“When it rains it pours” is not just the motto for Morton’s salt, it’s also a good analogy for a researcher’s to do list. More often than not, it feels like deadlines all come at once. But working in an academic research environment doesn’t have the same kind of pressures that a traditional office setting does. Researchers have an immense pressure to get things done, but when there’s no project deadline or a looming submission deadline, there really isn’t a solid reason that something has to get done at that moment in time. Deadlines are the way that most companies stay working on schedule, but in the world of academic research, how do we get things done?

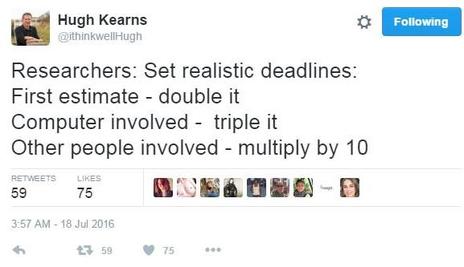

Let’s start with a typical example of research output: a manuscript. Unless you’re sending an article to be part of a special issue or when you’re doing a resubmission, you probably won’t have a hard-and-fast-deadline for submitting a manuscript: you can send in a paper any day, be it next week, next month, or next year. Academia then becomes this blend of feeling like we need to get something done but accompanied by a deadline that’s more fluid, depending on when you feel like you need to get it done, or when your boss or PI wants you to finish it. But even amidst the pressures your PI might put you under, the fact remains that you can still submit your manuscript at any given time. And while you might have a PI that gives some hard deadlines on projects, papers, or analyses such as “Have this done by your next committee meeting”, it may not come in the form of “Have this done by midnight on October 3rd,” as you would have had for classroom assignments and homework. And that’s not the only place that academic deadlines show their more fluid side. I found myself laughing out loud by this recent tweet by @ithinkwellHugh: If you’re still at the stage in your career where you’re working more independently, the last point might seem a bit daunting. “Ten times? Really? Surely that’s an exaggeration.” But anyone that’s worked on a large group project before knows that this multiplier factor is spot-on. Collaborating with other researchers on big group projects, projects that might not have a solid deliverable deadline akin to submitting a manuscript, means that the pace of the work is inevitably much, much slower. This initially might be a welcome pace, especially if this work not crucial to your out research output, but after weeks or months of inactivity from all parties due to a lack of central oversight, someone will realize that something needs to get done and it needs to be finished right now. And depending on your specific role in the project, the bulk of this last-minute, needs-to-be-done work could easily end up falling on you. The way that academic research and collaborations work is not likely to change anytime soon, but it doesn’t mean that all your work has to pour down on you all at once. You can develop a working strategy that helps you set yourself apart by learning how to become your own boss and track your own productivity. As independent researchers in the making, learning how to be in charge of setting your own deadlines and keeping other collaborators and colleagues working within a deadline-less world is an essential task. Here are a few ways to work towards a more productive working schedule even amidst a deadline-less working environment: Figure out your tendency. We reviewed Gretchen Rubin’s four tendencies in a previous post, and if you haven’t already checked out the quiz and read about the typologies, be sure to give her books and website a look. Especially if you struggle with stress at work or with staying on task, Rubin’s approaches for developing productive habits and working styles that align with each tendency are a great starting point. It’s much easier to figure out what strategies will and won’t for you in a research environment if you can better understand how you work and how you relate to expectations and deadlines, and you can use these approaches to make sure you don’t over-work yourself or under-deliver on your research outputs. Be realistic. For each of your big-picture, major tasks that you need to finish for your project, think in detail about all the components. If it’s lab work, how much prep time will you need for a single experiment? If you’ve done something similar before or are scaling up a smaller part of your work, how long exactly did it take and was there any troubleshooting involved? If it’s computer-based, how much of the work can be streamlined and how much time will it take for programming, formatting data, etc? It’s easy in research to trivialize tasks, especially ones we do on a regular basis, only to realize while doing something on a larger scale or on a short deadline how long it actually takes to double the number of replicates or to run code on a dataset that’s ten times the size. As with Hugh’s tweeted recommendations, give yourself some breathing room, especially if it’s something you never did before. Once you have an estimate that will give yourself a little bit of breathing room, double the time, since a dropped test tube or a computer freezing up can still set you back. Setting yourself up for success can be linked in part to knowing what’s feasible in a given amount of time, which can help reduce your stress levels by knowing what needs to get done but at the same time taking a breather in knowing that it will get done. Make daily and weekly goals. It’s easy to get stressed while thinking solely in the long-term months and years of all the work you have to do. Instead, put more of your focus on what you need to do that day and that week, and keep your big picture to-do’s in you peripheral vision. Given your realistic timelines, what should you work on today? What lab or computer work can you fit in together to give yourself a break from one or the other while still staying productive? If you keep your appointments and meetings in an online calendar, also include a place where you can list your daily to do’s, and check things off as you finish them. If you still enjoy keeping an analog version of a day planner and to do lists, write down what you need to get done that day and that week and check them off when each one is done. Doing this also helps you feel like you achieved something, especially if there may not be a ‘real’ deadline involved with the daily tasks or if the big picture to do, like publishing a paper, is a bit further ahead in the future. On a weekly level, have a few bigger picture goals in mind that are distinct from your day-to-day tasks and that can help you further your longer-term goals. Are you working on a manuscript and need to sort out your outlines or figures? Do you want to get in touch with a potential collaborator about an idea you have but always seem to forget to do it? Have these written off to the side of your daily to-do’s, and when you find yourself with 20-30 minutes to kill, take a look at your weekly goals and see what can be done in that period of time. You may not get everything done that you set out to do for your weekly goals, but keeping some bigger picture to do’s in your periphery can help you from being blindsided by big tasks like submitting a paper or writing a grant proposal. Recognize when you’re not being productive and step back. There is such a thing as trying too hard: sometimes when trying to get or stay motivated or focused, we just end up worn out and opening yet another tab on the internet (or, nowadays, checking our phone to see if any pokémon showed up nearby). Academic guilt has a way of making you feel like you should work all the time, but this is never a good strategy. Focus on getting your daily and weekly to do’s done, and if you find that you get to the end of one task and are not quite ready to start another, take a walk around the lab or make a coffee and give yourself time to digest before jumping in feet first to the next thing on your list. In big projects, make tasks and objectives clear. The first step in successful group work is being clear on who’s doing what. Make sure that the tasks and deliverables for the project are clearly delineated, and if something belongs to you then do your best to finish that part of the project on time. If things that you’re doing hinge on what people will do after you, keep them informed of your progress and any blocks you run into. If someone has given a deadline for a project, then treat it as such, even if there may not be a company or boss who’s breathing down your neck about it. Remember that even in research, your time is money, so take the time you need to complete a task for another project and allow the project to move forward instead of making it drag on. In group work, you may end up with someone who isn’t pulling their weight on their part of the work. It’s frustrating and will more often than not make you upset, especially if you’re in charge of the project. Instead of getting mad right away, ask them what you can help with and if they need an extension due to some issues on their side. If all else fails, be ready to take over the and consider this in the planning stages of the project by budgeting in some time for the possibility of having to do the work of someone else. Not everything has to be done in research, but there’s still a lot of things that should be done. In academia and in scientific research, you set yourself apart not by doing what you’re told but by doing something more. Bosses and deadlines will always be a factor in motivating us to finish a boring task or assignment, but for a successful career in research you’ll need to develop a strategy for working and figuring out how to inspire yourself to work when no one is looking. You can’t see everything as just a list of of things you have to do but should instead see a collection of ideas that are so great that they should be done. Research is a tough gig, but it doesn’t have to feel like your life is an endless stream of tasks and deadlines. Developing your motivation and time management skillset can keep you from being bogged down by deadlines (or a lack thereof) and can keep your work progressing on a regular basis instead of having everything fall on you at once. If you’re motivated to keep pursuing a career in research, find a way to let your work be moved by your passions instead of your have-to-do’s, and then even amidst the downpours you can find some comfort in knowing that you’re doing the best you can to make the world a better place. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed