It’s never a good sign when your day starts with over 200 unread Whatsapp messages. Last Friday (June 24th), I woke up to news that I and my friends on the Liverpool Whatsapp group had thought would never happen: the UK had voted to leave the EU. Even after the initial whirwind round of messages sent in the early morning hours, the rest of the day was spent reading news articles and seeing the shock and disappointment from UK and European friends on Facebook and Twitter. With the flood of posts swirling around in the past few days, I wanted to take the time and think about what Brexit will mean in the context of the type of work that binds me and many of my UK and European friends together: science.

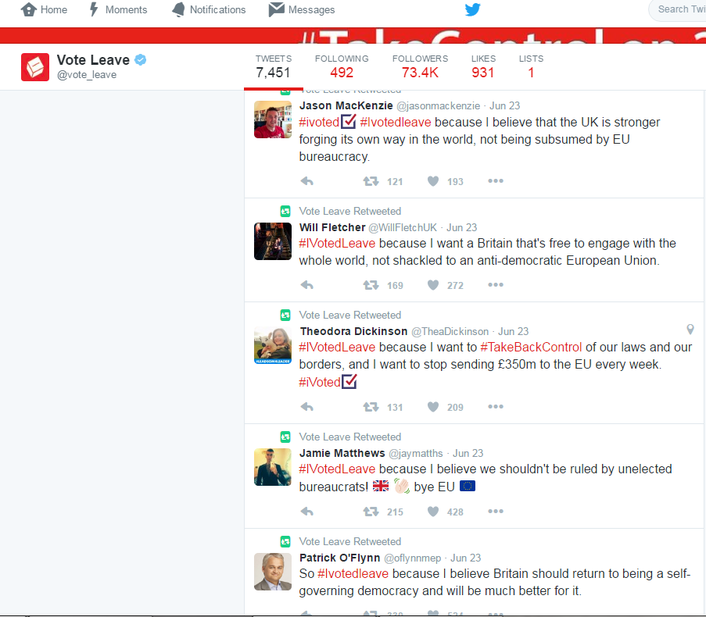

There will be numerous direct effects of leaving the EU on science here in the UK, on everything from the availability of grants, the mobility of professional researchers, and the scientific infrastructure that’s been set up within the EU. As I read these articles and numerous other ones like them, I empathize with my friends who are in the process of developing their own careers in science here. How can you manage additional uncertainties in a field where you already have to spend so much time worrying about grants, short-term contracts, and competitive jobs? The flood of news articles and opinions continued to pour in over the weekend from experts and scientists, but after being drained of my productivity on Friday and worrying about the implications of Brexit on my own future, I took a break from reading the news this weekend. Even so, one of the article subtitles kept me pondering the rest of the weekend: ‘What has the EU ever done for us?’ This question brought me back to the Life of Brian scene, where while planning an uprising against the oppressive Roman regime, the question is brought up of what, exactly, the Romans ever did for us. “... but apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order... what have the Romans done for us?” Romans have now come to mind a second time on our blog and for good reason. During my travels around Europe, I’ve been able to visit 16 of the other 27 EU countries, and only 9 of the 28 EU countries (still counting the UK) were never a part of the Roman Empire. In the many places I’ve visited around Europe, I’ve seen enduring remnants of Roman building projects. From the state history museum in Budapest, full of Roman artifacts found across the Hungarian plains, to the impressive and fully intact aqueduct of Segovia, and Hadrian’s Wall just a couple of hour’s drive from Liverpool, stretching across Northern England and still marking the boundary between what was Rome and what was the rest of the world. Rome was certainly not a perfect empire, but it was one that lasted for over 300 years. This is impressive for a relatively unconnected world as compared to ours, in a time without telecommunications or any transport more rapid than the horse. Even still, Rome was connected across the vast amount of land between its borders, and people were Roman despite where they had been born, what language they spoke, or how exactly they came to be incorporated into the Empire. While I’m sure not everyone had a fantastic life under Roman rule, and there were certainly a fair share of bad emperors throughout the history of the Empire, Rome as a unified concept did mean something important. As a person living in the classical period and regardless of your income or your social status, you would have been able to see the positive impact that a road or clean water had on your life. You would have enjoyed plays in the local amphitheater or the wines and exotic foods more easily available to you and your family from across the empire. You would have felt some protection at being part of a bigger unified nation than when isolated to just your village or your tribe. Being Roman 2000 years ago would have meant being part of something powerful, something beneficial, and something enduring. But as we already know, Rome didn’t last forever. The empire fell and the Western world left with warring neighbors, short-lived empires, and a period in history that came to be known as the Dark Ages. I don’t believe we’re headed for another dark age, but as history shows us we do need to recognize that history involves cycles of uprisings. But unlike the Dark Ages, we have countless sources of news nowadays, we can get facts and figures from reputable sources, and we can hear directly from experts in order to get a better understanding of the problem using sound logic and reason. Right? As we discussed in our storytelling post two weeks ago people tend to rely on emotions when making decisions. With money, a family, and a future on the line, people are not always driven by logic, facts, and figures. We are driven by emotions, by stories, and by selfish needs. Unfortunately, the Leave campaign made good use emotions and fed off the enthusiasm of an uprising, bringing together a rousing rally against ‘the man’ (e.g., the EU) that’s apparently holding us back. This line of campaigning is evident from the tweets on their twitter account and you can see a few of the tweets below:

Oddly enough, there’s no equivalent @Vote_Remain Twitter account, and while there are a flurry of #Remain tweets (especially now after the vote is over), it seems that the question of ‘What did the EU ever do for us?’ wasn’t as enthusiastically addressed by the Remain campaign.

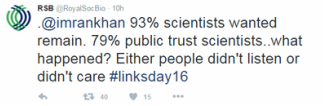

But what does this all mean for scientists? In the midst of worrying about the future of our research contracts, the prospects of losing future EU grants, and thinking our colleagues who come from every side of the world to work in the UK, we also have to recognize that in this day in age, scientists are considered ‘the man’. In a campaign that has won by fueling disregard and mistrust in ‘experts’, is it any surprise that people started to go against the recommendations of said experts? Scientists are not considered to be of a trustworthy profession, and we come off as competent but not very warm. In a recent study conducted in the UK, one person relayed this comment on why they had no interest in science: “Snobs, know it all! Better than others just because they are intelligent, boring and thinking everyone should know what they know!”. Is it then any wonder that in an age where people are taking a stand against the status quo and ‘the man’ that this also means a stand against science? If scientists want to stop being ‘the man’ that the rest of the world is up against, we need to think about and engage in the communication streams that people get. While most of the other respondents did have a general interest in science, many felt that scientists were hard to access. Events like science fairs and festivals look great on paper or on a resume, but many folks are limited in their ability or interest to take time from their own lives on a busy weekend to go and do such an activity. Many are engaged with science news in the media, but since the media also has the potential to get something wrong or to over-sensationalize something, how can we as scientists do better to share our science? If people feel like we are hard to communicate with unless we come to them in a science fair, why should we expect them to trust us as the experts when we say to them from afar ‘if you do X then Y will happen, so you shouldn’t do X’. Now is a good time to reflect on how we as scientists can do a better job at not being seen as ‘the man’ but as a member of this team, of the metaphorical Rome that is our world. Based on the results of this survey, it’s not that people have no interest in science or don’t see value in what we do, but that we’re not meeting people where they are, that we’re still stuck in ivory towers pondering all our expert opinions instead of meeting them face to face. We can spend our days post-Brexit worrying about our own grants and jobs, or blaming the other side for whatever happens next, but in a few years’ time the dust will settle on the UK’s exit from the EU, and we’ll still be ‘the man’. If we focus on getting people on our side by talking with them eye-to-eye and making them part of a two-way discussion, we can make sure that we narrow the gap between The People and The Experts. If we meet with and have discussions with people outside the ivory tower, if we engage in listening instead of lectures, we can make connections and we can build trust. Regardless of the future of the EU, the UK, and everywhere in between, we as scientists still continue to have the power to make great and positive changes in our world. Just because history tends to repeat itself, it doesn’t mean we have to repeat it completely. We can learn from how to connect with people by listening to what fuels their interests and where they want to engage with us. We can change the personal of scientists from being cold-hearted and nerdy towards a more accurate depiction: we are hard-working, motivated, and we are here to make the world a better place for everyone. Despite the turbulent times that we find ourselves in, I am encouraged by the fact that people do have an interest and are looking for information when they make decisions about their lives. And if history teaches us anything, it’s that even though Rome eventually fell, after the Dark Ages came the Renaissance. After having seen first-hand the relics of Rome spread across so many countries, I’m encouraged and hopeful that the relics of a united Europe and a united world will last well beyond our lifetimes. SPQR!

I landed in Marrakech last Tuesday an hour late due to delays in Manchester, and even though I was a bit tired, I was excited to start exploring a new city. After an interesting taxi ride through narrow streets full of vendors, donkeys, and an endless flow of mopeds, I made it to my Airbnb riad (the term for a traditional Moroccan house). I was given a map and some instructions about the best way to get to the city center, just 15 minutes away. I set out into the warm Moroccan evening and soon ended up going the completely wrong way, not even sure which street was mine when I tried to retrace my steps. After accidentally running into the friend of my host who’d helped me get to the riad from the taxi drop-off in the first place, we walked together to the city center, with my enthusiasm for exploring soon turning into embarrassment at getting lost.

With my friends arriving in the morning, I wondered how the rest of the trip would go from here. Would I keep getting lost, and this time run into someone less friendly than the friend of our host? How would the rest of the trip go if we couldn’t even find our way around town? After that initial bump in the road that left me feeling anxious for the rest of the trip, I’m glad that the rest of my time in Marrakech was amazing. I soon found that the best way to get around wasn’t to have a precise plan as to what cross-streets you were going to take, but it was simply to wander through souks and side streets with a vague impression of the cardinal direction you wanted to get to. This approach led to more than a few wrong turns, but it also led to less crowded streets and shops, beautiful street art and wall decorations, and the feeling like you were really getting to see the heart of the city. The trip to Marrakech was a great experience for many reasons, not because everything went to plan, but because it was an adventure in itself: a chance to try new foods and experience new smells, to be a bit unsure of what exactly you were walking into, a time to wander and find things you never expected, and even at times a chance to fail. Whether it was museums that were closed due to Ramadan or dead ends or a store owner rather aggressively trying to sell you a henna tattoos, there were certainly things on the trip that didn’t go all the way according to plan. In the end, we found out things that work and things that don’t and kept going past the small missteps as they came. Throughout our time studying, from primary school to our undergraduate careers, we are taught how to achieve and how to succeed, and we are encouraged to do so. We get rewards for performing above the mark, we get grades and rankings based on our achievements in classes and on exams, and we’re measured on a regular basis in terms of how we succeed and how much we know. Then when you get to graduate school and find yourself in a research-oriented career, the game changes. There are no more exams, grades, or rewards of knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Grad school and life as a researcher is more about producing reliable data, generating results related to a question, and making sense of new information and putting abstract concepts together. It requires a different mindset from the one that gets you success in school: a mindset that includes being ready to fail. If you’re a PI in the US, the success rate for applications on research grants hovers around 20%, and here in the UK it’s closer to 30%. That means on average you’ve got a higher percentage chance of failing for every grant you apply for-and if you’ve never applied for a grant, it’s definitely not a small endeavor. In addition to the task of securing research funds, as scientists we’re also met with experiments that fail, manuscripts that get rejected, uncertainty in terms of a job market or a long-term contract, and criticism everywhere from your PI to people who come to your conference presentations. It’s a really difficult transition, especially for those of you for whom primary school and/or undergrad came easy, who might be naturally good at memorizing facts or taking tests but who find research more of a challenge than initially expected. But this post isn’t meant to paint research as a life of doom and gloom, of spending your days steeped in failure. I’ve met lots of colleagues who’ve been turned down for grants, but because they knew the idea was a good one and believed in the value of the project, they learned from the first round reviews and had a revised application accepted in a second or third submission. I’ve seen friends struggle in the lab for weeks or months on end, then followed by strings of incredible results that just keep rolling in. I’ve read about the hurdles that world-famous scientists had to go through or the challenges they faced in their ideas or in their careers, only to come back from a challenge with more vigor and an even better understanding of the problem than before. In one of our previous posts from last year we talked about the importance of not being afraid to fail, a post inspired from my time spent in martial arts. But it’s one thing to say ‘don’t be afraid to fail’ and another to actually follow through with putting yourself at risk for failure. How can we become better at taking that first step, knowing that after a few more steps we might easily fail at our task? As a child and through my studies as an undergraduate, I seemed to be good at all the things I participated in. But it wasn’t because I was good at everything; in fact, I was very bad at trying new things, because I was afraid of failing. I was good at the things I did because I avoided things I was bad at, whether it be team sports, dating, socializing, or getting lost. In graduate school, I learned how to fail the hard way: I took failed experiments and rejected papers really hard, but at the same time grad school became one of the most enlightening times in my life. While I was learning how to fail the hard way, I also figured out how to be braver at venturing out into unknown territories of research and of life, and I learned how to fail in a way that didn’t make me feel like I had done something wrong. But how exactly does one become good at failing? Remember that failure is part of the process. Research is difficult because you are working on the cutting edge that divides what’s known and what’s yet to be discovered. You’re not repeating the same thing that any one person has done before, so because you’re in uncharted territory there will inevitably be wrinkles to sort out and things that don’t pan out the first or fifth time around. The famous scientists that came before us also made mistakes, sometimes even a lot of mistakes, but they also know that it’s all a part of the scientific method: you have an idea, you test it, and then you figure out whether it’s right or wrong. Science isn’t about always being right, it’s about figuring out the answer, whatever that answer might be. Work on achieving a balance of optimism and pessimism. Being too much of an optimist can leave you feeling like you’ve taken a hard hit when something doesn’t work, because you’ll have gotten yourself excited about an idea or an experiment. In contrast, being too much of a pessimist and thinking that every upcoming experiment will fail can leave you feeling too unmotivated to even try. A good scientist is a balance between the two: you recognize that not everything will be sunshine and roses the first time around, but you also are inspired and hopeful for good results to come down the line. As with other times in our career when we need to achieve a balance between two sides of a coin, you can also work on achieving this balance by surrounding yourself with colleagues who might lean more towards one side of the optimism/pessimism spectrum than you do. Lower your expectations. This sounds like a terrible piece of advice, but especially if you’ve achieved a good balance between optimism and pessimism, having lowered expectations can come in handy. If you over-exert yourself by trying to get everything to work all at once or are relying on one success to raise you to another, one failure can knock you over. Take your research one step at a time and leave a buffer in terms of time and energy by taking into account that some things might not succeed. Don’t expect that something will work the first time around, and if instead you expect that you won’t get perfect results right away then you’ll know to leave some time to repeat things as needed. On the other side of the coin, lowering your expectations also means you have an excuse to celebrate the small successes. In grad school especially, it’s these small victories that can help keep you going. Had a PCR reaction work? Drinks with your lab! Got a paper that wasn’t rejected outright? Drinks with your lab! Celebrating these smaller, perhaps ‘lesser’ victories will make the bigger ones seem even more incredible and will keep you going until things start to go your way more consistently. Come at a problem with confidence, even if you don’t feel confident. This week in tae kwon do, a few other students are getting ready for testing. Our instructor was giving all of us a pep talk after one prospective red tag to red belt was clearly uncertain and nervous during practice, saying that we needed to be confident and ready even when we didn’t know everything 100%. Even the most veteran black belt will get nervous when faced with a belt testing, and it’s easy to believe we’re not doing everything perfectly, that we’ll make a mistake, or that we’ll forget something. In a recent seminar I gave on the five easy steps for a perfect presentation strategy, I asked the participants what they were afraid of the most while giving a talk, and most said they were afraid of doing something wrong. I thought back to those replies during tae kwon do class this week, and realized again just how much martial arts can teach us about being a scientist: it inspires us to live a life of confidence even in the face of punches and stern instructors (or professors) grading our every move. When faced with fear, you meet it with ferocity. When afraid of failure, you hold yourself with the confidence of a person who knows everything like the back of your hand. It’s about being ready to face a potential for failure in the same way you face the potential to succeed. Envisioning success is half of the battle, and by facing potential failures with confidence you can increase your chances of success. Don’t let a failure (or two) define you. I still get nervous for talks, tae kwon do testings, even conference calls. Before anything that makes me feel nervous, I always end up giving myself the same pep talk. I tell myself that no matter what the results are, it doesn’t change who I am. Just like the two failed black belt pre-testings that didn’t keep me from getting a black belt later on, or the many failed experiments or rejected papers that didn’t keep me from getting great data or publishing my results. What’s more important than not failing is to learn something from the moments when we fail, to celebrate when we succeed, and to not be afraid to let a couple of mistakes hold us back from getting where we want to be. Whether that’s a government lab researcher, a university professor, or the CEO of a company, the failures we have along the way won’t define how we get to the end result, and won’t solidify our fate or who we are as people. Failure is an option in science-and more than that, it’s a way that we make progress. It doesn’t have to feel like banging your head against a wall if you look at failure as part of the process instead of blaming your own faults. By approaching problems with confidence, holding back from becoming too over-zealous when it comes to thinking what might work or not, and by not letting each wrong turns define who we are and where we go, we can learn how to use failure to our advantage, and to become better scientists and people in the process.

Last week I heard a great podcast news report about the way we talk about scientists and how that can inspire (or intimidate) those in the next generation and affect their desire to become scientists. In the US, we tend to talk about scientists as being geniuses, as having brilliant ideas and doing groundbreaking work that’s changed the course of our lives. But apparently that’s not a good way to motivate children to pursue science as a career path. Talking about scientists like they are super-human geniuses causes children to believe that since they aren’t geniuses, they’re not cut out for science. This is in contrast to how the stories of scientists are told in China, where the focus is on hard work. The podcast also describes a study in which kids were told stories about scientists in the context of being geniuses, in the context of personal struggle/hard work, and even in the context of having to ask colleagues for help when they were stuck. The kids who were told the ‘struggle’ stories were not only more engaged with science activities in the classroom, they even performed better on science tests.

The results of this study fascinated me throughout the week. Just by talking differently about scientists, about ourselves, we can motivate students not only to become more interested in science, but even to do better in exams. By relating how great scientists also faced challenges and persevered, children recognize the need for hard-work and determination and won’t give up if they find they are not as brilliant as Einstein. This study also got me thinking about stories as a whole. Science communication is essentially about telling a story with impact, to motivate and inspire…but as scientists, are we equipped to be able to tell these types of stories? As an undergraduate in Environmental Studies, my formal training in writing was, well, very formal. We had a specialized course for students in the biological sciences, and if you were going to be an engineer or a banker you were in a different technical writing class. While these courses were clearly designed as an introduction to what writing would look like for the jobs we would end up in, I wonder in hindsight if this is the wrong way to go about a formalized training in how to write. Yes, as scientists we need to know how to talk about p-values, how to structure a manuscript, and how to write an abstract, but this type of knowledge seems to come as easily through practice as it does through formal, classroom-based training. What is more of a challenge is for us to figure out how to talk to people outside of science, given that we spend so much of our time since undergrad learning how to talk with ourselves. Could this be the block between science and the public: simply an issue of not knowing how to tell a story in the classic way because we’re only trained to talk to ourselves? In contrast to being trained as a scientist, if you did your undergraduate in marketing you’d be thoroughly trained in how to tell a story, in this sense with the goal of leaving a lasting impression on someone, an impression so strong that they might even be biased towards buying the product or service you’re selling. One way that marketers do this is by using stories, and marketers do this for a reason: stories are a means to connect with emotions, and if you connect with the emotions of a person, you can create a more memorable connection. Whether it’s an ad about a horse and a dog who are best friends or a simple ‘We lived’ following a close-up of car crash wreckage, the ads with memorable content are the ones that impact our buying decisions, which are usually driven by emotion instead of logic. Another example of the impact of stories can be found in (name of teacher’s) marketing classroom. She asked each student to make a one-minute pitch for an imaginary product. Nine out of ten students presented facts and figures to make their case, but one student told a story about the product. When the audience was asked to remember things from the ten pitches, 5% could recall a specific figure or statistic, but 63% of them remembered the story. When someone tells you a story, they are also directing your brain’s activity. If you read or listen to a story of someone running or jumping, versus just being read a list of words with no context, your brain visualizes the actions, and activates the same ‘motor planning’ brain regions that are used when you get ready to do a physical activity yourself. In comparison, the words in isolation or outside the context of a story simply activate the language processing center of a brain. Think for a moment about reading a scientific paper versus an action-adventure novel: in the novel you can empathize and represent the activity, but can you do the same thing when all you have are facts, figures, and abstract concepts? So what do these examples from marketing and psychology mean for scientists? Early on in our careers, we’re trained to write very technically, to sound like a scientist, to talk about our work in the context of figures, error bars, statistical significance, and developing logical conclusions that fall within the bounds of our results. This is how science works: we’re presented with a hypothesis, we address that hypothesis with experiments, and we come to a conclusion about the state of the universe from those results. But at the same time, we are also human beings, as are our colleagues, our collaborators, and all the members of the public that fund our research in one way or another. Our brains are hard-wired to understand and be moved by stories, and while we’re trained to trust statistics and plots, we can still be swayed by the powerful emotions of empathy, joy, sadness, and fear. But we can’t just tell scientists to go out there and tell stories, because science stories are not the same as the ones from marketing, literature, or art. Our stories aren’t here to entertain or to entertain or to sell a product, but are rather a means of working towards an understanding of how life, the universe, and everything in between works. It’s unfair to trivialize our hard-work using the foundations of the scientific method using sensationalism and fear-mongering, but it doesn’t mean that scientists can’t be storytellers, too. In previous posts we’ve touched a bit on methods and approaches for writing and how you can frame your manuscript as a problem and solution approach. In the context of storytelling, you can think of your research as something akin to a mystery novel: you present some ‘case’ that needs to be solved, you describe your method for cracking the case, and present to the reader your conclusions as to who-done-it. Other options include presenting your science story with some relevant background (i.e. why the research happened) followed by the consequences of your work (why it matters). These approaches have also been formally adopted in materials developed for schools, with the aims of telling stories about scientists as a way to motivate and inspire them to get involved in science. A quote from one of this article: “Scientific storytelling, as it relates to teaching and education, should engage the audience and help them ask questions about the science: Why did this happen? What would we do next? How is this possible?" So while there is some dialogue about how to tell these stories, especially for educators, how can we as scientists, more fully embrace the power of storytelling in our own work? Interestingly enough, if you search for ‘how to tell a story’ versus ‘how to write a scientific manuscript’, you’ll come up with very different results. This one from Forbes is a simple list of to do’s that also echoes what we’ve touched on in our Five Easy* Steps presentation posts. In contrast, the ‘scientific manuscript’ guidelines are more guidelines for structure and less for impact, for example in what order to write the introduction versus the materials and methods. These are helpful guidelines in the context of the science side, but what about the storytelling side? How can we connect storytelling to science? While there are a few websites with some pointers on how to tell stories, here are a few other considerations to keep in mind: Don’t tell people something is important: make them believe it. Instead of telling your reader that your research is great and then give them a list of reasons why, describe for them the world in which your research sits. Paint the picture of what your field looks like and how your research fits into it. People, scientists included, will not instantly respond to being told that something is important, we need to realize for ourselves that it’s important and develop some connection to the problem. Hook your readers in with a story about what your world (of research) looks like. What are the mysteries still unsolved? What have people worked to figure out but in vain have yet to find an answer to? What will happen if nothing gets done? This isn’t about telling lies to make your work seem more important, or in foregoing facts for sensationalism, but focuses on presenting why people should care instead of just telling them to do so. If people remember one thing, what should it be? Regardless of whether it’s a manuscript, a blog post, an email, or an oral presentation, people will forget things. Details will get lost in the numerous other details you present, they might lose attention, or you might just be giving them too much information at once. Think of what your big-picture take-home message is, and make sure that gets across. Put it in your abstract, at the end of your introduction, at the beginning of your discussion, and at the end of your conclusion. Tell your readers again and again what you want them to remember, and you’ll ensure that portion at least sticks with them. Write what you want to read. As scientists we’ve been trained to write in a certain way-but that style is primarily focused on structure, not content. These are the sections you should include, these are how you transition from introduction to methods, etc. The structure is important and should be kept, but it’s not the only tool we can use as writers. Use the advice from writers and from advertisers in terms of crafting the story and the vocabulary you use. As long as the science is there, using approaches from other fields is a valid way of setting up your paragraphs and structuring your sentences. If you don’t like reading papers that drone on about ‘therefore, XYZ’ and ‘henceforth, ABC’, then don’t write those papers. Say what you found, what it means, and why it’s important in the context of your story, and be simple and clear about how you got to the conclusion you did. Read stories by good writers. We’ve already touched on this recommendation in other posts, and there’s a reason we mention it again. We generate a lot of our vocabulary and the way we talk from the people around us. If you spend time with someone that says ‘like’ or ‘totally’ a lot, you’ll totally, like, pick up on it, too. The same goes for writing: if you read what good writers write, it helps you do the same. You pick up on examples of how to transition between ideas, what words or phrases are memorable, and what analogies are helpful for conveying a message. While there are examples of good writing in the scientific literature, take a break from science reading and explore some blogs, news articles, or books whose focus is a story in order to get some insights into how to tell your own. Write something other than science. It’s hard to put into practice narrative or story-based writing if you keep writing using the same structure you’ve done before already. Try expanding your writing repertoire by penning a creative short story or a news article instead. See how it feels to write something when logic isn’t at the forefront. How do you convey a complex topic? How do you transition between complex ideas? Practice how you can connect words and ideas which aren’t driven by science and then take those lessons into your own science writing efforts. Thankfully, we have a lot of great science storytellers to learn from. If you want to get inspired, be sure to check out the works of Carl Sagan and Steven Johnson. In the next couple of weeks we’ll be doing a book review on Modern Poisons, a lay person’s guide to toxicology, with some insights on how to write a science book for a non-scientific audience from the author (and my former undergrad honors thesis advisor) Alan Kolok. And they communicated their science happily ever after. THE END

It’s finally the end of the semester! Time to put your textbooks away, apply some sunscreen, and get ready for a summer of…science? Your summers spent as an undergrad and your summers as a grad student (and all the subsequent summers you’ll spend as a researcher) will look very different from one another. Even though it’s been 7 years since I finished my undergraduate studies, I still feel nostalgic and a bit jealous when I see droves of undergrads heading home after finishing their spring term exams, off for that blissful time when you’ve accomplished another year of studies and have an entire summer ahead to enjoy life before it all begins again in the fall.

Life as a researcher can certainly leave you feeling like you need your own summer vacation. It’s additionally difficult when working in an academic setting, where you witness the happy undergrads set off on summer adventures while you’re stuck in the lab. Regardless of whatever stage in your career you’re in, summer can still be a great time in the year of a researcher. Summer provides us a bit of warm air to freshen our spirits and plenty of sunshine to brighten and motivate us. It’s also generally a less busy time of the year regardless of what field or what sector you’re in, as most folks will head off on vacation when kids are out of school or to take advantage of the nicer weather for some needed rest and relaxation. As with most things in life, having a good plan is a great way to make the most of it. Summer can be a great chance to unwind and relax after a busy academic year, but it’s also an opportunity to re-focus and re-assess where you are and what you need to do to make progress in your own project, while also thinking about where you and your career will go next. Especially for those of you who are just starting grad school and experiencing your first ‘academic’ summer, it’s important to see how this part of the year will look like, what you can expect from the people you’ll work with, and how to make the most of your summer months. Summers are a great time to explore some ideas of your own and to develop your skills of working more independently. And while summer is a good opportunity for you to take your own summer vacation, be careful not to use it as an excuse to do no work at all. Remember that part of the training in grad school is to become an independent researcher, so just because your advisor’s not around doesn’t mean you necessarily should take off, too! Plan ahead for the summer. Whether you’re at a university or an industry research lab, people tend to disappear over the summer. Between school vacation for kids, fieldwork, conferences, and the fact that everyone else is on vacation, you may soon find yourself in an empty lab. If you have things you need done by other people during the summer months, or need to get feedback on something from a committee member, professor, or collaborator, be sure to keep in touch with them early on in the start of summer and find out when they’ll be out of town. Don’t put yourself in a position to be set back in your own project just because one of your collaborators is spending 2 weeks away! Spend some time on your own projects or goals. Summer is a great time to focus on the things that you haven’t managed to get done or that might not have been a priority during the regular academic year. Have a small side project or experiment that you’ve been dying to try but haven’t had the time? Set aside some time in the summer months to focus on getting it done. Doing these smaller projects can also keep you motivated during the quieter part of the year, especially if you are the type of person that thrives on always having something to do. You can also expand your idea of a ‘side project’ to include new activities like outreach, volunteering, and mentoring. Want to get involved in some public engagement? There are always ample opportunities for activities with schools and summer programs, and it’s a great time to try something new like talking to 7th graders about science. Has your PI talked about setting up a lab twitter or Facebook page but never got around to it? Sign up for an account and work on developing your group’s social media presence over the summer, then come the start of the semester you’ll have a fully up-and-running platform to build from. These activities can also bolster your CV and give some breadth to your current work and research perspectives. Practice becoming an independent researcher. It may be easy to lose sight of goals when there is no one around to witness your hard work or tell you what to do. Regardless of what sector you end up in, though, you’ll be required to work independently as a part of it, and you’ll be expected to take initiative instead of always waiting to be told what to do next. If your PI or other collaborators are gone for some time, use the opportunity to work things out on your own and to try out some new approaches to answering a problem. It will show your PI that you’re working on developing your own independent research skillset and will also give you some hands-on experience in how to manage your own time and efforts. While doing so, keep tabs on yourself and your productivity levels during a day. Be sure to also keep in touch and report back to your PI on a regular basis when possible, which will allow you to get feedback on your independent research endeavors and to figure out what works and what doesn’t. Think about what you want the rest of the year to look like. One way that you can work on becoming a better independent researcher is to do some long-range planning of your own. It can be hard to think of what the next year or two will look like when you’re busy trying to get things done during the busy academic year, and the summer can offer a brief respite for your schedule to think about where you are and where you want to (and need to) go next. Take some time to think about what data you have, what questions you’ve addressed, which ones have arisen because of your work, and what you need to do to have a complete story by the end of your project. Doing this thinking exercise can give you some perspective on what you’ve done already and can put you in a better position to do great work during the next year to be in a position where you’ll have a lot to show, be it a manuscript, a dissertation, or a job! Do some summer reading. Whether you get something off the summer best-seller’s list or something that’s been sitting on your shelf for a year, grab a book and make your own summer reading club. Reading something that’s not a scientific paper can be a good break and refresher for your own mind and can offer some perspectives that you don’t as easily get from a TV show or a movie. Added bonus: you can enjoy them outside without worrying about screen glare! On the more scientific side, you can also use the summer to read a few papers that go outside the scope of your normal reading list. Just as picking up a new book can expand your mind and introduce you to new places, reading a paper from another field is a good way to get a fresh look at science as a whole, and it may even bring a few ideas to bring back to your own project. Make some excursions…for writing. Nice weather and relaxed academic schedules are a great opportunity for some excursions from the lab to a new working environment. Take advantage of shorter lines and less noise at your favorite coffee shop to watch the world go by while you work on emails or a manuscript from outside your normal work setting. Summer is a great time of the year to get some writing done and to take some time ‘off’ from the lab and other obligations you have during the regular academic year to work on a paper or make some progress on your dissertation. Summer is also a great time for your advisor to be able to read your work more thoroughly, as fewer obligations for faculty meetings and teaching means they’ll have some time on their hands to help you with a manuscript. Enjoy the sun while it’s there. Remember that not every excursion has to be for work! Take advantage of a sunny afternoon for an afternoon drink with a colleague or a brainstorming/sunbathing session outside. While you should work on not making these excursions too much of a habit, take advantage of a more relaxed working pace and don’t feel guilty for taking some time to recharge and relax. Summer is a great reminder to take life at a slower pace and to enjoy life and work outside of the constant rushing around and fast-pace of the academic year and of research as a whole. There is always plenty of work to do in the lab and for your project, so be sure to enjoy the sun and the slower pace while it lasts. Take your own vacation! There’s a reason that a lot of your colleagues, advisors, and collaborators will take a vacation in the summer: because they need one. We all need a break sometimes, and the hard part about research is that you always feel like there’s something that needs to be done or a pang of guilt when you’re not dedicating all of your time for scientific progress. The fact is that life as a researcher is busy, with months full of grant writing, lab work, classes, conferences, and everything in between. Regardless of whether you did 100% of the things on your to do list, a break in the summer will do you some good. It doesn’t have to be a long vacation, as even a couple of days to get out of town or a day at home to enjoy the sun from the comfort of your own balcony can do wonders to refresh your mind and get your brain re-oriented for the next round of research. Be sure to check out our archives for ways to make the most out of your break time. Regardless of where your summer is spent, be it out in the field counting bugs or in the cool air conditioning debugging code, there’s a lot you can do to make your summer productive and relaxing at the same time. Taking some time to focus on your own interests and professional development, taking the initiative to become more independent, and working on the loose ends on your to do list can set you up for a great summer that will leave you poised for the start of another academic year. At the same time, remember that even though you’re not an undergrad anymore, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get to enjoy some much-needed R&R in the summer months. In terms of our own Science with Style summer itinerary: We are currently getting ready for our first-ever Science with Style seminar this week at the University of Liverpool as part of Post-graduate researcher week! If your UK-based institute or research group is interested in hosting a one-hour seminar on giving scientific presentations, please get in touch and we’d be happy to work with you. We’ve also got quite a long reading list of our own, with a couple of these to be featured in an upcoming book review later on in the summer, in addition to some new posts for our Heroes of Science series. In the meantime, I’m also ready for my own summer break, currently listening to Andalusian music while dreaming of the Moroccan food I’ll get to enjoy in less than a week while I’m sipping mint tea in Marrakech. - Modern Poisons, a contemporary book on toxicology written by my honors thesis advisor Dr. Alan Kolok - Seven brief lessons on physics, because I need a good lesson in physics, be it one or seven of them! - Born for this: How to find the work you were meant to do, intrigued after taking this quiz - Aleph, because it's been sitting on my bedside table since March and because I loved The Alchemist

With one and half days still remaining in the SETAC Nantes meeting, I was exhausted by the lunch hour on Wednesday. I had presented in an early morning session that day, had spent the previous two days in meetings and filming a promo video for the next SETAC science slam, and was dreaming of caffeine on a regular basis. That being said, I did feel good knowing that the next day I had an evening flight to Marseilles for an extended weekend in the south of France. Just then, a text message from RyanAir informed me that my flight was cancelled because of strike actions by air traffic control. It was a bit of a drag, but soon enough I was re-booked for a Friday trip to Perpignan and re-invigorated with the chance of spending a weekend of wine and sun after four days of conference-ing.

Instead of a simple bus ride to the airport to catch my sunshine-bound flight on Friday, I found myself sitting in a taxi queue with less than an hour and a half before my flight left, glancing around the corner every few moments and beginning to feel anxious and desperate, wondering if a taxi would ever appear. With protesters blocking the roads for the airport buses and no taxis in sight for the past 30 minutes, would I ever make it for my long-awaited holiday? Long story short, I didn’t. And after yet another cancelled flight and the prospect that my return flight to Manchester next Monday would also be cancelled because of strikes, I rebooked myself for a direct flight home and spent my long weekend on the Merseyside instead of the Mediterranean. This was the first time that I had to cancel a trip completely, but it was certainly not the first time I’ve felt stuck somewhere and quite anxious because of it. Last week, there was no way for me to call for a cab, no way to unblock roads or un-cancel flights, and only a limited amount of times I could continue to keep booking and re-booking things last-minute. In hindsight I was frustrated with how I felt about the whole thing, since in the grand scheme of things it was just a long weekend away. It also made reflect back on times in grad school and as a post-doc when I was really stuck and on things that were more important than just a weekend in southern France. Whether it was crossing my fingers about a job, advisors that left halfway through a PhD, or even just full days in the lab that went completely wrong, research has a way of making you feel on edge, like so many things are beyond your scope of control. The internal dialogue can get even worse if the situations you find yourself in cause to second guess yourself or your past decisions. Throughout this blog, and also in the way I talk to myself and to my friends, I focus on finding opportunities, developing strategies, and visualizing the potential of life. I do what I can to focus on making bad situations better, and strive to give advice or ideas for getting through the tougher parts of life as a researcher or as a graduate student. But in my own encounters with stress and anxiety, it’s become clear that there isn’t always a strategy for getting out of a bad situation. Sometimes you really are quite stuck, like waiting for a taxi in a city full of protests and road blockades as the minutes count down for your flight leaving without you. In the words of an Italian woman who, when my friend asked her when the bus would arrive since it was already 5 minutes late, replied with a curt ‘It comes when it comes’. It's true in travel as much as it is in life. It may seem like an odd set of advice to tell you what you can do when you can’t do anything, but if you’re like me, when you can’t do anything, you still want to do something. You can’t make the bus or the taxi come on command, but you can make things better for yourself during the wait: - Do something small yet positive for yourself. You may not be able to fix the problem or change your situation right away, but you can still do things to take care of yourself when you’re in a rut. Go for an afternoon jog, do some shopping, read a book instead of a paper, see a movie. These things won’t directly fix anything related to the problem at hand, but taking some time for yourself, regardless of how small it may be, can do wonders to help you relax, even if just for a small amount while stuck in a stressful situation. This is especially true if you focus on things such as beloved personal hobbies or your physical well-being. - Do something for someone else. This may seem counter-intuitive, but being there for other people, whether they be friends or strangers, can help put your own stresses in context. It’s not that their problems are bigger than yours but it’s a reminder that we all have somethings that knock us over now and again, and this provides us some solidarity in realizing that we’re not alone. This can be something very formal such as volunteer work or even something informal, like offering to take a colleague for dinner or a walk after work when you know they are stressed out. Talking to other people can provide some perspective for your own situation, and sometimes a bit of advice about what to do moving forward, and sharing sympathies with another person can help get you out of your own funk that you might be in from feeling stuck. - Don’t keep it to yourself. Even if you think your situation is exclusively unique to your project or your life, don’t feel like you should keep it to yourself. And since you know you won’t be able to distract yourself from thinking about the problem, don’t try to push it to the back of your mind only to have it come up time and time again and wear you down even further. The best way to approach the situation is to articulate it, in whatever medium you feel the most comfortable in. If it’s something more emotional or personal that you want to keep private, write it down somewhere. If it’s something that you want advice or perspective on, talk to someone you respect and trust. In graduate school I kept a small notebook at home; I didn’t use it to write about what I did or what happened that day but instead used it as a way to talk to myself about emotions and frustrations. How you do this will depend on you and how you deal with stress, but however you approach it be sure to articulate what you’re going through and why exactly you feel stuck, stressed, or anxious. - Keep moving. There are ways in which you will be stuck, but don’t get stuck in thinking that you’re perpetually trapped or are stuck in every part of your life. You may not be able to directly solve the problem you’re in at the moment, but there is always something you can do in the meantime. If you’re waiting to hear back on a job or a grant application, keep working on other applications in the meantime. If you had a big experiment that gave results you didn’t expect and you have no clue how to move forward, read a few papers that you didn’t see before and see if you missed something. It won’t be an ideal solution to the problem, and sometimes to keep moving means you have to take the decision to leave a situation entirely, but anything that helps you from feeling slightly un-stuck is a good thing. - Think about the big picture. In the heat of the moment, even a small hurdle can feel like a mountain. As you go through the previous ‘to dos’ in this post, think about the situation you’re in and how it will impact your life a year or even five years from now. Sometimes these are big events that we feel stuck in, but other times they only feel big because we’re right in the middle of them. Think about your long-term goals and how you can get there. Maybe this situation is a giant wall in front of those goals, and maybe it’s just a road blockage on the way to the airport that you can walk around with your luggage in tow. In the situations I’ve been in and have seen others go through, when you have your health, a good support team, and a little bit of drive to keep going, you’ll always there. Wherever there is isn’t always clear, but you’ll always end up somewhere and, more importantly, you won’t be stuck forever. As for me, I’ve been fortunate to have gotten out of a few ‘stuck’ situations fully in-tact, and have seen a fair share of colleagues and friends do the same. Whether it be minor or major, working from small things to big, talking to friends or to yourself about your situation, and looking beyond the immediate situation, there are numerous ways of doing something when you can’t do much else. That being said, if you are in a place where you feel stuck more often than not, or feel like you can’t easily do the things on the list, don’t be afraid to ask for help from someone at your institute, university, or your doctor. There is no reason that anyone in research or graduate school should feel impossibly stuck. There’s always a way forward-even if you end up in Northern England instead of Southern France! |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed