|

In previous posts I laid out five (plus/minus one or two) easy* steps for developing a scientific presentation. For today's post I'll be going into more detail about the preliminary work that you should do before you set off on making a perfect** presentation. As an added bonus, you'll get a sneak-preview of my presentation at the upcoming Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) North American annual meeting located in the ever chic and always stylish capital of Utah, Salt Lake City. So not only do I get a blog post from my efforts, I'll have already put some time and effort into my talk before I get to the meeting. That's what we call in science a win-win situation, and in my case even better than free pizza at a seminar you were already actually planning on going to.

*Easy: Remember that nothing good in life comes that easy, as evidenced by the fact that I spend 3 hours making 4 slides for this talk. **Perfect: In the end I'll probably end up getting nervous and making a sarcastic comment about how my bipolar membranes look like lollipops, but that's OK, because the story is what’s important and the story is what they’ll remember. Step 0. Make a story board For my SETAC presentation, I get 12 minutes for the talk and 3 minutes for questions and answers. Following the presentation rule of thirds means the first 1/3 is background/broad appeal, the second 1/3 is in-depth details and concepts for people in my field, and the last 1/3 is my novel contribution to the field. Because of this, I printed out blank Powerpoint slides in groups of four. I'll focus on having 4 minutes of background information/introduction, 4 minutes of detail-oriented methods and ideas relevant for my results, and 4 minutes of my actual results. It may sound like a small amount of data, but having given a good overview of the big picture of my project, as well as a bit more in-depth review of relevant methods will make the data I show more clear and understandable, and therefore more memorable.

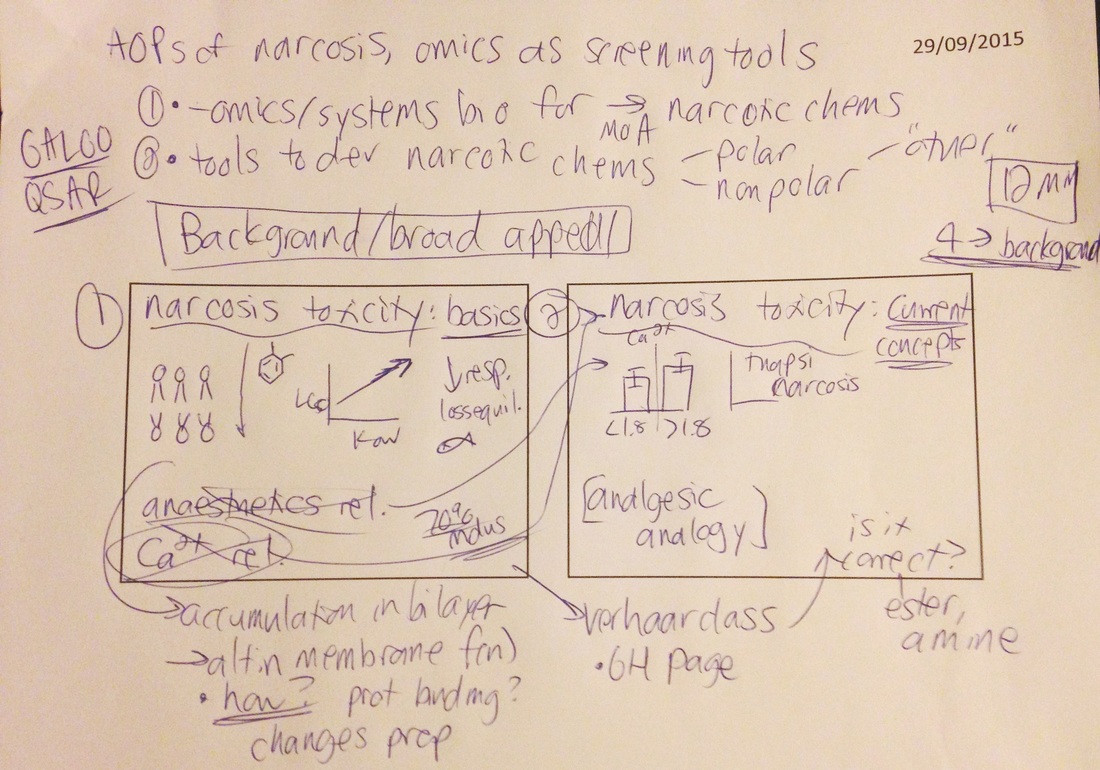

With my storyboard printed and ready to go, I started off by going back to the original conference abstract to make sure I set off to present what I said I was going to present. I started with putting two things in my mind: the objective of the work to present in my talk and my audience. Writing down your objective again before starting on slides helps focus your mind on the bigger picture of what you want to present. In my case, the objective of the data for my talk is focused on the molecular mechanisms of narcosis toxicity and developing new screening tools for different classes of narcotic chemicals (as part of my post-doc project with Unilever). My audience in this case is one I know quite well: SETAC regulars who will be coming to the session on '-Omics technologies and their real-world applications.' There will be quite a few people in this audience that I'll know personally, and others whose work I'll be mentioning in my slides. No pressure!

With my audience and objective laid out, I set to work on the slides. Following the rule of thirds, I started off with background information/broad appeal, to get everyone on the same page. While most of this audience will know about concepts like gene expression, risk assessment, and adverse outcome pathways, I want to make sure that someone popping over from an environmental chemistry session will also be able to follow along. At the same time my subject area is not one of the hotter topics at SETAC, so a bit of background in terms of biology and relevance is necessary here.

I decided to start off my talk with a description of narcosis toxicity. As I said, this isn't a hugely hot topic in my field, so I planned on making the first two slides as an opportunity to teach anyone in the audience who hasn't heard it much before. I split this into two parts, one focusing on the basics/textbook toxicology concepts of narcosis, and the second going into more details on recent papers and new understandings. Here I also sketched out what to put on each slide, including my lollipop-esque membranes, and what figures from the literature I wanted to include.

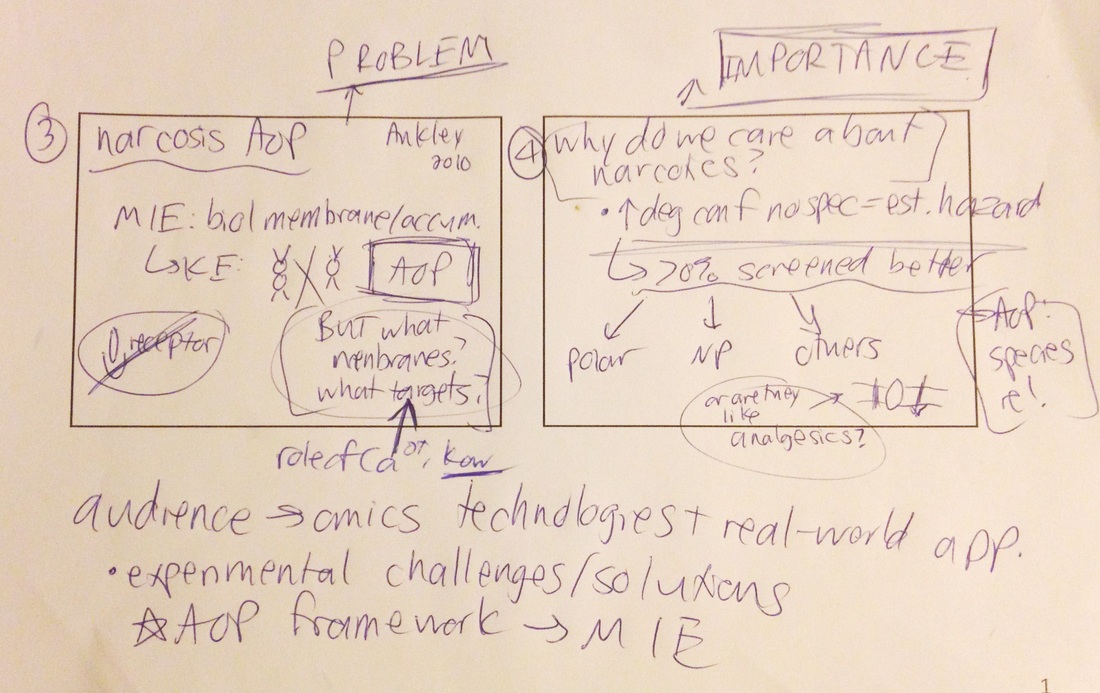

So now that I've put everyone on the same page about what narcosis is, I'll then present the specific problem I'm looking into, in this case the lack of understanding of the molecular mechanism of toxicity. This will be in the context of work done by senior scientists who will most likely be in the audience, so I've made a note to cite their work. This brings in concepts that I discussed in more detail in Step 1 of the perfect** presentation, where you get people's attention by describing a problem in your field, why that problem is important, and then in the next slides how you solve it. For this talk I present the problem and then talk about how knowing mechanisms of toxicity are relevant for accurate risk assessments for chemicals, especially narcotics. Hook, line, and sinker!

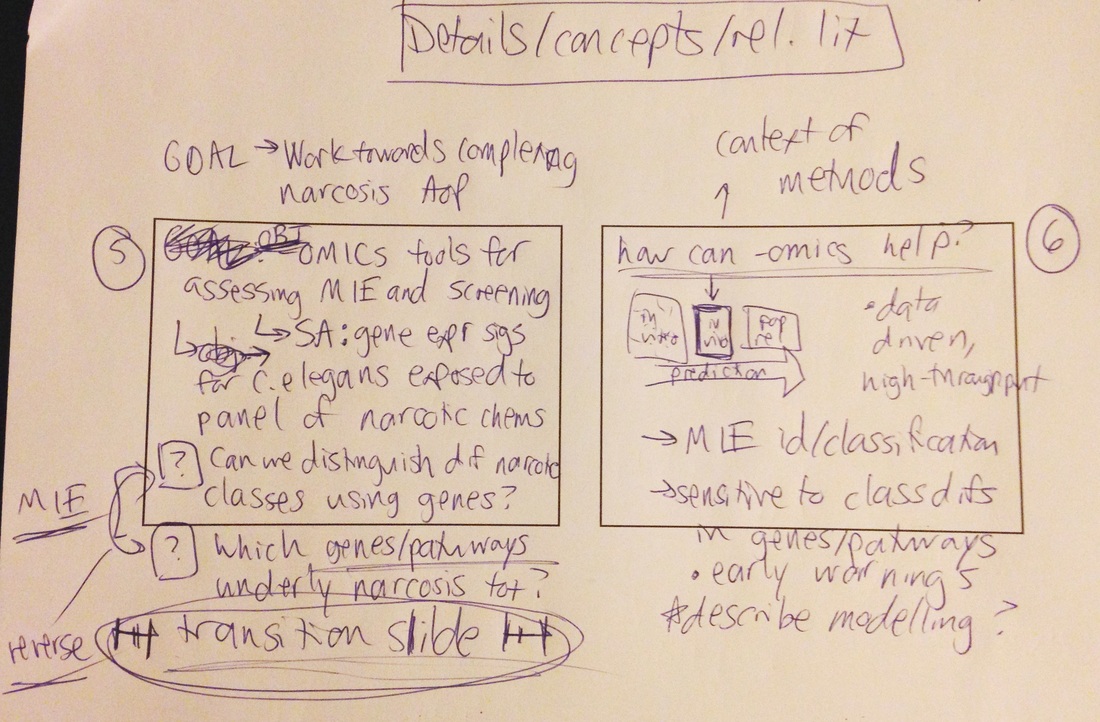

At this point I've now laid out the objective of my project, the specific questions I'm asking, and how they will address the issues I presented in the introduction. This slide (#5) also comes at a time where I am transitioning between background information and getting into the nitty gritty of my project. You can skip trying to decipher my bad handwriting and read more about Step 2 and how you present setting out to solve the problem you just talked about.

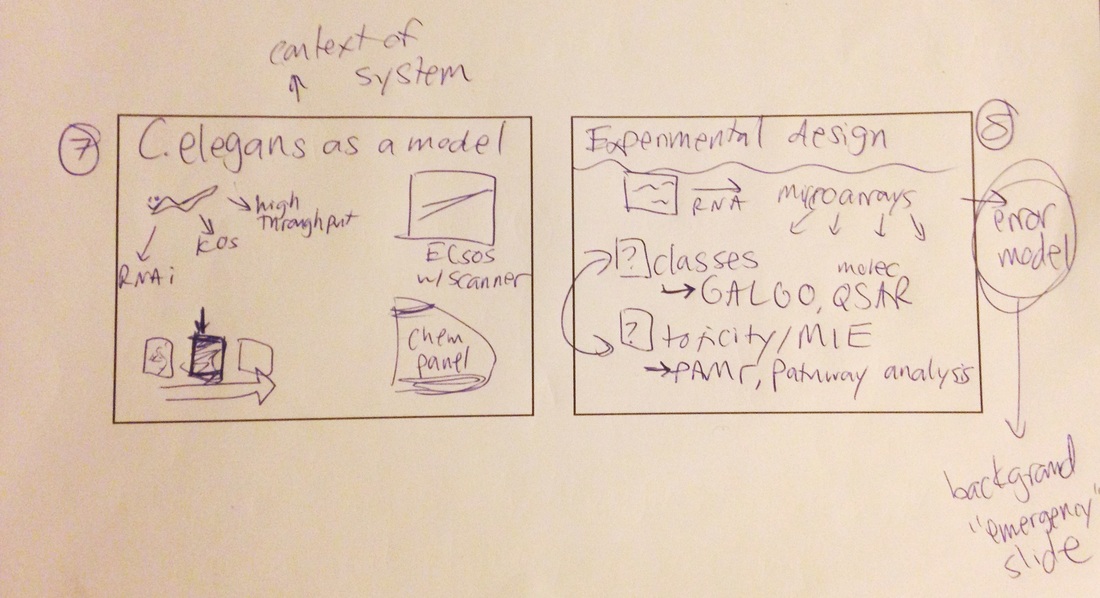

After the transition slide and describing my project's objective and questions, I then go into a bit more background information to provide context for the data which I'll show next. This includes one slide (#6, see panel above) on how high-throughput molecular techniques can help address these questions, and one slide (#7) on my model system and why we chose it, including background information of toxicity of narcotics in my model system. I then give a schematic of my experimental design and will talk here about the analytical methods I'll be presenting. I also made a note to myself to make an 'emergency' slide with details of one of the methods of my project. As its only a small part of what I'm doing but something that a few people might question, I'll make a slide to have at the end in case I get a question after the main part of the talk.

So with those eight slides I'm now 2/3 done with my talk. The last four slides will be data and conclusions, and to prevent any earth-shattering findings from escaping into The Internet too soon (and to motivate any SETAC meeting attendees to actually come to my talk, on the last day of the conference in the late afternoon!), I'll save those sketches for when I make the real thing. Step 1. Set the stage and Step 2. The Hook To give you a sense for how the introduction slides actually ended up looking, apart from my terrible scribbling, here are how they turned out so far. I added animations in the actual presentation so the content doesn't all come up at once, which also allows what I say and the components of each slide to come together in a more logical progression. As an aside, I have no idea the appropriate color for biological membranes, so I am currently thinking of new ways to see if I can make a bipolar membrane not look like blueberry lollipops. To be determined for the next blog post.

As you can see, there's a lot you can convey with lollipops and arrows, and remember that at the same time that your slides will be on screen you'll also be speaking (as scary of a concept as that seems). Think about how your words and your slides can work together, and keep to a minimum any redundant or unnecessary text as well as figures or diagrams that may be too detailed or too small to see or understand clearly. Before jet-setting off into your experimental design, take a slide to transition from introduction to experimentation while at the same time giving your audience a clear vision of what you are doing and what scientific questions you are answering (e.g. the hook).

While I've touched briefly on some of the last three steps while working on my storyboard (the story, take a bow, and break a leg), we'll save a more in-depth analysis of these for when we get closer to the actual meeting. It will also give me a chance to finish making my data slides, and to practice my talk before giving the real thing to a live, scientific audience, including but not limited to collaborators, experts in the field, and potential future employers. Again, no pressure. Until next time, happy storyboarding! Rubber versus steel: Finding the balance between flexibility and strength in work and in life9/23/2015

In the summer of 2011, I went on a scientific pilgrimage to Japan as part of a quest for knowledge and self-discovery…or at least that’s the way I’ll present it in my autobiography and made-for-TV movie life story. In reality, at the end of my 2nd year of my PhD I was awarded an incredible fellowship, the East Asia and Pacific Summer Institutes, from the National Science Foundation. This fellowship was coordinated in Japan by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Summer Program, and the program is also available for those of you from Canada, Germany, UK, Sweden, and France. During my two month fellowship, I worked at the Center for Integrative Bioscience in Okazaki with of one of the molecular toxicology greats, Dr. Taisen Iguchi, and under the direct tutelage of Dr. Yukiko Ogino. Her papers on sonic hedgehog gene regulation in mosquitofish were some of my most-read papers in grad school and she was something of a science hero for my PhD project. Trying to finish in situ hybridizations and fish exposures in such a short window of time was exhausting, but I loved the work and the lab and the chance to spend a summer in Japan.

In between work, sightseeing, sweating, and eating copious amounts of katsudon and unagi, I spent some time getting back into martial arts, not really as a pre-planned activity but rather something that came about as a whim. I had mentioned to one of my Okazaki lab mates that I was curious if there were any karate schools in the area, and with that one brief mention she set to work and I was whisked off the next week to my first class. I didn’t have time to back out or say no thank you, so instead I went with it. It was only two days a week for an hour at a time, so I thought it wouldn’t be that much of a hindrance on the rest of my jam-packed in situ hybridization, sightseeing, and sweating schedule for that summer. As with everyone I met in Japan, the instructors were incredibly friendly and helpful. While English didn’t come easily for some, all of the black belts tried their hardest to teach me the moves and to explain the stances and forms as best they could. I never really felt that I caught on as well as I could, likely only partially due to the language barrier and more with the fact that karate was very subtly different from tae kwon do. A bit more of a flourish to a block, a foot that was slightly at an off angle for a stance, and at the end of a long day at work it was easy for my arms to get twisted in knots instead of making smooth movements. Nonetheless, I really enjoyed my time as the class’s gaijin (foreigner) and white-belt-in-training. As the summer progressed and I became less awkward in my movements (and better at following the commands in Japanese), I was invited to attend a class at the main dojo in the neighboring city of Aichi. I soon learned that my little Okazaki karate school was affiliated with a HUGE school, with branches and classes all over the Aichi prefecture, all coordinated by an absolutely enormous dojo at the prefecture capital where I was headed to meet with the Grandmaster himself. The instructors at my school did quite a bit to prepare me to meet with the Grandmaster. Between the small language barrier and their descriptions of how I needed to be polite and respectful at all times, I had the impression that I was meeting the Lord and Master of Karate himself. I was a bit nervous to meet him, especially as the only American in a room of Japanese karate students, and I wanted to do my best to leave a good impression. Needless to say, the train ride to Aichi for the first lesson was a bit nerve-wracking. I soon found that Grandmaster Jun Tamegai was actually one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met. He was so excited to meet me and had one of those electrifying and warm smiles that made you feel completely welcome and relaxed. Then when class started, he suddenly became very intense as he instructed his students, myself included, with one of those auras that made you want to do everything he said and do it at 110%. Even after the very warm welcome, I could see why I was prepared by the black belts at my school for this meeting, and why all the other instructors both adored and respected him. He seemed like the kind of person who would invite you into his home for tea and katsudon while being ready at a moment’s notice to take someone out at the kneecaps if they snuck up behind him. I went to the main school in Aichi for a few lessons at the main dojo, each time being given the honor of a one-on-one lesson with the Grandmaster. His English was good, although hesitant, but that seemed more from nerves at speaking with a native speaker as opposed to not being good at English, or perhaps he just wasn’t that talkative. I cherished these one-on-one lessons and was even more surprised when he invited me to a barbeque along with the other black belt instructors from my school. It was my last weekend in Okazaki and I spent the day at a lake with these wonderful people, enjoying some lakeside activities, and eating delicious teppanyaki. At one point in the day, I went on a jet ski ride with the Grandmaster, speeding around the lake at more than 90 km/h (he seemed to get a kick out of my incessant screaming as we drove around the lake at seemingly impossible speeds). At the end of the day he gave me my last lesson and I went back home to Okazaki (after even more delicious izakaya food). I was truly and deeply thankful for everyone in the school’s patience, hospitality, and guidance that summer. I was happy for that whim of mine that became a reality. While I’ll probably never really get the hang of karate due to too many years of training for tae kwon do motions and stances, I took home several lessons from my summer karate camp, lessons that reflect back not just on martial arts but on my work as a scientist and on living a life of balance. In one of the private lessons, the Grandmaster introduced me to the concept of rubber and steel in karate. Rubber meant being flexible, relaxed, fast, and able to move freely and easily. Steel meant being strong, unwavering, persevering, and able to withstand whatever you’re put through. Grandmaster told me that both rubber and steel were important, that you couldn’t just be good at one, you needed both if you wanted to excel at martial arts. He told me this in the context of his own views of me and how I looked when going through the motions in class. He was the first person to tell me that I had so much steel, so much power and fury, but that I needed to be more rubber if I was going to improve. I continued to think about that lesson in the rest of the summer, at the same time busy finishing up my project in the lab and trying to travel to as many places as I could get to before my flight home. I thought about Grandmaster himself, the man with a welcoming smile and a ferocious intensity, both coming from the same person. I thought about his vision of me, of all my steel. Was I just too much steel in martial arts, or was I too much steel in other parts of my life as well? The concept of rubber and steel isn’t just about how you punch and kick, it’s about how you react to the world around you through good times and bad. Work as a scientific researcher, and as a graduate student especially, is a place where you can certainly feel like you need to punch and kick your way through, the fight for survival in academia and the cut-throat world of science. It’s here that the concept of finding the balance between rubber and steel is something that the Grandmaster can teach all of us, in order to help us find the balance between our own natural tendencies and to help us recognize when we need to be more rubber or more steel in order to improve and succeed. As Grandmaster noticed, I was more steel, and in hindsight I probably was more steel long before starting the karate lessons. I have always been very hard-working, determined, strong of mind, and unwilling to give in. I always did well in school, from my first day in kindergarten all the way through my undergrad studies. I worked hard to get good grades and hear praise from my teachers, and after getting my bachelor’s I set out to do a PhD program and to change the world through my research. On the flip side, I would become frustrated when I ran into walls and couldn’t progress with what I was doing, feeling like I had nowhere to go. I was self-confident when doing well but would lose that confidence if I slipped even a small amount. I always worked relentlessly, coming in on weekends and after hours to try to get as much data as possible. I was set to succeed and would let nothing get in my way. The problem with being all steel is that it makes you rigid and frustrated when you can’t do something right. It can make you feel anxious and tight for no reason other than your need to succeed. Steel might not wear out easily, but being 100% steel all of the time will undoubtedly wear you out. But if steel is where all the strength and perseverance is, then what’s so great and useful about rubber? Rubber is about relaxing in the face of stressful moments, of going with the flow of life and the problems that come at you. Rubber is about coming to a wall and bending around it instead of trying to break it down. Rubber is about not doubting yourself even when you slip and stumble because you know you can adapt and mend. Being rubber means you stay loose and free instead of tight and anxious. But as with steel, being too much rubber does not make for a balanced life. Too much rubber can mean that you’re so relaxed that you don’t do anything and don't feel an urgency to work hard at something. Too much rubber can lead to too much flexibility and wavering instead of following a plan of action. Rubber is fast and flexible and free, but if you’re 100% rubber then you won’t stand up for what you believe in or persevere when things get difficult. When you examine your own tendencies, you’ll likely find that you tend to spend more time as one over the other. While steel people are hard-working and tough, if driven too hard they can end up defensive when challenged, short-sighted about finishing a task because it needs to get done, working long hours without having a concrete reason, and when stressed may not be as likely to ask for help or reach out to others. On the other side, rubber people are cool and calm but may find themselves being lazy or distracted during working hours, may lack of motivation in completing a task, can have a tendency to procrastinating, and can end up juggling around side projects or ideas instead of staying focused on a single project or concept. In addition to knowing your own tendencies towards rubber versus steel, another point of the Grandmaster’s lesson is to know when to act like steel and when to act like rubber. There are times when you need to be steel, when you need to stand up for your project and your work and defend what you know to be true and right. There are times when you need to just power through something, whether it be data analysis or a day’s worth of pipetting, in order to get things done. On the flip side, there are times when you need to be flexible to changes in direction in your project, times when you need to stop doing the same assay over and over and look at what the data is telling you about where you should go instead. There are times when you will be challenged and the only way to come out ahead is to walk away or change directions instead of fighting back. The key is to recognize the need to find the balance and to focus on embracing the good parts of rubber and the good parts of steel. Finding a balance is about knowing yourself as much as it is working towards that balance, because knowing your tendencies will help you figure out where you need to go. Steel people need to know when to relax and be flexible to challenges, rubber people need to know when to stand firm and stay focused. By recognizing if you’re more rubber or steel as well as seeing when to embrace either your rubber or steel side, you can get closer to achieving that balance between cool, calm, and collected, yet ready to strike at a moment’s notice. While I’m still striving for finding my own balance of steel and rubber, I often think back on that summer and the tutelage of Grandmaster Tamegai. I finished my time in Japan with a 5-day excursion exploring around Hiroshima and Kyoto on my own. I found myself really relaxed, reflecting on a great and productive summer, but at the same time a deeper sort of relaxation than I’d had before. Was this what being rubber was all about? I still strive for that relaxation in my life, which is sometimes more difficult than it was during that 5-day train trip exploring oceanside shrines and eating katsudon. For me, becoming more rubber is still a work in progress, but recognizing when I become too hard or shortsighted or frustrated helps me know when I need a break or when I need to step back and take a breath. At the same time I’ve learned to embrace my steel side, knowing that it can bring me focus and determination and can help me push through difficult times that need to be pushed through. I hope someday to have that same balanced demeanor and attitude that Grandmaster had, with the warm smile that welcomes you as his friend accompanied those powerful eyes that stay focused and locked on target. Although I’ll likely refrain from driving around students on a jet ski while going 90 km/h. But maybe that’s just another lesson I didn’t learn yet. A final note: If you are still a graduate student from the US, UK, Germany, France, Sweden, or Canada and are interested in having a rewarding research stay in Japan, check out the JSPS summer program and apply to go on your own spiritual summer science quest. やった!!

Every week when I think about what to write for Science with Style, inspiration seems to come at the very last moment, and so far most of my blog posts have been inspired by my own recent experiences (and frustrations) in academia. Today’s topic is no exception, as I’ve been thinking about both my own blog procrastination and the selection of manuscripts I’ve left untouched. While I enjoy writing both in my personal and professional life, I still find myself having writer’s block on more than one occasion. Manuscripts which came back rejected that I never got around to working on, grant proposals and reports that I just can’t figure out how to start, and an ever-growing list in the back of my mind of emails I need to send or reply to. What is it about putting our thoughts and ideas into the written word that’s just so damn hard sometimes, even for those of us that enjoy writing?

I’ve asked several friends and colleagues recently what they think about writing and why they do or don’t like it. Some of the responses I’ve collected include It’s DULL, I’m not good at it, It takes up so much time, I feel like I’m just repeating what’s already been said, and the list goes on and on. While it seems there are a lot of reasons to dislike writing, the complaints about writing which lead to our procrastination can also arise in other parts of being a scientist: putting off the ever-growing pile of papers to read or the endless hours of pipetting required to load PCR plates. There are a lot of things that feel tedious, that we think we’re just not good at, or that we feel are a waste of our time, so what makes writing stand out in the crowd of things that scientists just don’t like to do? Writer’s block isn’t just about a lack of motivation to write, it usually arises from something that goes deeper than a simple inability to put words onto paper. Maybe the data you need to write that manuscript about wasn’t quite as ground breaking as you thought it would be when you set out on the experiment. Maybe you realized as you’re writing up a project report that you need to dig through the raw data again and run another statistical test before you send it to the grant agency. Maybe you’re having trouble explaining your results, or aren’t sure about presenting findings that go against what someone else published already. These moments will come frequently in science, as there will be an answer to a question that goes against what we (or other scientists) thought would happen, or moments when we realize that what we analyzed needs a bit more work than we wanted to put in. Wherever the block in our writing comes from, the fact is that as scientists-in-training and as future leaders of the scientific community, we need to write. We need to write in order to share our work with our peers, we need to write proposals in order to get grants to fund our labs, we need to write emails for collaborators and students and technicians in order to get things done. This is again in contrast to the expected image of a stereotypical scientist, and likely wasn’t what many of us imagined spending our days doing when we became fascinated with the natural world at a young age. That being said, it’s crucial for scientists to take a different approach to writing in order to make our work and our research more impactful using this communication tool. As scientists, we need to work frequently on transforming our thoughts and ideas into the written word. To do this effectively, we have to learn 1) how to get motivated to write and 2) how to write. Writing in science and about science is so important that it will likely be the theme of multiple blog posts from here on out, but for now let’s start by getting inspired to put pen onto paper (or to be more accurate in this day and age, opening one of those much-dreaded empty Word documents): - Get inspired by great writing. Great writers are also avid readers. We absorb a lot of the ways we speak, think, and write from the world around us, so if you want to become a good writer and become more inspired to write, then reading more will help. Outside of your work, read what you enjoy and read to broaden your perspective, whether its history, psychology, classic literature, or scifi novels. Take time in your week to let yourself be entranced by the written word, since reading the works of great authors can help you become inspired to make some great works of your own. While fictions books are great and these stories can help us unwind after long days in the lab, you’ll generally want to keep the way you talk about your research separate from the realm of fiction novels. Finding a favorite non-fiction author, authors who focus on facts, citations, and logical progressions through events, can help your writing become more inspiring while still being fact and logic driven. My personal favorites include David Grann and Neil Oliver, but there are certainly many other great non-fiction authors out there that focus on topics other than South American explorers and Celts, depending on your own nerdy interests. In addition to always having a book in hand (or in your Kindle queue), find scientific authors you enjoy reading and keep up with their work, even if it’s not 100% relevant to your specific research project. Many of the papers you will have to read will be rather dull, because a lot of those papers are written in an uninspired way (yet another reason for you to get inspired and make better ones!). That being said, there are also some fantastic scientists who produce clear, understandable, and well-crafted papers that can encaptivate you as much as a good novel. Stay on the look-out for these research groups; read what they produce, see how they set up their manuscripts, and try to incorporate their outline and transitions into your own scientific writing style. - Envision writing as an opportunity. It’s easy to think about writing as a dull task that we have to do in order to get grants, enough manuscripts to graduate/get a tenure track position, etc. That’s also an easy way to make writing a more difficult task than it actually is. This is especially true for PhD students, as many of us (myself included, flashing back to 2 years ago me) think that writing a thesis is a pointless task because in the end ‘no one will read it.’ That’s, unfortunately, probably true, but there is a purpose to the task, and it’s to help you become a better scientific writer and to put into written words all of the assays and analyses you’ve done over the past 3-5 (or 8+ for some) years. As you likely already know how crucially important writing is for a successful career in science, then it’s evident that writing an 80-100 (or 200+) page dissertation/thesis is just a small part of what you’ll be doing the rest of your career. And as they say, practice makes perfect! As scientists, we should envision writing as a chance to teach peers in your field something new, to tell a story about a piece of the world you’ve figured out with your research, and to show the scientific community that your time spent in the lab and chugging through spreadsheets was done for a purpose. What helps inspire me in my writing is to look back at the big picture of the problem(s) in my field, the specific questions I’m asking in my work, and think about how things fit or don’t fit together. With this mindset and frame work I find that I enjoy writing more, when I don’t just look at it as Oh I need to write such-and-such paper but instead as I have a chance to take a step back, look at my field, and ask and answer a question that’s relevant for it. As scientists our job is to interpret the world and to explain new pieces of information that we get from it, and writing is an excellent chance to help frame our minds around these new ideas and concepts. - Choose your audience when possible. Don’t just think about what story you want to write but also what types of people will read your story. We spend a lot of time selecting journals based on impact factor, reviewer turnaround time, accessibility, etc. What’s equally important however, and oftentimes forgotten by both students and professors, is that part of your choice should also be focused on who is going to read your paper. Do you want to reach the wider scientific community and talk about the broader scope of your research or stay within a smaller group of scientists? Does your work have more of an impact on a basic research level or is it more focused on application? Do you want a journal with a focus on open access publication or do you just care about scientists whose affiliations cover any publication access costs? These are the types of questions that should go into the decision making process of where to send a paper. Your PI and co-authors will likely have some thoughts on this topic, but remember that this is your story and you should have a voice in who you tell it to. Selecting your journal and audience before starting out will also help you organize your paper. Just as knowing who your audience is in a talk will help you frame your slides, knowing who will read your paper will help you determine what you put in the introduction/discussion and what you make as a take-home message. This exercise of thinking about your audience is also a great way to become better at writing non-scientific papers, such as for community outreach projects, blogs, or making a layman’s interpretation of your project. Thinking about framing your writing for your audience, even when you know the audience quite well, can help you become a better writer when all of a sudden you have a new audience to talk to. In the end, avoid trudging through all the details and instead focus on enhancing the clarity of your work and its impact, which will always make your writing better, no matter who it’s for. - Ask for help and get a second opinion/perspective. As with many aspects of grad school/academic life/science in general, sometimes we really need a helping hand. Talk to friends and fellow grad students about your writer’s block, tell them your ideas and thoughts and see what they say about potential gaps, issues, and ways to move forward. Talk through your frustrations, either about your specific project or with a paper itself, and get another’s opinion on how to tackle them. Oftentimes we are held captive by our own goals of perfection or our concern on the lack of agreement between our initial hypothesis and the results we obtained. Talking to another person about our road blocks can help us see what is holding us back and can tell us whether we are making too big a deal out of something small. A second pair of eyes is also good at spotting issues we might not catch and provides another perspective on our project and the problems we are looking at. While there’s certainly no definitive cure for writer’s block, finding ways to become inspired can ameliorate the symptoms and help you make progress towards sharing your story. Draw inspiration from others by picking out a new book or blog to read or finding well-written papers in your massive pile of literature for review. More importantly, become re-inspired by your own work and your own careers by answering these questions: 1) What’s inspiring for my career in science? 2) What’s motivating for my day-to-day work life? 3) What’s boring and makes me feel like quitting science? Writing may be the quick answer to the third question for a lot of us, but if you focus on the answers to the first two then you’ll likely see a place for writing in your career as a scientist. Many of us are inspired by unanswered questions, by problems left unsolved, or by a desire to make the world a better place. It may be a bit of a stretch, but writing can help you get there. Writing puts your ideas in a place for others to see and understand. It’s an opportunity take a step back from a problem and think about it in a new way from introduction to conclusion, by allowing you to take your months (or years of) hard work from the obscurity of raw data into clear words and figures that stand for themselves. I can’t make writing easier, but you can make it more relevant in your life by approaching it with a new mindset and by seeing how impactful the written word can be not just in our own h-index but in our identity as scientists. And now with this week’s blog post complete (again at the very last minute on this Wednesday night), it’s time for a much-needed break to build on thoughts of next week’s post, and to gain some of my own inspiration for finishing off that unfinished manuscript. So until next week, happy writing! How to make a fulfilling break: Using your time away from work to achieve a better work-life balance9/9/2015

People like to comment to me about how much I travel, asking where I’m jet-setting off to this weekend and if I ever stay at home. I’m not sure how to respond sometimes. Most of the time I’m proud of all the places I get to see and things I get to do, but occasionally the comments make me think that I travel a bit too much. This feeling is greatly enhanced by the irony that this week’s post is currently being written from a hotel room in Dublin on a RyanAir-enabled weekend away from home (with flights so cheap, why not?). While marking off cities and countries from my massive travel to do list is something of an obsession of mine, it’s also one of the major ways I unwind. Spending an afternoon wandering the side streets of a new city on the look-out for hidden cafes and photo-worthy architecture or scarfing down a ham and cheese sandwich on the summit of a hike are things I greatly enjoy. More importantly, these adventures, both big and small, help me unwind when I’ve been twisted and my tightened by stress, responsibilities, and the daily grind. Traveling allows me to rebuild my respective, refreshes me, and leaves me feeling ready to tackle my work's problem when I get back home.

So often as PhD students, post-docs, and senior academics, we feel like we just can’t take a break, as if something just has to be done right away. While there certainly are moments when deadlines and teaching commitments and emails pile on us endlessly, a lot of the ‘academic guilt’ comes during times when our workload is at more of a steady state. We very easily let ourselves fall into this mental trap, in which we think we should be doing something at every given moment: reading/writing a paper or getting lab results analyzed or trying to find a date for that continually-rescheduled meeting with your collaborators. Academic guilt is necessary, to some extent, for academic life to function, since a full-fledged academic is essentially their own boss and has no one to tell them during the day when they need to get back to the grind. At the same time, too much urgency can be a hindrance both to our productivity and to our work-life balance. For those of us working in academia, it's crucially important to balance our work with our personal lives, using well-timed breaks coupled with periods of sustained work. Scientists seem to be pretty good at the periods of sustained work part, but can be terrible at the well-timed breaks part. The key with taking breaks (and not feeling guilty about it) is to make each break a fulfilling one, one that leaves you energized for the rest of the day or week ahead. There are many effortless alternatives to working, as any Tumblr and Netflix binger knows all too well, but simply not working is not always a fulfilling break. In order to have a fulfilling break, one where you come back to your problem with a clear mind and a go-get-it attitude, you should use your free time to purposefuly unwind, unthink, un-everything. We all need moments to scroll through the vast wasteland of the Internet or to watch our favorite TV series with a glass (or three) of wine, but in order to come back to work the next day or after the weekend ready to tackle what you left unfinished, your free time can’t be spent with only these types of breaks. A break can be a large one or a small one, maybe a lunch outside on a sunny day or a Saturday out with friends instead of working on that experiment that just ‘has’ to get done. Whatever your schedule and needs are, a fulfilling break should enable you to do the following things: - Step back and see the bigger picture of what you’re doing and why you’re stressed about it. If there’s a hard deadline for a paper resubmission or grant application, it’s easy to see why getting things done for that time is stressful. But what about those moments when you feel rushed but don’t really have an explanation? A lot of the times that we feel stressed, we may not even know why and there may not be a concrete reason for it, or we might be making a mountain out of a molehill. Many people respond to stress by working, even when the stress originates from some other part of our life and issues outside the lab. Maybe your 10-year high school reunion is coming up, where you know all your classmates will ask what you’ve been up to for the past 10 years, which somehow triggers your memory into remembering that you didn’t work on that manuscript for a few weeks, and then, What have I DONE with my life, why didn't I just get a 'normal job' like all my other classmates, and also why do I have nothing to wear to the reunion? At times like this, its important to take a breath and consider whether getting more data points is really the solution for addressing what may be some bigger issue that has nothing to do with your research. At times like this, that weekend trip to the lake or an evening drink with friends instead of working nonstop can give you a better perspective on your life, your stresses, and the necessity of stepping back and taking a deep breath now and then. - Let your mind refocus when you run into problems. Problems in science tend to require a lot of focus to figure out. Why did all my cells die? Why am I getting this error message while running the data processing script that was working perfectly 2 days ago? Staying focused is good, but if you stare at something for too long you’ll lose your sight along the periphery. You can easily end up banging your head against a problem trying to throw everything you have at it, only later to recognize the solution while walking out of the building three hours later. Taking a step back from a problem, difficult or simple, is a good strategy because it gives you a chance to think about all the components of what you’re working on instead of the one thing that’s giving you trouble. Often times the solution was a simple one, maybe you forgot to add serum to your media or you saved your data file as a different format. Taking a break at the moments when you get the most frustrated can help allow your brain to get to those ‘a-ha!’ moments of remembrance and insight that can’t come when you’re staring a problem in the face and letting it get you flustered. - Let your brain disconnect from work, as much as it can. It’s difficult to unwire ourselves completely from our work, especially with those 11pm emails from your advisor asking what you’ve been up to in the lab for the past week. As hard as it may be, work on setting aside a part of your day and your week when you don’t check emails or work on the pile of data/papers you brought home. This gives your week more structure that you can fill with a fulfilling break, knowing that you won’t have to be bothered by some science emergency (which usually ends up not being a real emergency at all). Professors do tend to send emails at odd hours, perhaps due to their own odd life-balance, but likely it's because they just enjoy science that much and want to know what you're doing. It's both full-time work and hobby for some, but remember that you don’t have to reply to every one of their emails instantly. Most likely they’re releasing a barrage of emails to all their collaborators and students at once when they have a free moment, so don’t always feel like you’re being singled out. - Have Internet-free moments. In the wired workplace especially, this goes hand-in-hand with disconnecting from work. Whether it’s during the work week or on the weekends, take some time to unplug from your laptop/tablet/phone/whatever. Go to a museum with a friend, take a long walk somewhere new in your town, or go out to dinner and leave your phone on airplane mode. It’s hard to unplug when you have the world in your pocket 24/7, so when you have moments where you can enjoy the moment, be sure to do so. - Take time to focus on a different problem/idea/concept/activity. While binging on the internet and Netflix can help us disconnect, it’s not always the best way to focus away from work. We can get good at multi-tasking, watching TV at the same time as checking our phones or reading a paper. So make your brain take a break by thinking about something else. Read a Sherlock Holmes story and see if you can figure out the case before he does, dig our your oil pastels from your high school art class, learn how to say ‘the turtle drinks milk’ in a different language, or call your grandma and ask her if she has any extra knitting needles. Whatever suits your style, find something that you’ll enjoy doing that provides an external focal point for your brain, something that’s not as easy to let professor emails and thoughts of your next experiment slip in without you being ready to tackle them at your desk the next day. To find your ideal fulfilling break, all you have to do is look for something that fits your style, something that helps building you up when you’re feeling down and that unwinds your knots when you’re twisted around. My fulfilling breaks come both from travel and from tae kwon do. Both give me a reason to not check my phone for emails for blocks of time. Both give me things to focus on, like figuring out which trail or street to follow or remembering all the moves in my pattern. Both make me feel happy when I’m done (even though I may be physically exhausted from endless walking or kicking, depending on the activity), and that good feeling reflects back on the rest of my life and my work. Both take time away from when I could be reading papers or analyzing data, but when I do come back to work I feel like I have energy and take on those tasks with more fervor than if I just trudged through them constantly. I can also enjoy both at different time scales: tae kwon do is there twice a week to finish off a day in the lab, and travel is there on the weekends to clear my mind after a busy week (or two). There are also strategies you can use to relax during the work day to keep yourself from feeling like you’re banging your head against a problem or when you fall into a pit of unproductivity: - Take a walk. This is especially good for those of us that spend most of our day at a computer. You’ve likely already heard the lecture on taking a break from staring at your computer monitor so you don’t go cross-eyed, but stepping away from your monitor is also good for a quick 5-10 minute mental unwinding at work. If you feel yourself being unproductive or opening a few extra tabs of buzzfeed articles, take a walk somewhere in your lab building or make an excuse for a short walk around campus. A trip to the corner store or a lap around your building gives your eyes a chance to re-focus on the world and can let your brain think about the idea or problem you’re working on when you don’t have it staring you back in the face. - Have a fika. No, its not a new Science with Style candy bar (although that could be a good way to pay for the URL registration). ‘Fika’ is a Swedish word/concept which means ‘to have coffee’, but it’s more than just a way to get some extra caffeine. Fika is having a break with colleagues, friends, or family, and if you work in Sweden then you’ll even have a dedicated break time during your work day. It’s a time when you socialize but also to take a step away from your work for a few set moments of your day. You may not get a set time off from work (or have any fikabröds to go with your coffee) but you can start your own fika trend with office mates or lab mates and bring some of that Scandinavian culture to your own daily schedule (IKEA mugs and blåbär juice are a great fika starter kit, and tea is an appropriate substitute for those who prefer their caffeine from other sources). The hardest part about taking a break is that there are times when we feel like we just can’t. When we feel anxious about getting something done or that something MUST be figured out right away. The thing about a career in science is that it’s not an easy job to have. A lot of the answers are unknown and won’t always come to you easily, especially if you’re in an endless staring contest with them. Recognizing where your stresses come from as well as recognizing when you’re stuck can help you not only figure out what you can do to feel better but also to move forward with a problem and be more productive with your work. Any job, and science especially, comes with a lot of external pressures and stressors, but staying focused on the bigger picture of your world can help you face the stresses that you have to face and keep at bay the ones that you make for yourself. And now as this post is ready for some editorial wrap-ups, I can feel free to wander the streets of Dublin again before my flight back home and another week of work. Before taking my 313th flight (yes, I’ve counted the total number of flights I’ve been on in my life. Everyone needs a hobby!), I’ll pop over to the Porterhouse brewery to enjoy some Irish music and a final pint, knowing that I’ve crafted a decent post to self-validate my incessant need for travelling. But while there’s still free wi-fi, I might look into the weekend flight prices to Prague in the autumn, as I’ve heard that Czech beer (and sightseeing) is divine!

In the first blog post, I gave an overview of the definition of style and how this concept relates to how we should think about doing science. Now after some philosophical discussions as of late with colleagues and after a morning spent pondering over this article by 538 about p-values, retractions, and how science is a lot harder than we usually give it credit for, I wanted to take the time to go back to giving a definition to the first part of 'Science with Style'.

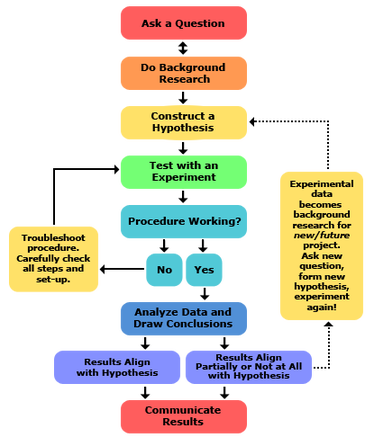

We should not only think about and define the components of 'Science with Style' but we should also think about what getting a Ph.D. really means. Is it a degree of ‘Phinally done’ (as my UF alumni bumper sticker says) or ‘Phucking Do it’ (as your advisor might say) or ‘Piled higher and Deeper’ (as Jorge Cham says)? No, because the Ph stands for ‘philosophy’, and earning a Ph.D. means you shouldn’t just be an expert at pipetting or counting cells, you should be an expert in being a scientist . So what does the dictionary say about science? Science, noun: ‘The intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.’ Breaking down this definition piece by piece, we can see that science is meant to be more than just doing science. We can spend all our time in the lab generating data the rest of our lives and endless hours pouring over endless spreadsheets of results, playing with variables and looking for every possible combination of factors to tell us the meaning of the universe. As graduate students and post-docs especially, we spend a lot of our time as scientists-in-training doing science, but is that the same as being a scientist? Part 1: ‘The intellectual and practical activity’ Graduate students and post-docs likely understand all too well the ‘practical activities’ that go into science. Although perhaps it’s a different issue of whether you want to call trudging to the lab at midnight on Christmas Eve to collect 12-hour time point samples or renting a 4X4 so you can drive to the middle of bear country to collect water samples ‘practical’ or not. In the early parts of our careers as scientists, our lives are dominated by the practical activities: rats to dissect, seeds to count, cells to split, livers to grind, surveys to conduct, field sites to map, machines to fix, data to normalize/analyze/synthesize/everything-ize. To non-scientists, and to many of us scientists that got interested in exploring the natural world at a young age, this is what science looks like, the clips they show on TV and movies of scientists making genetically engineered dinosaurs or solving crimes with fingernail clippings. But the problem is that this is only half of what science is defined as, and only half of what science actually is. Especially as young scientists, busy with all of the practical tasks required to graduate or publish or get out of the lab by 9pm, it’s easy to forget about the intellectual side of science. There’s a reason for those 12-hour time points and water samples from bear country: you’re setting out to answer a key scientific question in order to address a specific hypothesis. Most of the time, especially in graduate school, this question and hypothesis wasn’t first crafted by you, but rather is part of a large grant your PI received or is related to some data that a previous student/post-doc collected 5 years ago in your lab. You’re expected as students to know the reason why you’re doing what you’re doing, but for most students you weren’t a part of the brainstorming and data analysis sessions that went into crafting your project. At the same time your PI is likely balancing other students’ projects and thinking ahead to other grants and collaborations, and may at some point have forgotten that afternoon sitting in their office when they came up with the brilliant idea that is your project. This doesn’t mean that you’re doomed to some irrelevant project from years-old data or some idea your PI came up with in a caffeine-fueled brainstorming session that they happened to end up getting money for. As a scientist-in-training, your training includes both the intellectual and the practical sides of science, so you should focus on both of them. Do what you need to do in the lab, but before you run off to collect that 12-hour time point, go back to the beginning and think about the greater why of that time point: - Go back to the literature related to your project. And don’t just read the papers, think about how they did the experiments, the statistics and conclusions that came out of them, and whether what they say they found is what they actually found. Read not just for facts but to synthesize what’s been done before and how it all connects. - Approach everything you see with your own logic and let yourself see the data without the author’s or your PI's interpretation. Look at everything at a critical angle before you accept it as a (potential) truth. Science was made for cynics, not optimists, so take everything you find with a grain of salt! - After you get a handle on the literature, do an afternoon brainstorming session of your own. Where are the gaps in knowledge? What was observed that couldn’t be explained? Where is there a question that’s been left unanswered? This may not look like science to you or to most people who think of TV and movie science, but this is where the difference between doing science and being a scientist lies. And how we go about being a scientists and answering these unanswered questions lies within the scientific method. Part 2: The ‘systematic study’ At some point when your primary school teacher was getting your class ready to come up with a science fair project, you probably had a diagram similar to this hanging up somewhere in your classroom. This one comes from a science fair project website and just because it was made for 13-year olds doesn’t mean you shouldn’t print it off immediately and hang it in your office:

At some point the scientific method was probably covered again during your undergraduate studies, maybe even in more than one of your courses. This all likely seemed too easy and common sense when you were 13, and your brain was soon filled with more important details like chemical reactions and math equations and the entire Krebs cycle. The issue is when we get so bogged down with the practical parts of science that we forget about the common sense/intellectual parts of science. It’s easy to get lost in the details and the experiments that you have to run to get data, but if you don’t understand why you’re doing what you’re doing, you’ll end up flailing away in the lab running a thousand different assays without any clue as to where the meaningful answers are.

The scientific method may be common knowledge when you look at it, even 13-year olds can get the gist of it, but we can’t push it aside or think that the details are the only thing that matter. The scientific method is the heart and the core of science as a field of study. It’s what makes science science, a field of study where we are trying to figure out ‘the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world. ’ We do this not just by banging our heads against the wall or coming up with things out of thin air, but with a systematic study that we follow for every single thing that we do, if we are to call ourselves scientists. But when bogged down with the details and practicalities of science, where do we start in order to make progress towards making sense of the world? We go back to the beginning, once again: We ask a question. Part 3: ‘Observation and experiment’ Look back at the start of the scientific method diagram. Where does it begin? With a question about why you’ve seen something. In the case of your work, what you ‘see’ is what the literature in your field has told you already. What did someone find but couldn’t explain with what was already known? That’s what you’re setting out to do: to explain something that’s currently unknown. The observation part is what we do to understand what’s known and to help us ask a good question. The experiment is what we do to understand what’s not known and the work you do will lead you to an answer. And it’s not a good answer or a bad answer, it’s just an answer to your specific question. While you can debate on the relevance of 1100+ significant p-values in 538’s article (perhaps there should be a multiple testing correction added into the widget), the take-home message in regards to science is this: The key part of science isn’t in finding good answers, but in asking good questions. You can play around with variables and experimental designs and will likely find different results every time. There’s a million ways to find an answer, and changes in policies and ideas about science are indicative of this: eggs are good, eggs are bad, don’t eat carbs after midnight, carbs don’t matter, Pluto is a planet, no it’s not. But what’s at the crux of science isn’t the answers, it’s the questions. And when you ask good questions, the answers you get back (regardless of what they are) are the meaningful ones that withstand the test of time and replication. So whether you just desperately want to be 'Phinally Done' or are setting out to 'Phucking Do it' or feel like you're always 'Piled higher and Deeper', remember that what you're towards is becoming a Doctor in Philosophy, and that a Ph.D. is not just about doing good science but in becoming a great scientist. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed