The strategic graduate student

An early career researcher faces a lot of pressures within the academic research environment. We’re expected to work hard and put in long hours on experiments and data analysis, under the idea that more output (or, in our case, more data) will inevitably lead to more papers and more opportunities. Hard work is a crucial aspect of success in graduate school, but what’s sometimes not as clear, especially in the early periods of our research careers, is how to work smart. Working smart means being strategic with time: set goals, plan ahead, and adapt as needed. But how exactly can we learn to become more strategic in our work? It’s one thing to design a flawless plan of experiments and analyses in great detail…but what about when an unexpected results offers new insights or inspires different experiments? With an endless array of tasks, distractions, and the all-enveloping feeling like we have to be doing something at any given point in time, how can we clearly see and decide on the most valuable course of action at any given moment? I’ve been interested in answering this question both in a broad sense as well as for my own work-life balance. And while I’ve had wonderful mentors, coaches, and bosses who have taught me how to prioritize my current work while visualizing the future, I also like to find inspiration from other sources. My reading hobby typically leads me towards history books, in part as a break from reading about science but also as a source of awe-inspiring stories. It’s incredible how often the lives of the great men and women of history were defined by how they made pivotal strategic decisions or how a single idea changed the entire course of history. One of my recent such reads was Robert Greene’s “The 33 Strategies of War”. Greene’s book offers insights on how you can make your own career, or even your entire life, more strategic. The book is interwoven with stories from history highlighting the 33 concepts described in great detail in his book. If you’re not a military history aficionado, there are also a number of stories about politicians, business leaders, and even artists who fought in their own sort of ‘wars’ as they worked to bring their goals and ideas to life. Highlights from “The 33 Strategies of War” Greene’s book is not a practical ‘How to make war’ type of book. It instead focuses more on the psychology of conflict and how to approach these situations with a rational and strategic mind. One of the most important facets of good strategy is to have a wide perspective of your situation. In the case of research, you should thoroughly understand the problems that your field is working to solve and the possible solutions: “To have the power that only strategy can bring, you must be able to elevate yourself above the battlefield, to focus on your long-term objectives, to craft an entire campaign, to get out of the reactive mode that so many battles in life lock you into.” “The essence of strategy is not to carry out a brilliant plan that proceeds in steps: it is to put yourself in situations where you have more options than the enemy does. Instead of grasping at Option A as the single right answer, true strategy is positioning yourself to be able to do A, B, or C depending on the circumstances. This is strategic depth of thinking, as opposed to formulaic thinking.” Greene also stresses the importance of acting on the plans you make while being flexible to changing situations. While strategy is the “art of commanding the entire military operation”, tactics refers to the “skill of forming up the army for battle itself and dealing with the immediate needs of the battlefield.” You can think of strategy as the plans you draw up for the experiments you need complete for your dissertation and tactics as the action you take if you find out that one of those experiments was already done by another lab or is no longer needed because another paper refuted the hypothesis. And regardless of how well you plan, you must also be ready to work hard and to learn from any mistakes you make. As Greene said: “What you know must transfer into action, and action must translate into knowledge.” Greene’s book discusses how to use both victory and defeat to your advantage. Both victory and defeat are temporary, says Greene, because what matters is what you do with the lessons you gain from each encounter. If you win, don’t become blinded by your own success but keep working hard and moving forward. If you lose, envision your loss as a temporary setback and use the lessons learned to plant the seeds of future victory. Greene also talks extensively about the way that emotions can cause you to make ill-informed decisions. This is especially true for academics and young researchers, where the pressures to work hard and publish can lead many to mental health problems or simply finding themselves burned out from exhaustion. Many of the stories in 33 Strategies of War show how people extricated themselves from difficult situations and provide hope for the rest of us that anyone can make it through any type of challenge we might face: “Fear will make you overestimate the enemy and act too defensively. Anger and impatience will draw you into rash actions that will cut off your options.” To become a strategic student, start by waging a war against yourself Greene’s book goes into great detail on the many facets of war, including offensive and defensive tactics as well as methods for psychological warfare. What I found the most resonant, especially for early career researchers, were the discussions around internal warfare: ‘declaring war on yourself’ in order to progress and move forward. Greene also focuses on the importance of self-confidence and having a positive mindset—a topic we discussed earlier this spring. One of the most striking personal stories in this section is about General George S. Patton, the famous WWII general who was instrumental in leading the Allies to victory. But before he was a WWII general, he found himself commanding a small contingent of tanks in France during WWI. At one point his unit ended up trapped, their retreat back to base blocked and the only way forward through enemy lines. He found himself terrified to the point of being unable to move or speak. In the end he was able to muster enough courage and stride forward, but the moment left a mark on Patton. He made a habit of putting himself into dangerous situations more regularly, to face that which he feared in order to become less afraid of the situation. This is one of my favorite stories from 33 Strategies of War. It not only shows us the human side of a great general from modern history, but it also shows us the importance of facing our fears. There are many unknowns, uncertainties, and even fears we face in our own work: what if we get something wrong, what if an experiment fails, what if we don’t win that grant or fellowship. But putting ourselves into challenging situations is part of how we progress. Facing and embracing what we fear helps us move forward and lessens our anxiety surrounding failure. Another important consideration for graduate students and early career researchers is the importance of taking time away from our work. We’ve discussed the importance of breaks and time away from the lab to give us perspective on our work and refresh our minds, and Greene also highlights this as a strategic move: “If you are always advancing, always attacking, always responding to people emotionally, you have no time to gain perspectives.” Through these opening chapters, Greene explores this internal war and how we can develop a warrior’s heart and mindset. Instead of summarizing the chapter in great detail, I’ve highlighted are a few of my favorite quotes from this part of his book: “He (the warrior) must beat off these attacks he delivers against himself, and cast out the doubts born of failure. Forget them, and remember only the lessons to be learned from defeat—they are worth more than from victory” (About your presence of mind): “You must actively resist the emotional pull of the moment, staying decisive, confident, and aggressive no matter what hits you.” (On being mentally prepared for ‘war’): “When a crisis does come, your mind will already be calm and prepared. Once presence of mind becomes a habit, it will never abandon you.” and “The more you have lost your balance, the more you will know about how to right yourself.” (About keeping an open mind): “Clearing your head of everything you thought you knew, even your most cherished ideas, will give you the mental space to be educated by your present experience.” (About self-confidence): “Our greatest weakness is losing heart, doubting ourselves, becoming unnecessarily cautious. Being more careful is not what we need; that is just a screen for our fear of conflict and of making a mistake. What we need is double the resolve—an intensification of confidence.” (On moving forward): “When something goes wrong, look deep into yourself—not in an emotional way, to blame yourself or indulge your feeling of guilt, but to make sure that you start your next campaign with a firmer step and greater vision.” Moving forward I’ve learned a lot from mentors and colleagues throughout my career, but I also enjoy looking for inspiration outside of my normal work environment. Greene’s book “The 33 Strategies of War” provides great inspiration in the form of quotes, advice, and stories from history for approaching life strategically and rationally. Greene’s book is also very grounded and realistic in its approach, and he encourages us to do the same: “While others may find beauty in endless dreams, warriors find it in reality, in awareness of limits, in making the most of what they have.” Whether we are focused on our own research projects, maneuvering into the world in search of fulfilling work, or just going through our day-to-day lives outside of work, we will encounter different types of battles. Greene’s book focuses on the importance of goals in waging this war, whether they are personal or professional: “Do not think about either your solid goals or your wishful dreams, and do not plan out your strategy on paper. Instead, think deeply about what you have—the tools and materials you will be working with. Ground yourself not in dreams and plans but in reality: think of your own skills or advantages.” “Think of it as finding your level—a perfect balance between what you are capable of and the task at hand. When the job you are doing is neither above nor below your talents but at your level, you are neither exhausted nor bored and depressed.” How we approach them depends on our own strategy, but we can all face them with courage and strength by adopting a warrior’s approach to facing conflict. Greene’s discussion about internal warfare might be one of the books’ most relevant sections for graduate students. There are numerous quotes in this book and it’s difficult to highlight all of the great advice discussed in just one blog post, but to close off the post, here is a post on the importance of having a warrior’s heart: “It is not numbers or strength that bring victory in war but whichever army goes into battle stronger in soul, their enemies generally cannot withstand them.”

I tend to get in trouble by our lab safety officer once every two weeks for not wearing a lab coat. I always wear one when working with some dangerous or caustic chemicals, but most of my time spent in a molecular biology lab isn’t hazardous to my health. The main reason that I don’t like to wear a lab coat when it’s not necessary is maybe an unusual one: I don’t want to look like a scientist. Even as a researcher who’s been working in a lab for the past 8 years, I don’t want to fit the stereotype of what a scientist looks like or acts like. But what is the stereotype of a scientist? How do they look and, most importantly, how do they act?

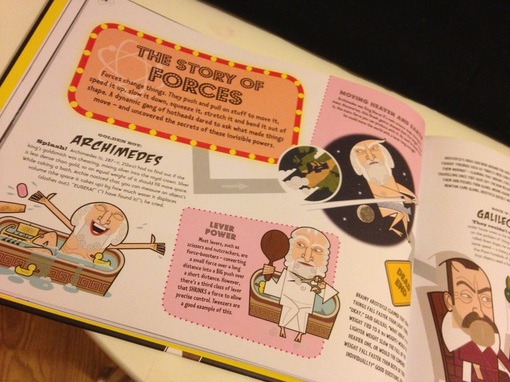

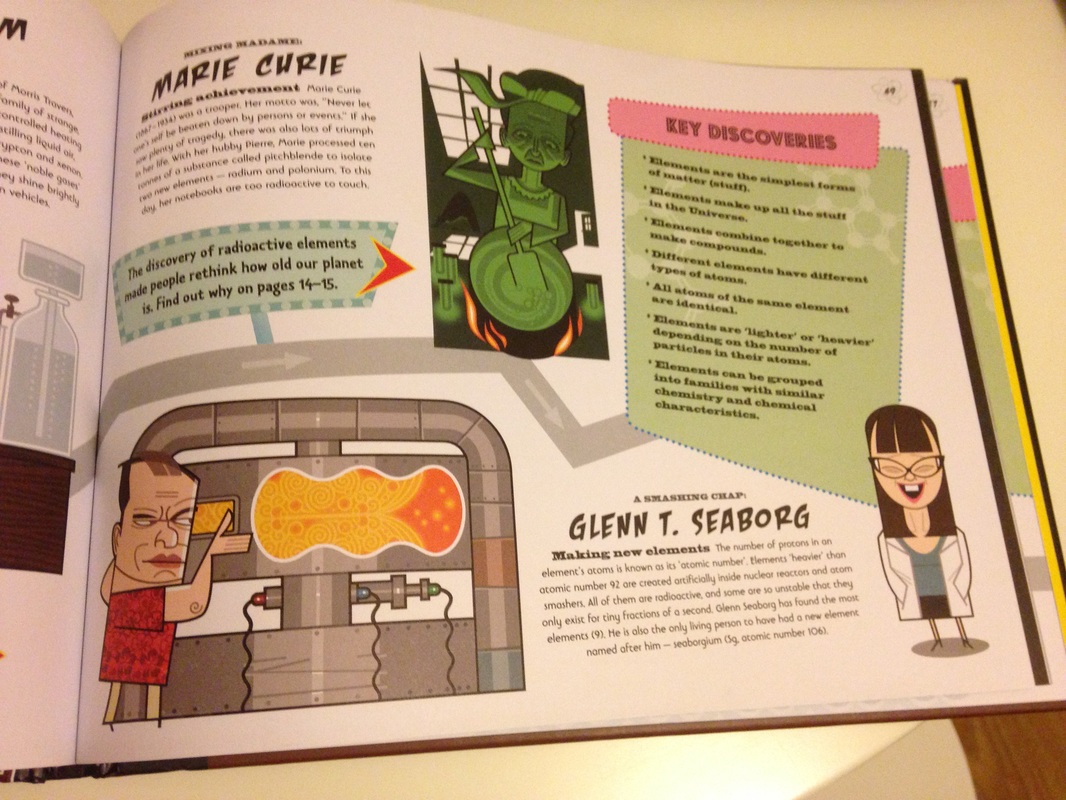

During this summer of lab work, writing, and tweeting, I’ve also been thinking about the ‘big gap’ in science, the gap between what the public thinks of what we do versus our actual research. PhD comics author Jorge Cham does a great job talking about this gap in his TEDxUCLA talk. Cham gives an example of good science communication in a collaborative project to develop a cartoon and video about the Higgs Boson. He makes note that this approach to sharing science took a lot of initiative from the scientists themselves, and it didn’t follow the traditional way of how science is shared with the broader community. Cham also comments on how shows like Big Bang theory portray researchers as eccentric and socially inept, which paints an inaccurate picture of scientists and can make the job seem unattractive to young students who don’t consider themselves geniuses or ‘nerds.’ While I do enjoy Sheldon’s banter on Big Bang Theory (because we all know someone like Sheldon in our group of colleagues or friends), I wonder if there’s a better way to talk about who scientists are and what they do. These wonderings led me to buy the children’s book, Rebel scientists, last week from Amazon. Rebels play a prominent role in modern-day storytelling: whether it’s Star Wars, Hunger Games, Braveheart, the Matrix, or the French and American revolutions, we all love to cheer for the rebels and the underdogs, be they real or fictional. But can scientists really be a part of this adjective? Dan Green’s book was one of the winners of the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize for this year. The illustrations, done by David Lyttleton, are a real treat for the eyes and help to focus the storytelling on the scientists themselves and how their work fits into the picture of our understanding of the universe. The book starts off with the timely question of “What is this thing called science?” and Dan describes it in four parts: curiosity, disagreement, discovery, and a long journey. Scientists are the ones who are curious about how the world around them works. They go against the consensus and the status quo when need be. They know that the world has a lot of mysteries that lie ahead and are driven by asking the why and how of everything and anything. Each science subject is presented as a separate chapter called “The story of ____”, with topics including the solar system, the atom, light, the elements, and genetics. Within each story, Dan starts with the early earliest thinkers and their ideas about how the world works, following through to what we know and are working on in science today. The book depicts the scientific exploration using a diagram of a road which connects discoveries together, while also provides road signs that the reader can follow to link to relevant material in other fields. The road even has the occasional dead end at an explanation of an idea that didn’t quite pan out. While the book is meant for a slightly older reader, probably for students ages 10-14, I’m amazed with the breadth of topics that are covered-and even complex subjects like quantum physics that I even had to re-read a couple of times to get the gist of the story. Below you can find a couple photos from inside the pages so you can get a sense of how the story of science and scientists are told by Dan:

I like how the book describes the Galileo’s and Einstein’s of our world: instead of calling them all geniuses or describing them as hyper-intelligent, the famous thinkers of our world are described with a wider breadth of words. ‘Rock star’, ‘radical’, rabble-rousers’, ‘sharp suited’, and ‘mavericks’ are just a few of the adjectives used. There are stories of disagreements between the biggest minds in science and how they came to a consensus about how the world works. There are stories of researchers going against the grain to pursue their ideas and delve into the mysteries that the rest of the world wasn’t able to see. At the end of the book, you can feel like the moniker of a ‘rebel scientist’ isn’t that far from the truth.

Reading this book also got me thinking about the other things that scientists do and that they are that might not come up at first though, since the thought of a 'rebel scientist' also wasn't the first to spring to mind. So what, exactly, do scientists do? We get things wrong, and that’s OK. There was more than one road in the Rebel Scientists book that lead to a dead end. But it wasn’t mentioned as a bad thing or that the person who thought the idea was stupid, it’s just a part of the process of science. Modern day science is rife with failures, experiments that go wrong, and ideas that lead to dead ends. It doesn’t mean we’re doing our job wrong, but it may not come to mind to non-scientists that as scientists we might not actually know everything. As Jorge Cham said in his talk, 95% of what makes up the universe is unknown…our world is complex and we have a lot more work to do! We are diverse, but we can do better going forward. A majority of scientists that feature prominently in history are men from Europe and North America. Some women do make an appearance, as well as a few Arabian scientists, but historically the science community hasn’t been diverse. The modern landscape is more inclusive, but we can still do better. What steps can we take in the future to ensure that everyone has the chance to contribute to the scientific community? Our job is to challenge the status quo. While scientists might be interpreted as know-it-alls or geniuses who can memorize textbooks and equations, a scientist cannot succeed simply by rout memorization of existing knowledge. Scientists have to be rebels that go against the grain, because that’s how we learn, uncover, and discover. To succeed in science, you have to do the unexpected, and being an elite know-it-all will only hold you back from uncovering the secrets that the universe has hidden from plain view. As Einstein said (and you can read more about him on Page 72 of Rebel Scientists), “Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” We do our best when we work as a team and not against each other. There are a lot of dramatic rivals highlighted in Rebel Scientists, and those of us that work in a lab will know of a few other ‘rivals’ of our advisors, collaborators, and colleagues. But what I like about this book is how it highlights the ideas that were put forth not by competing groups but by scientists working together to put the pieces of a puzzle into a single, clear picture. It’s tempting to want to blaze our own trail to fame and glory, so this book is a nice reminder that if the goal is the search for truth and understanding about the universe, working alongside others is better than working in opposition. Our world is an exciting, terrifying, and unimaginably big place. Figuring out how and why it works the way it does takes brave, enthusiastic, and rebellious minds. If people can rally behind the rebels of the science world as they do for Luke Skywalker or Katniss Everdeen, then Rebel Science will have succeeded in its mission. I hope to see more authors like Dan Green who are working to change the story of science and scientists into something more accurate and more engaging. May the force be with us and the odds ever in our favor!  You can pick up the book on Amazon or at www.bornforthisbook.com You can pick up the book on Amazon or at www.bornforthisbook.com

Some days at work I catch myself thinking “I didn’t sign up for this!”, whether it’s while thumbing through pages of statistical test reports or signing up to use the electron microscope for the third Friday afternoon in a row. The ways in which we spend our working hours can leave us feeling like we’re in the wrong place, like this is not the work we were put here on earth to do. Keeping with the pace so far of this summer of book reviews, I couldn’t resist a quick read of Chris Guillebeau’s Born For This, a book that’s out there to tell us all that we are, indeed, born for something greater than endless days of feeling we’re stuck doing the wrong sort of job.

I first heard of Chris’ book while perusing Gretchen Rubin’s website and was hooked on the concept of finding the work you were ‘born’ to do after taking the online quiz which accompanies the Born for This book. According to the quiz, I’m a dynamic organizer, and the description seemed to fit me to a T: a person who feels comfortable with structure but who craves flexibility, who likes to keep busy but hates feeling stressed, and a person who has seemingly opposite desires to both work independently and to be collaborative. The quiz was quick and easy but the detailed description also felt really accurate, which prompted me to check out Born for This at the library to see exactly what else it had to say. Reading the book was especially timely since I am approaching a pivotal transition point in my career: my current post-doc contract will finish this spring and I am looking around for where to go next. Even if you don’t find yourself in a similar situation, this book is a great read regardless of what career stage you’re at. I would actually encourage those of you early in their scientific careers, who are getting ready to get into the nitty gritty of the next stage of life as a scientist, to use the tips in this book as a way to get a leg-up on your future career. But regardless of what stage you’re at, there are a lot of great talking points in this book, and you don’t have to be an independent business owner or an entrepreneur to use them. At first glance it may seem like the book is only intended for those who are looking for a major career transition or are looking to start their own money-making scheme at home, but the book has a wider relevance than that. Being more entrepreneurially-minded is especially important in this day and age of scientific research, when networking and promoting yourself is another part of your job description. In this sense, acting like an entrepreneur by gaining some insights from people who have succeeded outside the lab can really help set you up for success as you move further and further into your dream job territory. The first few chapters of Born for This are focused on helping you discover the work you were meant to do, followed by tips and tricks of how you can go about getting that job. While most laboratory-based scientists may find it hard to be self-employed (the start-up capital required for your own HPLC or genome sequencer will likely hold you back), the lessons in the first part of this book can help you figure out what you’re good at, what drives you, and how you can make money doing it. Throughout the book, Chris also gives several examples and stories of people he’s met over the years who have been successful either at transitioning into a new career, breaking into a difficult to get into field, or setting off on a new and eventually successful business venture. These stories are inspiring in their own right, as well as Chris’ own story of jumping around from job to job and country to country before finding his own voice in helping people in their own careers, and serve to motivate and encourage readers as they venture through their own bit of career soul-searching. If you look at the stories presented in Born for This, you can see a common thread that connects all of these successful people together: each of them identified a goal and pursued it wholeheartedly, or they identified a set of guiding values and followed them clearly. Regardless of which way you go, the first step is same: What do you value and what is it that you want to achieve? When I ask people why they got started in graduate school, the theme of loving research is always there, and while we all enjoy the pursuit of knowledge, it’s also a very vague answer. What exactly is it about science and research that drives us to finish the mundane tasks? Is it the dream or hope that our work will make an impact on the world? Is it learning something new every day? Is it the opportunity to teach or give back to the community? Is it the fact that we get to play with flammable chemicals or liquid nitrogen and that working in a lab feels ‘cool’? Whatever your answer may be, simply ‘doing research’ isn’t enough of a detailed answer to lead us to the next stage of figuring out what we were born to do. To figure out what this job exactly is, Chris provides a model and a quiz exercise in Born for This as a way to think about what a fulfilling career has. Chris calls this the joy-money-flow model: a job should be something that makes us happy, provide enough money to live, and should maximize your own unique skillset. An ideal job is one that maximizes all three in that it’s what you like to do (joy), it supports you (money), and is something you’re good at (flow). The quiz exercise found in the book is a helpful guide for working through what parts of the model your current job is or isn’t meeting, and what types of work are ideal for your needs. For example, many young scientists love ‘doing research’, but may find that aspects of academic research such as writing grant proposals or working with undergraduate students don’t fit in with the joy or the flow part of the model. Thinking about how your work can maximize each aspect of the model can help you get into more specifics, and also brings in your own expertise and skillset into the equation. As another example, you may enjoy doing research but find that one of your skills includes working with K-12 students or in working with business clients. In this scenario, even though you enjoy research, you may be able to find additional career satisfaction in another field such as working at a science museum or becoming an industry consultant. Another great piece of advice that Chris offers in terms of figuring out your flow is by thinking of how others ask you for help. What is your role in a group setting or in the lab as a whole? What do colleagues ask you for your help or opinion on? If you’re not in a position where you feel like you get asked for help, you can try the opposite by reaching out to your work colleagues and asking them what they need help with. And if you have ideas of what you’re good at already in mind, you can try reaching out to contacts and colleagues you’ve already made and offer them help with a specific task that you think they would appreciate. Maybe you’re really good at making schematics for presentations, and you know your lab mate is giving a talk on some new data at an upcoming conference. Offer to make a slide for them in your spare time and who knows-it could lead to your own science graphics side hustle! One concept from early on in the book that I though was particularly relevant for scientists is this: even if you get a paycheck on a regular basis and have an employer, an office, and a seemingly ‘9-5’ type of job, we are all at some level self-employed. If you want to go beyond where you’re at now in your work, there’s no one else in your company or university can make your career happen except for you. We spend our time in graduate school being mentored and as recent graduates learning more skills, but at the end of a contract it’s our responsibility to make our own career. Even in more stable settings like industry, where you don’t have to deal with the pressure of short-term contracts and grant proposals, good people can still end up losing good jobs, which highlights the importance of putting your own career in your own hands as much as possible. I have a good friend in Omaha who worked for a Fortune 500 company which decided, after nearly 25 years of being in the same location, to move to Chicago and subsequently started laying off staff around Christmas. She was lucky to have kept her job, but others who had been working at the company loyally for years weren’t so lucky. Being responsible for your own career and fostering your own professional network won’t guarantee you a job if things go wrong, but by investing in yourself and giving time to someone besides the company that pays your bills can pay off in the event that things take a turn for the worse. Remember that even when you change jobs or have to move to another part of your career, you get to take your personal network and professional connections and your reputation with you, so be sure to give them the care and attention they need to help you succeed! Outside of the entrepreneurial/self-employment perspective, Chris also gives some sound advice for the job search. As detailed in this book, the job search is a game of imperfect information and multiple strategies (think of poker versus chess: poker has imperfect information while chess has perfect information, since you can see the full game board). Chris recommends a winning strategy that includes 1) having a back-up plan for any major decision, 2) taking out a ‘career insurance policy’ by having good relations within your professional network, 3) asking five people to help you while starting your career search (on things like finding leads for a job, an introduction to another colleague, or a skype chat to talk about the layout of your CV), and 4) creating an ‘artist’s statement’ which describes your work, your goals, and who you are. Chris states that in the service industry, a good reputation is an asset-and that’s certainly the case in science as well. Foster your professional network even in the times when they aren’t directly needed, and be useful and helpful to the people you know so you’ll be remembered as an engaging and hard-working person. I’ll avoid re-telling Chris’ entire book here, but will leave you with this reminder from Born for This: It’s OK to feel like you’re learning more about what you don’t want to do in the early stages of your career. In the long run, knowing what you don’t like can help guide you to an ideal career as much as the positive experiences. Part of getting to that perfect career is to go through a range of experiences, from incredible and rewarding moments to the frustrating days where all you wanted to do was to have 5pm roll around. You won’t know what your ideal job is right away, and that’s normal. Reading through the numerous stories of people in soul-searching mode reminded me of that, and it shows that finding the work you were born to do is very rarely a simple or linear journey. Science will always be a challenging field to work in, but it is also a place where active and enterprising young scientists, ones who are adaptive to new ways of thinking, communicating, and planning, are poised to leap ahead. I greatly enjoyed reading Born for This, and have only given a small taste of what he lays out in his book. Even if you’re not planning a major career shift, the strategies in Born for This in terms of building up your professional network and ‘fanbase’ are great life lessons for the early stage of a career, whether you’re an archaeologist, a zoologist, or anything else in between. Chris’ book is also a great reminder that there is no one size fits all career, and that part of the joy in finding what we were born to do is in recognizing what we’re good at and what we’re passionate about. Finding a way to get paid for what drives and inspires us is an added bonus!  Image courtesy of Island Press Image courtesy of Island Press

We’ve talked in previous posts about many of the additional jobs required of scientists besides research. Science communication is at the top of the list, and the importance of strong communication skills for scientists has become clearer now than ever before. In some of our previous posts, we’ve focused on ways you can communicate your science when asked the dreaded question of ‘So, how’s research?’ at a get-together with family or friends or how you can adopt the use of a narrative approach to set up your scientific story. It’s also important for us to think beyond our own research and consider sharing the concepts, findings, and ideas of an entire field of study. Are there ways that we can better communicate the wider scope of our scientific research to an even broader audience?

At the SETAC meeting last autumn in Salt Lake City, I had a chance to catch up with my undergrad thesis advisor Dr. Alan Kolok, who set out to do just that for toxicology. I spoke with him over the phone this winter about his project of writing Modern Poisons and his perspectives on undertaking the endeavor of translating toxicology for a lay audience. I also had a chance to read the newly-minted e-book version this spring, which you can pick up on Amazon or directly from the Island Press website. You might find the book a surprisingly short read, something you can get through in a week or so of easy reading, and there’s a reason for that. Kolok was initially inspired by the paperback Why big fierce animals are rare, a book written by the late Paul Colinvaix, an ecology professor who worked at The Ohio State University and later at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. The book is dense in basic ecology but uses short, 5-minute chapters to get the message across. Kolok was inspired by the book as an undergraduate student and the way in which these complex concepts in ecology could be conveyed in short, easy-to-read sections for a broad audience. Kolok wanted to do something similar for the field of toxicology: a book that could be read by anyone, from accountant to zoologist, and a book that would enable them to have a better understanding of the concepts and common misconceptions within toxicology. As researchers we work primarily in a single field and with the occasional jaunt into interdisciplinary territory. It’s easy to forget how specialized we are even compared to scientists working in other fields, even ones that might seem similar at first. Kolok was initially surprised by comments on a grant proposal to the National Science Foundation about why PCBS aren’t metabolized but PAHs are and why EDCs impact fish differently than humans. To the toxicologist, these concepts (and acronyms) seem like common knowledge, but for someone who’s an epidemiologist or an electrophysiologist won’t understand concepts like biotransformation as much as a toxicologist will. After seeing these comments, Kolok realized that even for a field as large as toxicology, there was really only one major textbook dedicated to the principles of the field. While this is a great textbook, it’s not exactly pocket-sized, and certainly not a light read or for those who simply want to pique their interest on the topic. Three years ago, Kolok set out to write Modern Poisons as a short and easy-to-digest book on the basics of toxicology. While the book is currently available as an undergraduate textbook, it was initially meant to be a short book for lay readers, including advanced high school students, who are interested in toxicology. In order to reach this broad audience, Kolok’s approach was to use the power of metaphors. Kolok is a firm believer of the value of anecdotes as a way of explaining complex concepts to people who don’t come from a scientific background. This approach is used to tackle topics ranging from the geographical distribution of pollutants to emerging questions on topics including nanomaterials and personal care products. This approach enables readers to understand the gist of the problem but leaves the in-depth details for another story. What became more of a struggle for Kolok during the writing process was achieving the balance between sufficient complexity with understandability. In the past 17 years of teaching toxicology for senior undergraduates at UNO, Kolok has found that a good portion of the course ended up being the study of biochemical pathways. While this isn’t the core of toxicology per se, it was still something that all students needed to understand so that concepts such as enzyme induction by dioxins and pesticides binding to the acetylcholine receptor could be better understood. The book subsequently follows in parallel to how Kolok teaches, not only in the specifics of the enzymes and pathways discussed but in general in the sense of how the system works as a whole and how different pieces can end up in disarray during a chemical onslaught. Kolok used Modern Poisons as a textbook in his toxicology course last autumn, where he provided the book as an overview and then used the course to go into greater details. While this required Kolok to re-think his course and revamp his presentation style, he was also able to get feedback on the book before it went to publication. His students really enjoyed the book and were able to read each chapter and make specific comments on what worked and what didn’t. After four years of droll textbooks for classes, Kolok’s senior-level toxicology course enjoyed a book with a more conversational and informal tone and approach, and Kolok plans to use Modern Poisons again in the upcoming semester. While the book did take three years to write, it wasn’t evenly spread over all 20 chapters. Kolok found that some ideas or concepts came easier and were written faster, while for others he needed to either think about how to go into detail while still being clear, and other concepts required him to go back to the literature. The amount of time spent during that year also varied, as Kolok was still teaching and doing research, but on some occasions spent nearly 20 hours a week at writing. Thanks to a quarterly series of articles he had written for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Kolok did have some starting material from 16 lay person articles of around 800 words, each focused on a topic within toxicology. Even with some starting material, however, the process was still not always an easy one. “When you’re writing a review paper, your input is scientific material and your output is more scientific material. It’s harder when you’re taking scientific materials and translating them into something else. You have to read a lot in order to understand and then translate without losing the complexity,” Kolok commented. Kolok admitted that he wasn’t always the most efficient at this: some concepts ended up ‘translating’ rather easily but others were more difficult, and some ideas and chapters had to be completely redone. Kolok reinforced the need for good self-critique during the writing process and admitting when you need to restart something completely. While this was a challenge throughout the writing process, Kolok admits that “When you feel like you finally got it right, it’s really satisfying.” While the first edition of the book is done and in print (or e-book, if you prefer a digital format), Kolok is already thinking about what the next version will look like, but after some time off from book writing, since Kolok emphasized that part of being productive also involves taking a break now and again. The next edition is likely to include some figures and a few changes in sections that Kolok feel could be improved, especially as new research comes out and new stories become prominent in the news, and to go into more detail on certain topics that could only be covered broadly in the first iteration. “I’d never thought of myself as a writer until finishing this book,” Kolok remarked, and said that by writing this book he activated a more creative part of his brain than normal science writing. “This type of writing feels like a creative challenge compared to scientific writing. I got to expand my creativity and the horizon of my writing, I got to use more creative words and tell short stories instead of journal articles.” Kolok even went so far as to say that writing more creatively felt like learning a new lab technique, and that while in research and as a professor he was and is still writing, he now has a new perspective on it. Kolok even said that the amount of scientific writing he’s done has increased, and he’s now more motivated to write and finish papers, in addition to thinking about continuing his career in writing after retiring from research as a second career. I greatly enjoyed reading Modern Poisons, and even having background knowledge in toxicology the book didn’t feel like anything was too glossed over or watered down. One student commented that “Dr. K writes like he talks, very conversationally, and I mean that in a good way,” and I certainly agree with that sentiment. Reading this book felt like being in Kolok’s undergraduate toxicology course all over again, a reminder of why I began my PhD in toxicology in the first place: the fascination I felt while learning about what happens when good biological plans and infrastructure go awry. It also spurred my own thoughts on how I could talk about my own research better, which was one of the topics not mentioned in Kolok’s book: narcosis. I agree with Kolok that toxicology should be understood by more than toxicologists, especially since a lot of what we do impacts what chemicals we use in our homes, on our foods, and in our drugs. I’ve already passed along the book to science-oriented friends and non-science-oriented family members who have asked me time and time again to tell them about what I’m doing at work. Thanks to Dr. K, I can just send them the link to the Amazon page and avoid a lengthy discussion on biological membranes over Christmas dinner! It’s not just toxicology that benefits from books like this: scientists are trained to become specialized in their own fields, and a person that hasn’t been in a science class since high school may have forgotten what the inside of a cell looks like or from what direction the moon rises from. While it may not be an easy endeavor to bring every research concept to the lay person, now is the time to start thinking how you can translate science into a story that people can connect and relate to. I’m thankful for Dr. Kolok’s inspiration in telling the story of toxicology for everyone, and am hopeful that more science-oriented books like this in the future will grace the bedside tables of many curious readers to come.

Carl Sagan is a hero of science communication: his books and TV series provided a forum for people to learn about science, and he sought to make nebulous topics understandable and interesting for everyone, not just for scientists. Science Friday recently posted an interview in honor of his birthday, which inspired me to explore one of his non-fiction pieces which he mentioned in the interview in greater detail. I am a huge fan of his book ‘Contact’, which I devoured two years ago and consider it one of my science fiction favorites. Over the past couple of weeks I’ve been reading his book published in 1995, ‘The Demon-Haunted World,’ with the running subtitle ’Science as a candle in a dark world.’ To provide some perspectives on the topics he addressed in this book while still giving you motivation to actually read it yourself, I’ll highlight some of his points that stuck the most with me and connect them to what I see as the current struggles between science and society.

Science should be a cautious mix of skepticism and wonder Sagan mentions his parents as a source of inspiration for his own career in science. Not because they themselves were scientists, but because they helped instill in him both a sense of wonder about the world and the complementary skepticism needed to distinguish the true from the untrue. Sagan comes back to these two qualities quite often in his book and relates them as the crucial factor for being a good scientist. You must have a passion to learn about the universe, the wonder and the inspiration that keeps you going through mundane scientific tasks or during the times when it feels like nothing is working. At the same time, you need the skepticism to keep your hypotheses in check, to be able to look at results with a sharp and critical eye, and to prevent yourself from becoming too dreamy-eyed about an idea when new evidence shows up against it. This sense of wonder seems to come naturally to many of us, especially as kids when they start learning about the world, and this natural wonder is the reason why many of us got involved with science in the first place. Being excited to learn about the universe we all inhabit is the driving force behind many endeavors—but it’s the skepticism and the thorough approach that distinguishes science from purely creative endeavors. Scientists and engineers must balance a seemingly contrasting set of ideals and methods: we must be imaginative enough to bring new ideas and perspectives together, but at the same time disciplined enough to know when the logic of an argument doesn’t hold up. The methods of science are more important that the answers Science is very different from other fields because its passion and its core lie in framing testable questions and conducting definitive experiments. While this problem-solving nature is instinctive to the human condition, we still have to be careful in terms of how we set about asking questions and what we do when we get back the answers. A fundamental theme that Sagan stresses is that scientific theories can and should shift when new results reveal a new understanding. This can give some people the impression that scientists are constantly changing their minds and therefore aren’t trustworthy. This can be addressed by better explaining the concept of the scientific method and how theories come and go as new knowledge arises. At the same time, scientists can have a habit of getting overly attached to a hypothesis or an idea, especially if it’s something that they’ve received grant money for pursuing further. Sagan stresses just how important it is for a scientist to be willing to change their ideas when support in the form of data becomes available. As such, scientists should always be striving for new ideas and, regardless of whether their initial ideas were right or not, should aim to leave behind a legacy that can be built upon and amended as needed. Skepticism as a key tenant of science and of life Sagan’s perspectives as an astronomer led him to many interesting encounters with UFO abductees and astrologists. Regardless of what field you’re in, there is probably some related form of pseudoscience that develops from people’s general fears, misinterpretation of science, and a resistance to asking testable questions. Sagan believed that skepticism provided the best way to dispel the haunting demons of pseudoscience. His idea was to provide better training to help students develop their own skills in skepticism, or as he terms it their ‘baloney detection kit.’ Sagan describes his kit in great detail and again brings it back to the scientific method: you start with the results presented to you, whether they be raw data or observations, then try to explain what you see with a testable hypothesis (the key here being testable). Sagan suggested that this skepticism could be instilled in earlier years by having academic scientists more involved in public education settings, and to make it clearer that science is not just about results but also the questions and experiments you use to get there. A look at the ‘demon-haunted world’ 20 years later In today’s world, science is at the forefront of daily news websites, and journal articles are published more quickly and made available more widely than ever before. Newspapers have science columns and science journalists, and there is a reason for that: science can bring in some juicy, dramatic stories. Between predictions about global warming, new cures for cancers, and water on Mars, there are a lot of attention-worthy stories in science today. It’s for this reason that good science and accurately talking about the scientific method, as well as the implications of findings, is so important. Ideas like ‘vaccines cause autism’ are hard to erase from the public mind, even after a paper gets retracted, so having both scientists and lay people being at the forefront of solid science and accurate interpretations of studies is crucial. In my own line of work as an environmental toxicologist, I see demons coming to life not in the form of UFOs and star signs but in the obsession with ‘chemicals.’ There is certainly no doubt that the industrial has severely impacted our environment: pesticides that kill more than just bugs, rivers that catch on fire due to toxic waste, and oil spills that last for 87 days. Because of these very impactful stories, discussions on the use of chemicals and where they end up in the environment can quickly become polarized, especially if they involve impacts on human health. While these dialogues are crucial, the issues can often become overly simplified as a battle between the bad industry company and the good little guy who is unjustly exposed to these evil chemicals. There are plenty of examples of sensationalism and misinterpretation of science in the area of health, with other science bloggers keen to bring to light logical errors on 'poisoning' exposés, which included statements such as ‘there is just no acceptable level of any chemical to ingest, ever’ (not even water, apparently!). In these heated discussions, it becomes quite easy to craft a story of injustice and to point fingers at the big corporations that are ‘poisoning’ us or our environments with chemicals and then to say that we’re being stepped on. In reality, these problems often have a myriad of stakeholders and there’s no bad guy versus good guy, its just different groups with different needs and perspectives. While there will likely continue to be misinterpretations and over simplification of the issues plaguing our world, the goal of science in these debates is to help clarify the ever-present gray area and act as the mediator in these discussions. Sagan strives in his writings and TV shows to help everyone learn about science and how it works, because our success in the future is dependent on science, mathematics, and technology. However, with as much pressure that rests on these fields to deliver solutions, these topics remain poorly understood by many of the people that they impact. As scientists, we have numerous skills that go beyond pipetting: we are good at thinking, working in teams, solving problems, communicating, and teaching. We can put these skills to good use not only to advance scientific progress but also to share science with society. In this book, Sagan not only provides a guide for lay people to understand science but also provides inspiration for scientists to continue his saga of science outreach. Through positive collaborations and more engaging and open forms of communication, we can work towards Sagan’s vision of using science to keep the world’s demons at bay, and to usher in a society that has the same passion for understanding the natural world as the scientists who work towards that goal every single day. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed