use really matter. If the position calls for a specific technical skillset, then make sure that’s clear and upfront on your CV. If the job is looking for someone with managerial or leadership experience, put any work you’ve done in extracurricular leadership, volunteer activities, or certifications/courses that fit the role. If the job description mentions that they need someone who’s good at ‘strategic planning,’ then bring this phrase into your cover letter with a short description of how it applies to you. Having the key sections or phrases laid out for the application reviewer to see easily can give you a leg up when it comes to making the first cut. - Have someone critique your letter and resume, and if possible use a different person each time. Before you send your carefully crafted letter and CV, have a friend or colleague take a look at it. And by ‘friend’ we don’t mean your friend who tells you that everything you do is full of sunshine and rainbows. In this situation, you need a friend who will be honest in telling you if the way you phrase something doesn’t make sense, if your letter is too long/too short, if things need rearranging, etc. Having a friend with a critical eye at this stage can help you beat the more severe critics later on down the line. If possible, for each letter try to get two people to read it over, as having another perspective can help you find things that aren’t clear or readable, and your second reader may find something that the first one missed. - You’ll get a lot of ‘We regret to inform you’ replies…and that’s OK! Even when it’s a job you weren’t really that excited about, getting the email that you didn’t even make it to the interview stage will deal a small blow to your motivation and confidence. Unfortunately, part of the process of applying for jobs involves not getting a lot of the jobs, and being constantly rejected is not something that any of us enjoys. It is frustrating, but it’s just part of the process. I recently heard that a friend of mine from grad school who recently became a professor went through 17 unsuccessful job applications before he got his current, tenure-track job. I’m sure none of those 17 rejections was fun or desirable, but in the end he got to somewhere good and likely learned a lot about the process along the way. - Get feedback if you can. Whether it’s an application that didn’t get through the interview stage or you made it to the interview but didn’t get the position, ask for feedback on yourself and your application. You might not get feedback every time, but when you do, the information can be helpful for figuring out what you need to address or bring forward more in a future application. Just like with the amount of rejection you’ll likely encounter, it will be hard to read critiques on you and your work, so try to look at the words as a means to move forward and to grow from the experience as a whole. - If you have a type of job in mind, do some informal interviews to get some behind-the-scenes info. Sometimes the key to getting into a new field or area of research is to get info from someone behind the front lines. Especially if you have an idea of where you’d like to end up, find a mentor from your own network or cold call someone from your university/city that has the job you’d like to have someday. Set up an informational interview with them, where you can ask questions about what their job is like, how they got there, and what resume reviewers in the field are looking for as they go through pile of job applications. It won’t guarantee you a position anywhere, but having some inside information on how things work and what’s important in the field can help you have a leg up when it comes to structuring your application materials. - Don’t forget to talk to your references beforehand. Your personal references likely won’t be contacted until later in the application review process, but before you click ‘submit’ make sure to ask them if they can be a reference and let them know the type of jobs you’re applying for. There’s not a lot of things more embarrassing then having a prospective employer call a personal reference and surprise them with news of your job searches and questions about you and your working style. With this week’s shorter post to set you on your way, I’m back to juggling job applications while doing what I need for my current job, and looking forward to the day when I can have my writing brain back in full again. Until then, I’ll keep on putting myself out there, learning from applications that didn’t make the cut, and staying optimistic (as much as possible) in the face of what I’ll refer to as a life opportunity instead of a career challenge! If you’re interested in additional discussions or have a question about career transitions, you can join the #withaPhD chat moderated by Jennifer Polk on Monday Feb 22nd from noon-1pm EST on the topic “Surprising jobs and careers.”

I've been meaning to write a blog post since the meeting kicked off on Monday, but as conferences always go there's always someone to talk to or some meeting to listen in on or a talk to attend. I'm taking advantage of a short break between coffee socializing and talking to students and exhibitors about the next SETAC YES meeting to write down some thoughts and perspectives on this conference.

This is my 6th time attending the SETAC North America meeting, and even as an early career researcher I'm always overwhelmed with catching up with people I knew from before while also making new contacts. It's great to be back as something of a scientific family reunion at this year's meeting in the clean and contemporary capital of Utah. Salt Lake City has been a great venue for this event and for my return back to the US of A after a year away, and a good opportunity to wear my autumn boots on this chilly autumn day! While I've been busy this week I've managed to come up with a few thoughts and suggestions to help make the best of those fast-paced and exhausting conference days: - Be comfortable. I yet again made the mistake of wearing heels on the first day of the meeting. I followed up the rest of the meeting wearing my favorite broken-in Lacoste black trainers, and while I may have looked more casual I felt more comfortable and more like myself. When you feel comfortable you can act more like yourself and let the more important things shine through, like your passion for your research or your presentation skills. We tend not to wear conference clothes all of the time, with shoes not broken in and dress pants we haven't worn in a year. Instead of just dressing up, focus on embracing your style while still conveying a professional look, attitude, and how you carry yourself. And if you can stand and talk to a new contact without shifting awkwardly in shoes giving you a blister, you can make the focus of the conversationmore on you and your ideas and less on what you're wearing. - Let ideas happen. I spoke on Monday to Namrata Sengupta from Clemson about the Clemson What's in our Waters (WOW) project, which I'll feature in a future blog post talking about outreach projects at different universities. This idea first came about over drinks at a previous SETAC meeting. It wasn't from a formal sit-down brainstorming session but just came about while sitting around with friends and colleagues talking about what would be fun, useful, and engaging for undergrads. At conferences we all get busy thinking about our own presentations, project meetings, and talks we have to go to, so be sure to leave time for creative endeavors and new ideas to take form, which often times don't take place in a board room but at a pub or over coffee with friends. - If you're at a loss for words, ask where someone is from. I love doing this because it can always lead to a story or a shared experience. Maybe you've been on a trip to where someone grew up or you happened to go to nearby universities for undergrad. It's interesting to see where people go and where they came from throughout their careers, and it's an easy conversation started since everyone you meet is always from somewhere. One exhibitor even made a word association game out of it, asking people what the first thing they thought of when they heard 'Texas'. It was a bit more boring to do that the opposite way for me and ask people what they thought of about Nebraska. Yes, it is flat and yes, we have corn. - Take notes! I'm in a slight crisis at having lost my original program book, after I wrote down some ideas and follow-up tasks during an organizational meeting. Now I thankfully have my trusty green idea notebook back at hand and have been jotting down impressions and ideas from this meeting along the way, without needing to rely on the intermittent wifi connections. You'll meet so many people and hear so many ideas, so write them down before you forget them! I also write down a couple of words about someone if I take a business card, whether it's what we talked about or what I wanted out of a follow-up, just so I don't end up with a pile of names and affiliations after a long week of talks and meetings. - Minimize your screen time. The hardest part about being a blogger at a meeting is that I don't want to sit by myself and blog! There are so many colleagues and new people to talk to that I hate the thought of isolating myself to write. For me, writing is a way to relax a bit and recharge after a lot of social and professional interactions, so forcing myself to think and write during a break in the meeting was a good exercise. It can be tempting, especially for us introverts, to want to spend too much time on your phone or computer or to make excuses that you need to work on something. While there are emails that need answering and presentations to practice, be sure to focus on using your time for personal interactions. And they don't always have to be formal-great ideas and connections come from coffee with new colleagues or jokes at a poster social. Now with the poster social starting I should get off my laptop and back into the social universe. Good luck to those of you finishing off the SETAC meeting and for anyone with an upcoming conference,whether its a first-time meeting or sixth-time meeting! Tomorrow is my conference presentation so I'll tie up the lose ends of the post I made about making my conference presentation based on the five easy steps for making a presentation. So stay tuned for an upcoming post on how it went and how I used the five steps to make the best possible presentation. And now, time for beer and networking! Playing nicely with others: When success in science hinges on more than just what you know10/21/2015

I think it’s safe to say that most of us have benefited from Jorge Cham’s PhD comic series even if our research and general productivity hasn’t. It’s easy to spend an afternoon scrolling through the comic archive and thinking Yep, been there, done that, seen that. His all-too-real depictions of situations strike a chord with many aspects of life working in a research laboratory. One of his recent comics resonated for me on two separate occasions. Originally posted on Sept 4th, I think I actually laughed out loud when I first saw this one:

I’ve seen far too many similar warnings posted in the lab, office, or shared kitchen, reminding us all that equipment belongs to one person and one person ONLY, or reminders that ‘your mother doesn’t work here, so clean up after yourself’. I’ve received a fair amount of scorn from lab managers and senior grad students or post-docs for using a piece of equipment without signing the log book about the 2 minutes I spend on the machine. I have borne witness to a wide array of emails on department and even college-wide email lists chastising someone for a minor infraction or something that could have been handled more maturely and directly (instead of involving the entire department). While Jorge Cham might lead us to believe in his comic that grad school isn’t kindergarden anymore, sometimes I feel like we’re back in elementary school all over again, but this time with the mantra of ‘sharing is good’ replaced by messages on snarky post-it notes indicating that if someone doesn’t clean up their mess they’ll be promptly sent to the 3rd circle of hell.

While it’s easy to laugh about situations like this, these attitudes in academia, and in scientific research as a whole, can hold us back from making progress in our work. I was reminded of this comic a second time last week when I found this article “How the modern work place has become more like preschool”. The article is not comic material but instead discusses the reasons for the increase in the number of jobs requiring interpersonal skills. While the loss of many ‘unskilled’ jobs may not be of concern to someone holding or working toward a PhD, in today’s competitive workforce there are WAY more PhDs than ever before. The traditional place of employment, academia, can’t make homes for all of us, and those that are trying to get into any sort of permanent position will be competing against a long list of other applicants, some with more publications, more grants, or more relevant experience. Interpersonal skills and how you work with others in a team setting can make the difference in you landing your dream job versus you landing just any job. The Nobel-prize winning economist James Heckman wrote a paper on the relationship between cognitive skills (e.g., intelligence as measured by aptitude tests) and non-cognitive skills (e.g., motivation, perseverance, self-control, etc.) and how these two factors correlated to endpoints related to success in life: getting a 4-year degree, how much money you make, etc. While there are quite a few conclusions that can be drawn from the results, depicted as surface plots over the two-dimensions of cognitive and non-cognitive skills (scroll to the end of the paper), the quick take-home message is that it takes more than just being smart to succeed. It’s a combination of how smart you are as well as how well you make it through life’s challenges and how you interact with teachers and peers. There is a strong need in today’s workforce, and in science especially, for people who can empathize, see others emotions, and respond to them appropriately. The New York Times article goes on to describe the reason for its title: “Children move from art projects to science experiments to the playground in small groups, and their most important skills are sharing and negotiating with others. But that soon ends, replaced by lecture-style teaching of hard skills, with less peer interaction. Work, meanwhile, has become more like preschool.” This is an all-too-true situation for those of us in the scientific fields: we spend our time in high school and undergrad gaining in-depth knowledge on a topic before we graduate. Then for those of us that decide to continue our studies, the world suddenly changes: the bulk of our time is now spent in lab meetings presenting our research, learning a new protocol from a lab mate, collecting data with a collaborator, or revising papers with our advisor. While there is always a part of your research where you will work independently, the collaborative atmosphere is much more prevalent after your undergraduate studies. It’s here that the natural sciences such as biology and chemistry can learn a lot from engineering programs. A bachelor’s degree in engineering is designed with the knowledge that after graduation most engineers will work in teams on large projects. As a student, group projects may seem tedious, but they provide experience with necessary teamwork skills such as how to divide tasks based on the members’ skills and knowledge. As such, students who will end up as professional scientists could also benefit from team projects. Just like how trends in the general workforce are leaning away from hiring people that can only do manual labor tasks, scientists need to hone their teamwork and collaborative skills in order to set themselves apart from the rest of the crowd. Another section of the NYT article describes a situation that many of us have likely faced already: “Say two workers are publishing a research paper. If one excels at data analysis and the other at writing, they would be more productive and create a better product if they collaborated. But if they lack interpersonal skills, the cost of working together might be too high to make the partnership productive.” This is an example of something that happens all too often in academia. If people know that you’re a genius at what you do but know that you can’t be bothered to sit in a room with other people and work together on a problem, who do you think they’re going to hire for the project manager position or ask to help write a grant with them? As stated in the NYT article, “Cooperation, empathy and flexibility have become increasingly vital in modern-day work.” Likewise, science has become a world of collaborations: large-scale international grants, multiple PIs with teams of graduate students and post-docs, data that requires expertise from several areas of knowledge, or a complex physical infrastructure (such as the particle accelerator at CERN). Science does not work in a vacuum, especially in this day and age where so many of the questions that remain to be answered are pressing and complex. As professional scientists we need to learn how to play nicely with the rest of the class. As you build a network of collaborators, you’ll find that this will be much easier if you earn people’s respect for who you are both as a scientist and as a person. While non-cognitive skills and ‘politeness’ lessons may not have been covered since your time in kindergarten, you will spend your entire life outside the classroom being evaluated on this skillset. It’s your responsibility to be aware of how you work with others and your strengths and weaknesses outside of your basic foundation of knowledge. To give some guidance, I’ve compiled a few things to keep in mind in order to help you play well with others. - Visualize any collaborative venture as a team effort. When you work in a group, look at people’s skills and expertise and think about what components each member can contribute. Keep in mind who will be timely with their efforts, who will need additional support, and who can be trusted to finish their contribution independently. - Foster an environment for sharing your research. Take ownership of your research but don’t keep it to yourself. Talk about ideas with your lab mates, your PI, as well as researchers completely outside of your research group. Seek out new perspectives on your work even if it’s not a formal collaboration by sharing insights and data with your peers and people outside your lab. - Your mother may not work in your lab, but pretend that she does. Moms tend to give good insights on how society expects us to behave. Even if you’ve been out of her house for a while, keep her recommendations in the back of your mind when it comes to how you conduct yourself (and the next three bullets are certainly mom-approved!). - Be nice to everyone. No matter what level of lab/office hierarchy, be they technicians, office staff, or administrative personnel, being friendly and cordial to people even when you don’t have to be will make your day-to-day life easier. It’s not just about being nice to your PI but to the people who will bring you deliveries, get your paperwork sorted so you can get paid, and who may or may not look past office deadlines in order to help you out. - Think before you speak, ESPECIALLY in emails. There will be a lot of tricky situations you’ll be faced with: scientists that don’t respond to emails, challenging your findings, or demanding more than was agreed on in a grant proposal. You don’t need to be snarky or defensive, and most issues can be managed politely without the need for overly strong wording. Remember that your emails can very easily get forwarded to a department head or saved in someone’s inbox, so use some thought before you send them! - Pay no mind to jerks. You will run into people that you won’t like, ones who won’t work well as a team or who will continually seem to poke you with a stick. Don’t worry about them, and as your teacher or mom said: mind your own business, at least when it comes to letting people interfere with your work and your mood. Do your best to try to establish a professional relationship as needed, and if that person is truly caustic then find other teammates to work more with, and be comforted by the fact that they’ll likely run into later issues with finding collaborators and colleagues in their own careers. Academia can feel like a ‘don’t touch this it’s mine’ kind of world, where the good guys just can’t win. There will inevitably be people that make messes or that won’t be nice to you. How can you set yourself apart from this preschool mentality? By setting an example through your courtesy and kindness. Focus on establishing a positive attitude for teamwork and collaboration, and work on the transition from a mindset of ‘don’t touch this it’s mine’ to ‘it’s nice to make friends!’ Your research now as well as your career in the future will be better off for it!

“Network, network, network!” Networking is often touted as the most important thing that graduate students and young researchers should do, even early in their careers. While it’s easy for people to say over and over again how important it is and to generally understand its importance for professional development, what’s not as clear is how networking in scientific research actually works, and how you should go about networking effectively.

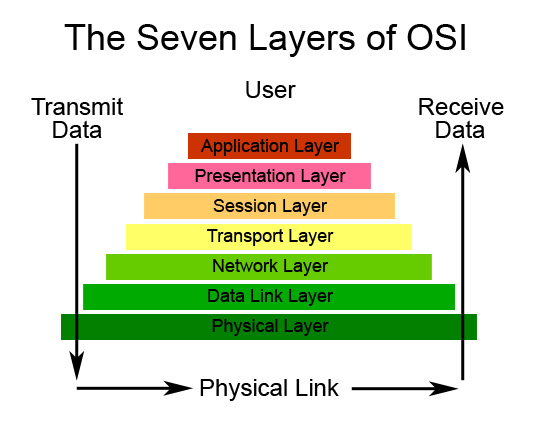

How exactly do I network? is a pressing question for students putting together the final touches on their dissertation and for post-docs and entry-level researchers who are running short of days on their contract. The elusive nature of networking can become readily apparent while attending a conference at during one of these crucial times, seeking out potential employers and setting yourself up for the next stage of your career while navigating through the busy crowds at poster socials. While some people seem to be natural at attracting collaborators and colleagues, for other it’s not as easy. For most of us, collaborators and potential employers won’t just appear from thin air, and networking is not always something that comes naturally, especially for those of us that prefer to keep to ourselves or who feel more out of place when interacting with groups of people (e.g. introverts, myself included!). Before we think further on how to network, we should first think about what networking is. Instead of rushing off to Webster, though, let’s turn to something that’s been pretty successful with its networking, by definition: the Internet. In addition to being many a source of most of the information we consume each day, with an array of activities ranging from productivity to procrastination, the Internet is also the perfect model for professional networking. The infrastructure used by telecommunication systems are designed with communication in mind, with the end goal of making purposeful connections between people and places. As nerdy as it may sound, we can actually use the infrastructure of Open Systems Interconnection models (OSI; more nerdy stuff here) to get a better picture of what networking is, and give us a road map of how we can actually go about doing this important yet somewhat nebulous professional task.

1. Physical layer