I tend to get in trouble by our lab safety officer once every two weeks for not wearing a lab coat. I always wear one when working with some dangerous or caustic chemicals, but most of my time spent in a molecular biology lab isn’t hazardous to my health. The main reason that I don’t like to wear a lab coat when it’s not necessary is maybe an unusual one: I don’t want to look like a scientist. Even as a researcher who’s been working in a lab for the past 8 years, I don’t want to fit the stereotype of what a scientist looks like or acts like. But what is the stereotype of a scientist? How do they look and, most importantly, how do they act?

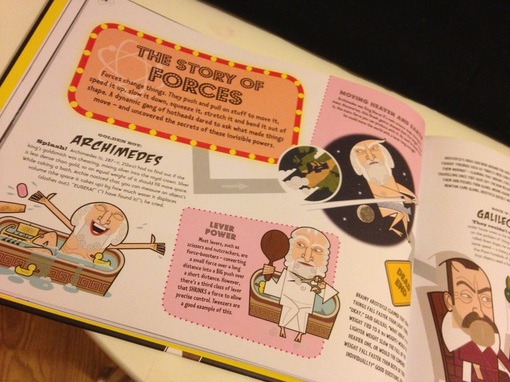

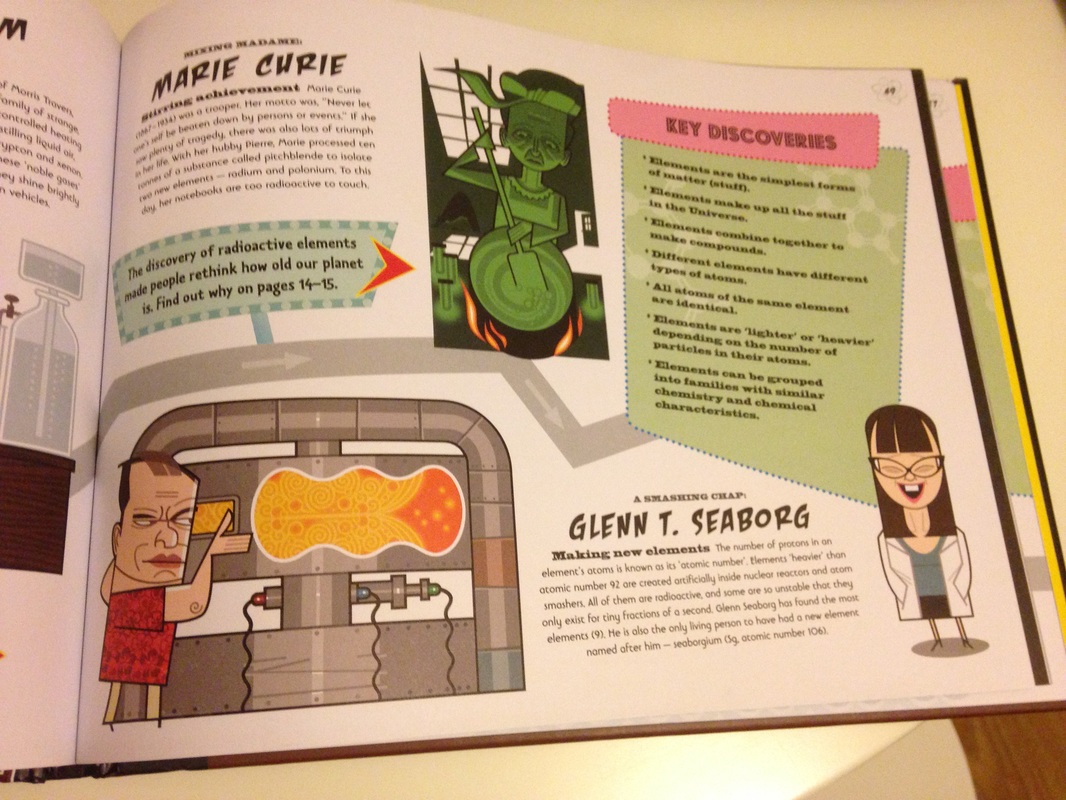

During this summer of lab work, writing, and tweeting, I’ve also been thinking about the ‘big gap’ in science, the gap between what the public thinks of what we do versus our actual research. PhD comics author Jorge Cham does a great job talking about this gap in his TEDxUCLA talk. Cham gives an example of good science communication in a collaborative project to develop a cartoon and video about the Higgs Boson. He makes note that this approach to sharing science took a lot of initiative from the scientists themselves, and it didn’t follow the traditional way of how science is shared with the broader community. Cham also comments on how shows like Big Bang theory portray researchers as eccentric and socially inept, which paints an inaccurate picture of scientists and can make the job seem unattractive to young students who don’t consider themselves geniuses or ‘nerds.’ While I do enjoy Sheldon’s banter on Big Bang Theory (because we all know someone like Sheldon in our group of colleagues or friends), I wonder if there’s a better way to talk about who scientists are and what they do. These wonderings led me to buy the children’s book, Rebel scientists, last week from Amazon. Rebels play a prominent role in modern-day storytelling: whether it’s Star Wars, Hunger Games, Braveheart, the Matrix, or the French and American revolutions, we all love to cheer for the rebels and the underdogs, be they real or fictional. But can scientists really be a part of this adjective? Dan Green’s book was one of the winners of the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize for this year. The illustrations, done by David Lyttleton, are a real treat for the eyes and help to focus the storytelling on the scientists themselves and how their work fits into the picture of our understanding of the universe. The book starts off with the timely question of “What is this thing called science?” and Dan describes it in four parts: curiosity, disagreement, discovery, and a long journey. Scientists are the ones who are curious about how the world around them works. They go against the consensus and the status quo when need be. They know that the world has a lot of mysteries that lie ahead and are driven by asking the why and how of everything and anything. Each science subject is presented as a separate chapter called “The story of ____”, with topics including the solar system, the atom, light, the elements, and genetics. Within each story, Dan starts with the early earliest thinkers and their ideas about how the world works, following through to what we know and are working on in science today. The book depicts the scientific exploration using a diagram of a road which connects discoveries together, while also provides road signs that the reader can follow to link to relevant material in other fields. The road even has the occasional dead end at an explanation of an idea that didn’t quite pan out. While the book is meant for a slightly older reader, probably for students ages 10-14, I’m amazed with the breadth of topics that are covered-and even complex subjects like quantum physics that I even had to re-read a couple of times to get the gist of the story. Below you can find a couple photos from inside the pages so you can get a sense of how the story of science and scientists are told by Dan:

I like how the book describes the Galileo’s and Einstein’s of our world: instead of calling them all geniuses or describing them as hyper-intelligent, the famous thinkers of our world are described with a wider breadth of words. ‘Rock star’, ‘radical’, rabble-rousers’, ‘sharp suited’, and ‘mavericks’ are just a few of the adjectives used. There are stories of disagreements between the biggest minds in science and how they came to a consensus about how the world works. There are stories of researchers going against the grain to pursue their ideas and delve into the mysteries that the rest of the world wasn’t able to see. At the end of the book, you can feel like the moniker of a ‘rebel scientist’ isn’t that far from the truth.

Reading this book also got me thinking about the other things that scientists do and that they are that might not come up at first though, since the thought of a 'rebel scientist' also wasn't the first to spring to mind. So what, exactly, do scientists do? We get things wrong, and that’s OK. There was more than one road in the Rebel Scientists book that lead to a dead end. But it wasn’t mentioned as a bad thing or that the person who thought the idea was stupid, it’s just a part of the process of science. Modern day science is rife with failures, experiments that go wrong, and ideas that lead to dead ends. It doesn’t mean we’re doing our job wrong, but it may not come to mind to non-scientists that as scientists we might not actually know everything. As Jorge Cham said in his talk, 95% of what makes up the universe is unknown…our world is complex and we have a lot more work to do! We are diverse, but we can do better going forward. A majority of scientists that feature prominently in history are men from Europe and North America. Some women do make an appearance, as well as a few Arabian scientists, but historically the science community hasn’t been diverse. The modern landscape is more inclusive, but we can still do better. What steps can we take in the future to ensure that everyone has the chance to contribute to the scientific community? Our job is to challenge the status quo. While scientists might be interpreted as know-it-alls or geniuses who can memorize textbooks and equations, a scientist cannot succeed simply by rout memorization of existing knowledge. Scientists have to be rebels that go against the grain, because that’s how we learn, uncover, and discover. To succeed in science, you have to do the unexpected, and being an elite know-it-all will only hold you back from uncovering the secrets that the universe has hidden from plain view. As Einstein said (and you can read more about him on Page 72 of Rebel Scientists), “Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” We do our best when we work as a team and not against each other. There are a lot of dramatic rivals highlighted in Rebel Scientists, and those of us that work in a lab will know of a few other ‘rivals’ of our advisors, collaborators, and colleagues. But what I like about this book is how it highlights the ideas that were put forth not by competing groups but by scientists working together to put the pieces of a puzzle into a single, clear picture. It’s tempting to want to blaze our own trail to fame and glory, so this book is a nice reminder that if the goal is the search for truth and understanding about the universe, working alongside others is better than working in opposition. Our world is an exciting, terrifying, and unimaginably big place. Figuring out how and why it works the way it does takes brave, enthusiastic, and rebellious minds. If people can rally behind the rebels of the science world as they do for Luke Skywalker or Katniss Everdeen, then Rebel Science will have succeeded in its mission. I hope to see more authors like Dan Green who are working to change the story of science and scientists into something more accurate and more engaging. May the force be with us and the odds ever in our favor! Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed