A new field study reports a decrease in the number of abnormal intersex fish living downstream of Kitchener, Ontario after effluent processing changes were made at the town’s wastewater treatment plant.

The article, published in the February 7th issue of Environmental Science and Technology, show how changes made at the Kitchener wastewater treatment plant lowered the number of rainbow darter with reproductive abnormalities. The plant upgrade included the addition of a nitrifying procedure, which reduced the effluent’s estrogen levels. Researchers from the University of Waterloo, the Ontario Ministry of Climate Change, and Environment Canada collected fish from the Grand River both before and after processing changes. Fish were also collected from a clean upstream site and from a site downstream of another wastewater treatment plant. This plant in Waterloo did not undergo any processing changes. Intersex fish have the reproductive tissues of both males and females. In male fish, intersex is measured as the number of egg cells in the testes. Intersex fish were first discovered in 2003 by USGS researchers in West Virginia. More studies have since found large numbers of intersex fish across North America. Exposure to hormones such as natural and synthetic estrogen is thought to be the culprit for these intersex characteristics. This study looked for the presence of intersex in a small freshwater fish species, the rainbow darter, from 2007 through 2015. Effluent processing changes were made in mid-2012. Darters collected from the clean site had low numbers of intersex (less than 20%) and the levels did not change during the study. Downstream of the Kitchener plant, as many as 100% of fish sampled were intersex before 2012. The level of intersex in these fish dropped by more than 75% by the end of 2015. The number of intersex fish was consistent at the site where there were no effluent processing changes. The estrogen levels were measured before and after plant upgrades. Estrogen levels in the Kitchener wastewater treatment plant decreased after 2012. There were also lower levels of pharmaceuticals, including ibuprofen, naproxen, and carbamazepine. Estrogen exposure isn’t limited to intersex in fish. A lake-wide study found that estrogen exposure could wipe out entire fish populations. Male fish exposed to estrogens also have lower testosterone levels and smaller testes. Treatment changes made at the Kitchener plant included nitrification of the activated sludge. This involves adding bacteria that convert ammonia to nitrogen. Previous studies showed that nitrification of sludge could reduce the amount of hormones in effluents, but this is the first study to show positive impacts on fish populations. Since rainbow darter can live up to five years, the population’s recovery over the three year period shows that intersex is not permanent. One confounding result from this study is the increase in effluent nitrogen levels. While ammonia, pharmaceuticals, and estrogen levels decreased, nitrates increased to 20 mg/L. The EPA recommends that nitrate levels in drinking water be no higher than 10 mg/L. Higher nitrogen levels promote algae overgrowth that can lead to decreases in oxygen, a process known as eutrophication. Future work at this site will need to ensure that nitrogen levels are not causing other types of environmental damage.

Every time I opened Google News last month, I hesitated with bated breath before scrolling down to the ‘Science’ section. I found myself too nervous to read whatever shocking policy changes would be waiting for me there. Even a month after the inauguration, I and many other scientists continue to wonder what the next four years will have in store. Everything related to science in the US, from basic research funding to environmental policy changes, feels like it’s at the cusp of challenging days ahead.

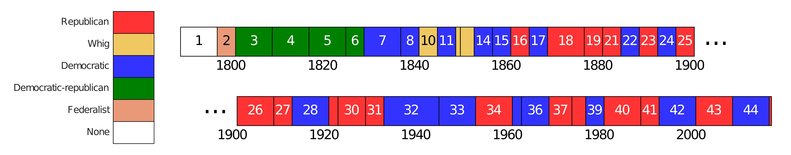

I empathize with the scientists who are silenced and for my friends and colleagues who work at government institutions, wondering how their jobs will be affected. I cheer on the rogue twitter accounts (my personal favorite being the tongue-in-cheek @MordorNPS) and I started preparing letters to the members of congress who are proposing bills that would damage the integrity of environmental regulations. But despite my empathy with the plight of government researchers and concerns for what an “alternative facts” administration will do over the next four years, I am hesitant to fully support the concept of a March for Science. I am concerned that the march will further polarize the dialogue at the interface of science and politics instead of harmonizing science communication and public outreach. In the US, scientists are overwhelmingly liberal, with 55% identifying as Democratic, 32% Independent, and only 6% as Republican. In contrast, scientific literacy, or illiteracy, is less partisan—and it’s incorrect to label one party as ‘anti-science’ over another. Scientists may tend to picture concepts such as not believing in global warming or evolution as primarily conservative viewpoints. But while 50% of conservatives surveyed said that they thought the earth was only 10,000 years old, so did 33% of liberals. Recent concerns about how Trump’s comments could potentially fuel the anti-vaccine movement didn’t mention the fact that a higher percentage of Democrats believe that vaccines are not safe. While there are extremely vocal Conservative opponents of ideas like climate change and evolution, there is a general understanding and support for the science underpinning climate change among representatives of the Republican Party. Recent news articles have highlighted bills put forth by freshmen Republican representatives to disband the US EPA, but at the same time other Republicans are working on a national carbon tax to address climate change. This effort is supported by senior Republicans who said that the “mounting evidence of climate change is growing too strong to ignore”. The difference between the two parties is not necessarily a belief in the science but in how that information is used to shape policies, and Republicans will generally advocate for less restrictive and more open market policies to approach these problems. Yes, there are vocal opponents of climate change science, and yes, the current administration has already done numerous things to warrant mistrust from scientists—but to seemingly discredit an entire party holding a majority position of the federal legislature is not a recipe for making progress. If the March for Science is going to make strides in its goal of sharing clear, non-partisan messages, it will take more than a single act of demonstration against the current administration. Looking beyond this current administration, it’s not a solid long-term strategy for scientists to be primarily aligned with only one side of the political spectrum. In American politics, one party is never in power for long, and the office of the President tends to alternate back and forth between red and blue (and the same trend follows for the House and Senate). This pendulum swing is the natural ebb and flow of political leanings in America, and makes Trump’s election win look like it was somewhat inevitable. Scientists can envision a Democratic presidential victory in 2020 as a stepping stone for progress in science. But what about future elections, from 2024 and beyond? Given the number of problems that need solid scientific solutions, from climate change to antibiotic resistance to a comet crashing into planet earth, can scientists afford to only rely on 4-8 year cycles? In our post two weeks ago, we discussed the role that Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring had in bringing about significant changes and improvements to environmental protection in the US during the 1960’s. In response to this movement and to help mediate the laws that were being drawn up by separate states and cities, Republican President Richard Nixon founded the US EPA in 1970. The US EPA continues to set national guidelines as well as monitors and enforces those laws, such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. While Nixon won’t go down as one of America’s most popular presidents, his actions and those of other Republicans in power demonstrate that the GOP is historically not an anti-science group. President Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in setting up the US Food and Drug Administration, set up five National Parks and numerous National monuments, and went on a few scientific explorations of his own. Senator Barry Goldwater, also a republican, was an advocate for environmental protection efforts in the 1960’s, saying: While I am a great believer in the free competitive enterprise system and all that it entails, I am an even stronger believer in the right of our people to live in a clean and pollution-free environment. To this end, it is my belief that when pollution is found, it should be halted at the source, even if this requires stringent government action against important segments of our national economy.” Science is not inherently bipartisan, but scientists, and the issues that they tackle, do have political biases. A danger of a politically-charged event like the March for Science is that it may undermine the public’s perception of a scientist as being a politically unbiased person. The way in which we choose to stand up for our work as scientists has to go beyond the March for Science. It requires us to develop a clear message of how science can provide support or guidance on the policies our representatives adopt on. Regardless of who is in charge, scientists should always advocate the utility of science and to help enable government policies founded on science, not on political biases. After the march, scientists can work towards this objective by sharing their thoughts and concerns directly with legislators. We should support our representatives who are working on legislation to support clean air and water policies and bills that provide protection for government scientists. The April 22nd march is a way for scientists to take a stand against the injustices inflicted by the current administration. It’s important that scientists make their voices heard, but we as scientists also need to make sure that the message we are sharing is a clear one: Scientists and researchers are here to help make our world a better place, and we stand beside everyone, in solidarity, for a better tomorrow.

A new study shows how a bee’s exposure to pesticides can cause significant changes in its scent memory abilities. The chemical formulations that kill mites may be non-lethal but can still harm bee populations.

Findings reported in the January issue of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry found that bees exposed to a pesticide used to exterminate mites within honey bee hives have changes in their behavior. They also found that these changes could be related to the expression levels of genes that encode key proteins in the brains of bees. In particular, three genes essential for scent memory were changed after pesticide exposure. Researchers from the University of Toulouse and the Jean-François Champollion University in France conducted exposure experiments with Western honey bees. Bees were exposed to the mite-killing pesticide Apilife Var for 11 months, and gene expression levels were compared to levels in the brains of unexposed bees. The study also evaluated if pesticides changed the way bees responded to scents. Apilife Var is a pesticide that kills mites and is made of natural extracts such as thyme, menthol and eucalyptus. These pesticides are effective against bee mites and are also known to affect cognition in mammals. Studies show that thyme extracts help rats complete maze tests and menthol can improve memory in rats. The protein expression levels of bees from this experiment showed seasonal differences during winter months. Three proteins decreased in bees who were exposed to pesticides 2-3 months after the start of the treatment. The proteins include transient receptor potential–like (TRPL), resistance to dieldrin (RDL), and Apis mellifera octopamine receptor 1 (AmOA1). In bees and other insects, TRPL helps bees avoid harmful chemicals. In theory, changes in the amount of this protein could cause confusion on whether a chemical is toxic or not. This could potentially cause bees to engage in unnatural behaviors, such as seeking out environments with harmful chemicals. The other two proteins studied are RDL, a neurotransmitter receptor and a neurotransmitter receptor that is crucial for learning. The study also found that chronic treatment with pesticides changed the way bees responded to scents. Exposed bees were more likely to respond to a scent that they were conditioned to associate with food. These bees were also more likely to remember that the scent was related to food after conditioning treatments. These findings provide additional understanding of how the pesticides can impact honey bees. Other studies have shown how these chemicals can hamper behaviors like learning, foraging, and scent memory. The genes studied in this paper are found in the octopamine pathway and includes proteins related to scent memory, sugar responses, and labor division. High octompamine levels are also correlated with bee anxiety. Long-term use of pesticides are associated with widespread honeybee population losses in Europe. A retrospective study showed that close to 10% of the honeybee population decline could be attributed to pesticide use. In 2002, new oilseed rape plants were introduced in the UK with seeds already coated in pesticides. Since the pesticide is water soluble, the plant takes up the chemical from its roots and the pesticide then circulates throughout the plants stems, leaves, and flowers. The coated seeds were a “key innovation” that avoids the need to regularly spray chemicals. However, the widespread use of the pesticide-covered rapeseed, and the exposure of bees to the pesticide while foraging, is now thought to be associated with bee population declines. Three pesticides from a class known as neonicotinoids were banned by the EU in 2013 because of their harmful impacts on bees. Farmers were concerned about the ban but there were no reported decreases in rapeseed oil yields in the UK after the ban. The use of these types of pesticides are still under review by the European Commission.

After this last week of news, I wanted to use this post to talk about the role of government policies on the environment and the impact of science communication and journalism on policy. To bring some hopefulness and optimism into the discussion, I thought it would be a great time for another one of our Heroes of Science posts. This week’s hero is Rachel Carson, a marine biologist turned conservationist and science writer. Carson fought an uphill battle to protect wildlife and human health in the 1950’s through her book Silent Spring and her tireless efforts to connect with scientists and politicians.

This post is not meant to be a complete summary of the life of Rachel Carson but rather a presentation of the context of her life and work and why we feel she is a hero of the scientific community. If you want to learn more about Carson, check out our sources of information here and here. Carson was born in 1907 and grew up in rural Pennsylvania, where she enjoyed spending her free time exploring the lands around her family farm. In addition to studying the natural world, Carson was an avid reader and began her collegiate career by studying English before switching to biology. After graduating with a Masters degree in zoology and needing to take care of her family, Carson started working part-time at the US Bureau of Fisheries instead of going for a PhD. In the Bureau she was in charge of writing scripts for radio broadcasts that focused on aquatic life as a means for the Bureau to inspire more public interest in their activities. In addition to her work writing for “Romance under the waters”, Carson was an active freelance writer and was regularly submitting articles about fishery science to local newspapers and magazines. In 1936, Carson was promoted to junior aquatic biology position and became only the second woman to earn a full-time job in the Bureau of Fisheries. While busy analyzing and reporting data on fish populations, she was also regularly writing brochures for the public as well as writing regular articles for the Baltimore Sun. Carson soon became an even more active writer, expanding into Nature magazine and publishing her first book Under the Sea Wind in 1941. Critics welcomed her engaging prose and her in-depth knowledge on the topic, but sales were not as high as publishers had hoped. Her second book The Sea Around Us was serialized in Science Digest and was a much larger commercial success, giving her the support to pursue a writing career full-time. She then transitioned to working in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy and shifted her topics from oceanography to conservation. She soon became interested in a newly marketed chemical called dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (or DDT for short). The chemical was only recently being tested for its safety in the environment after extensive use during World War II. The Nature Conservancy was trying block the widespread usage of pesticides such as DDT, which were being used to kill fire ants and other insects. In 1959 the USDA responded to this increased concern about the topic with a public service film “Fire Ants on Trial” to highlight the benefits of pesticide use and brush off the negative health claims. Carson described the film as “blatant propaganda” as she continued to write articles about the connections to pesticide use and plummeting bird populations. Her work highlighting the issues with pesticide over-use and toxicity later became the foundation for what would become her most famous book: Silent Spring. While summoned to an FDA hearing after high levels of pesticides were found in cranberries grown in the US, Carson saw first-hand the powerful influence that the pesticide manufacturers had in the hearings. Some discussions even went so far as to contradicting the expert testimony provided by the invited scientists. Amidst government panel hearings, article writing, and battling cancer, Carson finally published Silent Spring in 1962. The book compiled research and information from the mid-1940’s when DDT was just coming into prominent use. The book contains numerous examples of the extensive environmental damages which were attributed to broad DDT use and also highlighted studies from cancer biologists whose data had led to the classification of many of the pesticides as carcinogens. When the book was published, it wasn’t received with the level of accolades and support it has today. The book gained many critics and the publishers and Carson were afraid of being sued for libel by the chemical companies. But Carson had support in the science of her arguments, with each chapter reviewed by scientists and in whose support she relied on after publishing Silent Spring. Carson also sent an early copy to Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, an environmental advocate who rejected a previous case that would have allowed DDT to be sprayed on Long Island. While DuPont and other members of the chemical industry did threaten to sue upon publication and responded to the book with a public campaign on the safety of pesticide use, Carson and her team were ready. Lawyers had arguments bolstered by the confidence in the scientific truths which were being presented. Some scientists did lash out at Carson—one biochemist stated that she was unqualified to make the sort of claims she did since her background was only in aquatic biology. She was accused of trying to return civilization to the Dark Ages crawling with vermin and bugs, and was even accused of being a communist. But the scare tactics and name-calling were ineffective. Thanks to the support from scientists, the book achieved its goal of increasing public awareness on the dangers of pesticide overuse. The topic appeared as a CBS special report, including interviews from scientists on TV, which soon led to a congressional review of pesticide use. Carson spoke again to a congressional review board and this time her appearance was followed by a report from the science advisory committee that backed Carson’s story. She was able to see the impact of her work and receive numerous honors and awards for her efforts before passing away due to her failing health in 1964. Carson’s work left an enduring legacy: it was a rallying point for environmental conservationists. It helped led to the creation of the EPA and the subsequent banning of DDT. To this day Silent Spring is considered a story of the victory of science, environmental health protection, and accurate risk communication, an inspiring story that is still pertinent today. Carson is one of our heroes of science because of her courage in showing future generations how to stand up for the truth to protect the world we live in. She set an example by working with scientists as an engaged journalist and writer. She followed her own lead and thoroughly analyzed the scientific literature she wanted to highlight. Carson shows us all that through collaboration and determination, work that is done in the light of truth and for the greater good can always persevere. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed