Facing the challenges of a career in STEM

Portions of this post were originally shared as part of a SETAC women’s workshop fundraiser On the night before I started my post-doc, my mother sent me an email with her best career advice. It was my first job after graduate school, and her message was a way to wish me well and to help me start with my best foot forward. Her advice included Be present; Find meaning and happiness in what you do; Don’t sell yourself short; and Don’t look for others to validate what you’re doing. During those first few months, I remembered her advice and did my best to embrace it. I faced challenges and issues in my post-doc, as expected in any new job , but overall I felt confident in what I was doing. I felt like I was placing myself in the right career trajectory. But a year and a half later into my post-doc, another piece of advice rang loudly in my ears. It wasn’t because I had followed my mom’s advice but rather because I had gone against it. I went home after having a complete crying break-down in my boss’s office, feeling horrible for not having followed my mother’s simple advice: Don’t cry at work. As much as I tried to move on from what was a quintessentially bad day, I felt myself becoming increasingly distressed and anxious about my job and my career. I felt guilty about my break-down and worried that I would be seen as weak and overly emotional. I felt like I had gone from being an up-and-coming independent scientist to the girl who cried in the office. More than anything, I struggled with the feeling that I was no longer on the right career path. I wondered if I was not ‘cut out’ for life as a scientist or as a researcher. Unique challenges for Women in STEM: Self-confidence in times of stress I was fortunate that the stress that had taken over my day-to-day life eventually resolved itself. The months I had spent dealing with new and urgent tasks and the endless shifts in my project’s aims finally came to a resolution and I had a clear path ahead for what needed to be finished by the end of my post-doc. The fear of not having my contract extended was alleviated when the paperwork came through and I was relieved to find that my job would not end as abruptly as anticipated. But I still struggled with feeling like I was not a good scientist. If I had gotten to the point where I cried at lab, was I really cut out for life as a researcher? It was at this point that I had to force myself to realize that I was not a bad scientist just because I had become frustrated. I was organized, hard-working, and forward-thinking. The thing I was lacking was the self-confidence. Confidence is the resounding voice in your head that tells you “I can do this”—and when you hear that voice, you believe it. Confidence lets you see your positive attributes at difficult times, and also helps you recognize that the mistakes you make on one stressful afternoon don’t have to define you in the long term. We touched on this topic in a post earlier this year and discussed the importance of self-confidence for navigating through the numerous challenges you might face as an early career researcher. A lack of self-confidence is not a unique challenge that early career researchers face, and I am certainly not the first person to wonder whether I was ‘cut out’ for something or not. In particular, women who embark on careers in science face unique challenges related to self-confidence, even from a young age. When children are told a story of a person who is described as “really, really smart” and are then asked to select a gender for the person in the story, girls as young as 6 years old were more likely to identify that “really, really smart” person as a man. Girls were also less likely to play games that described as being for “children who are really, really smart”. Another study found that 10th grade girls tended to rank themselves as less skilled in math and science than their male counterparts, even if the girls’ test scores reflected strong abilities in STEM. Even though it was the girls who performed better on tests, it was the boys who saw themselves as being more skilled in math and science. How can we build better self-confidence for women in STEM? Our own internal dialogue is a powerful force that dictates our actions and reactions. When we don’t know how to counter our own negative impressions of our abilities or have low self-confidence in general, it can make pursuing a career in STEM challenging. A lack of confidence makes science seem like it’s only meant for the “really, really smart” people. Given the importance of self-confidence in pursuing and staying within a career in science, how can we better encourage women in STEM to stay the course and work through the more challenging times as they come? One recent study provides an example of the importance of peer mentorship as sources of inspiration for motivating women. The researchers looked at exercise habits and found that people are inspired to run faster and train harder when they see friends sharing their own fitness stories on social media. But the most noteworthy finding from this research was that while men can find inspiration from both male and female friends, women tend to only become inspired to exercise harder when they see stories from other women. If we want to encourage more women to become scientists, we as women scientists can start by encouraging self-confidence and serve as mentors for girls who are looking for someone to inspire and support them. Another recent study demonstrated how female engineering undergraduate students were more likely to feel more confident in their technical abilities, as well as their perception of their ability to overcome stress or challenges, when they were connected with a female mentor at the start of their program. Female undergraduate students who had no mentors, on the other hand, were more likely to feel out of place and anxious, with 11% dropping out of the program entirely (in contrast, all of the female students who had female mentors remained in the program). Interestingly enough, grades had no bearing on whether a student remained in the program or not—but the presence of a mentor did. What does the future hold? It can seem daunting to look at the facts and figures related to women in STEM and contemplate a way forward. But by recognizing the fundamental importance that self-confidence and mentorship can impart on young minds, we can bring all of the best and brightest minds to science—and make it clear to them that they are welcome, and able, to stay. If you are working in STEM and are struggling to find your place in the community, start by working independently towards improving your own self-confidence. While you work on building yourself up internally, start your search for your networking support team by reading our Research Entourage series. These articles focus on the characteristics of the members of your career development team, the people who can work with you and support you as you move forward in your career. If you are lucky enough to feel confident in your career path and want to help the next generation of scientists and engineers, you can volunteer to serve as a mentor for girls and women in STEM. You can also explore the outreach activities happening at your institute and get involved with local events happening in your community that are STEM focused. One great example in the UK is Soapbox Science, an organization that recruits and supports women scientists for science communication and public engagement activities. Becoming a confident scientist The life of a scientist will always be fraught with challenges as well as rewards, joys, and ‘eureka!’ moments. After my stressful moments in the lab, I realized that my frustration and tears were not a sign of weakness but were instead a realization that the job I was in was not the right fit for me. With this realization, I was able to focus my energy on finding a new STEM career path that was a better fit for both my expertise and my passions. I’m now enjoying my third month as a medical writer, a job that feels like the right area of STEM for me. My hope is that by finding your own self-confidence and bringing together your research entourage, you can find the job that's the right fit for you!

The strategic graduate student

An early career researcher faces a lot of pressures within the academic research environment. We’re expected to work hard and put in long hours on experiments and data analysis, under the idea that more output (or, in our case, more data) will inevitably lead to more papers and more opportunities. Hard work is a crucial aspect of success in graduate school, but what’s sometimes not as clear, especially in the early periods of our research careers, is how to work smart. Working smart means being strategic with time: set goals, plan ahead, and adapt as needed. But how exactly can we learn to become more strategic in our work? It’s one thing to design a flawless plan of experiments and analyses in great detail…but what about when an unexpected results offers new insights or inspires different experiments? With an endless array of tasks, distractions, and the all-enveloping feeling like we have to be doing something at any given point in time, how can we clearly see and decide on the most valuable course of action at any given moment? I’ve been interested in answering this question both in a broad sense as well as for my own work-life balance. And while I’ve had wonderful mentors, coaches, and bosses who have taught me how to prioritize my current work while visualizing the future, I also like to find inspiration from other sources. My reading hobby typically leads me towards history books, in part as a break from reading about science but also as a source of awe-inspiring stories. It’s incredible how often the lives of the great men and women of history were defined by how they made pivotal strategic decisions or how a single idea changed the entire course of history. One of my recent such reads was Robert Greene’s “The 33 Strategies of War”. Greene’s book offers insights on how you can make your own career, or even your entire life, more strategic. The book is interwoven with stories from history highlighting the 33 concepts described in great detail in his book. If you’re not a military history aficionado, there are also a number of stories about politicians, business leaders, and even artists who fought in their own sort of ‘wars’ as they worked to bring their goals and ideas to life. Highlights from “The 33 Strategies of War” Greene’s book is not a practical ‘How to make war’ type of book. It instead focuses more on the psychology of conflict and how to approach these situations with a rational and strategic mind. One of the most important facets of good strategy is to have a wide perspective of your situation. In the case of research, you should thoroughly understand the problems that your field is working to solve and the possible solutions: “To have the power that only strategy can bring, you must be able to elevate yourself above the battlefield, to focus on your long-term objectives, to craft an entire campaign, to get out of the reactive mode that so many battles in life lock you into.” “The essence of strategy is not to carry out a brilliant plan that proceeds in steps: it is to put yourself in situations where you have more options than the enemy does. Instead of grasping at Option A as the single right answer, true strategy is positioning yourself to be able to do A, B, or C depending on the circumstances. This is strategic depth of thinking, as opposed to formulaic thinking.” Greene also stresses the importance of acting on the plans you make while being flexible to changing situations. While strategy is the “art of commanding the entire military operation”, tactics refers to the “skill of forming up the army for battle itself and dealing with the immediate needs of the battlefield.” You can think of strategy as the plans you draw up for the experiments you need complete for your dissertation and tactics as the action you take if you find out that one of those experiments was already done by another lab or is no longer needed because another paper refuted the hypothesis. And regardless of how well you plan, you must also be ready to work hard and to learn from any mistakes you make. As Greene said: “What you know must transfer into action, and action must translate into knowledge.” Greene’s book discusses how to use both victory and defeat to your advantage. Both victory and defeat are temporary, says Greene, because what matters is what you do with the lessons you gain from each encounter. If you win, don’t become blinded by your own success but keep working hard and moving forward. If you lose, envision your loss as a temporary setback and use the lessons learned to plant the seeds of future victory. Greene also talks extensively about the way that emotions can cause you to make ill-informed decisions. This is especially true for academics and young researchers, where the pressures to work hard and publish can lead many to mental health problems or simply finding themselves burned out from exhaustion. Many of the stories in 33 Strategies of War show how people extricated themselves from difficult situations and provide hope for the rest of us that anyone can make it through any type of challenge we might face: “Fear will make you overestimate the enemy and act too defensively. Anger and impatience will draw you into rash actions that will cut off your options.” To become a strategic student, start by waging a war against yourself Greene’s book goes into great detail on the many facets of war, including offensive and defensive tactics as well as methods for psychological warfare. What I found the most resonant, especially for early career researchers, were the discussions around internal warfare: ‘declaring war on yourself’ in order to progress and move forward. Greene also focuses on the importance of self-confidence and having a positive mindset—a topic we discussed earlier this spring. One of the most striking personal stories in this section is about General George S. Patton, the famous WWII general who was instrumental in leading the Allies to victory. But before he was a WWII general, he found himself commanding a small contingent of tanks in France during WWI. At one point his unit ended up trapped, their retreat back to base blocked and the only way forward through enemy lines. He found himself terrified to the point of being unable to move or speak. In the end he was able to muster enough courage and stride forward, but the moment left a mark on Patton. He made a habit of putting himself into dangerous situations more regularly, to face that which he feared in order to become less afraid of the situation. This is one of my favorite stories from 33 Strategies of War. It not only shows us the human side of a great general from modern history, but it also shows us the importance of facing our fears. There are many unknowns, uncertainties, and even fears we face in our own work: what if we get something wrong, what if an experiment fails, what if we don’t win that grant or fellowship. But putting ourselves into challenging situations is part of how we progress. Facing and embracing what we fear helps us move forward and lessens our anxiety surrounding failure. Another important consideration for graduate students and early career researchers is the importance of taking time away from our work. We’ve discussed the importance of breaks and time away from the lab to give us perspective on our work and refresh our minds, and Greene also highlights this as a strategic move: “If you are always advancing, always attacking, always responding to people emotionally, you have no time to gain perspectives.” Through these opening chapters, Greene explores this internal war and how we can develop a warrior’s heart and mindset. Instead of summarizing the chapter in great detail, I’ve highlighted are a few of my favorite quotes from this part of his book: “He (the warrior) must beat off these attacks he delivers against himself, and cast out the doubts born of failure. Forget them, and remember only the lessons to be learned from defeat—they are worth more than from victory” (About your presence of mind): “You must actively resist the emotional pull of the moment, staying decisive, confident, and aggressive no matter what hits you.” (On being mentally prepared for ‘war’): “When a crisis does come, your mind will already be calm and prepared. Once presence of mind becomes a habit, it will never abandon you.” and “The more you have lost your balance, the more you will know about how to right yourself.” (About keeping an open mind): “Clearing your head of everything you thought you knew, even your most cherished ideas, will give you the mental space to be educated by your present experience.” (About self-confidence): “Our greatest weakness is losing heart, doubting ourselves, becoming unnecessarily cautious. Being more careful is not what we need; that is just a screen for our fear of conflict and of making a mistake. What we need is double the resolve—an intensification of confidence.” (On moving forward): “When something goes wrong, look deep into yourself—not in an emotional way, to blame yourself or indulge your feeling of guilt, but to make sure that you start your next campaign with a firmer step and greater vision.” Moving forward I’ve learned a lot from mentors and colleagues throughout my career, but I also enjoy looking for inspiration outside of my normal work environment. Greene’s book “The 33 Strategies of War” provides great inspiration in the form of quotes, advice, and stories from history for approaching life strategically and rationally. Greene’s book is also very grounded and realistic in its approach, and he encourages us to do the same: “While others may find beauty in endless dreams, warriors find it in reality, in awareness of limits, in making the most of what they have.” Whether we are focused on our own research projects, maneuvering into the world in search of fulfilling work, or just going through our day-to-day lives outside of work, we will encounter different types of battles. Greene’s book focuses on the importance of goals in waging this war, whether they are personal or professional: “Do not think about either your solid goals or your wishful dreams, and do not plan out your strategy on paper. Instead, think deeply about what you have—the tools and materials you will be working with. Ground yourself not in dreams and plans but in reality: think of your own skills or advantages.” “Think of it as finding your level—a perfect balance between what you are capable of and the task at hand. When the job you are doing is neither above nor below your talents but at your level, you are neither exhausted nor bored and depressed.” How we approach them depends on our own strategy, but we can all face them with courage and strength by adopting a warrior’s approach to facing conflict. Greene’s discussion about internal warfare might be one of the books’ most relevant sections for graduate students. There are numerous quotes in this book and it’s difficult to highlight all of the great advice discussed in just one blog post, but to close off the post, here is a post on the importance of having a warrior’s heart: “It is not numbers or strength that bring victory in war but whichever army goes into battle stronger in soul, their enemies generally cannot withstand them.”

The origins of a super hero

(Spoiler alert: details of the plot of Wonder Woman in this section—proceed with caution!) I went to the cinema last Saturday eager to see Wonder Woman and optimistic that it would easily be one of my favorite superhero films. But after the film, I spent the entire way home on the tram complaining about the story to my husband. I’ll avoid extended discussions on my frustrations with films that feature breast-shaped armor for women and my other costume-related annoyances (I know it’s a tropical Mediterranean island…but they were fighting with swords and spears. Shouldn’t they be wearing pants or longer skirts that would actually protect your legs from getting hurt??). In reality, my frustration went deeper than the lack of proper clothing. I was disappointed with the lack of inspiration from Diana’s origin story in that I didn’t feel it was relatable nor realistic. “But it’s a superhero/fantasy movie!” you’re now thinking to yourself. “Of course it’s not real.” But just because the setting is imaginary, it doesn’t mean that the characters can’t feel real or can’t have a backstory that remind us of our own. Throughout the film, Diana was following her path towards achieving her destiny. She was brave, personable, cared about protecting people, and had a love of justice and doing the right thing, which are all qualities that we should strive for. But she was also the daughter of Zeus, trained from childhood by an island of Amazons for the purpose of defeating her half-brother Ares. For those of us who aren’t born the daughters of gods, how can our own origin story compare? From humble beginnings to…? Of the large number of talented, hard-working, and dedicated PhD students and early career researchers, only a select few will end up becoming tenure-track professors. The origin story of the PhDs who don’t end up with a tenure-track job will at first glance look the same as those who go on to be professors: a love of science, a natural talent or ability that leads he/she to a career in research, a dedication to our project, and the hard work and grit it takes to finish a dissertation. But the story doesn’t finish neatly there—at some point, for many of us, the path of our presumed destiny takes a turn. Turning off from this traditional career path leads us to a new type of beginning. We go from accomplished academic researchers, working hard on every experiment and fighting for every data point, to finding ourselves in an unfamiliar new working world. Any new career path means starting over: a new work culture, new buzzwords, new colleagues, and an overwhelming sensation that we are no longer the experts that we thought we were. Last week I embarked on my first day as an associate medical writer. I spent three years of life as a post-doc and felt that there was a place for me in the world of research. But after three years, I realized that following what I once thought was my destined path, of becoming some world-renowned/world-changing scientist, was no longer the path for me. I welcomed the opportunity to adjust my career trajectory and explore a new path in the area of medical communications. It meant starting over with a new commute, a new office, new rules, and a new hierarchy, all while becoming familiar with a completely new way of working. I may not have achieved what I thought had been my destiny, but starting over and embarking on a new path was something that I really wanted to do. Now I have the chance to embrace a new ‘destiny’, taking the lessons I learned on my previous journey while forging ahead to something unknown yet exciting. If you feel like you’re having a difficult time with starting over, or perhaps even knowing where to begin in writing your own origin story, here’s a few suggestions and things to keep in mind: Writing your own career origin story Embrace your passions and abilities. Our skills and passions define who we are more than the paths we choose in life. Part of finding the right path involves reflecting on what you’re passionate about. We all have a love or a fascination with science, but was it always connected to something else? In your research, do you feel the most inspired when teaching, writing, being creative, or helping others? A successful career is any path that leads you to feeling fulfilled and that puts your passions and expertise to good use. Finding this path is the true definition of success in a career. Superhero take-home message: Heroes who follow their heart are the ones who inspire us to do the same. Be ready to change your perspective. Embarking on any new path forces us to see things with a new pair of eyes. Even just moving to a new lab or getting a new boss provides us with new ways of working and interacting with colleagues. People who make the most of their changing career paths are the ones who are able to learn from their new perspectives and keep a broad look across the horizon. Be ready with an open mind to embrace a new way of working or thinking and you’ll gain as much from your new situation as you’ll put into it. Superhero take-home message: It’s not enough to follow your heart—you need to open your mind to new ideas and perspectives to be able use what you’ve learned. Find a mentor and an ally. Even a solitary hero needs trusted friends on his/her side, and very few super heroes ever work in complete isolation. In any origin story you’ll always find someone who falls into a mentor or teacher role. This is someone who helps the hero embrace a new perspective and progress through their story. Find a person along your path who will help you do the same, a person who will encourage you to work towards your passions while ensuring that you learn as much as possible. A strong mentor wants to see you succeed—so let them guide you, and at times push you, in order to help you get there. All superheroes need allies, so find someone along your career path who’s either been through the process or who is even learning alongside you. This ally can become your friend, your confidant, or just someone you can share your joys and frustrations with as you progress. Having a person who can empathize with your situation is a strong reminder that even when you’re struggling or you feel like you’re not getting something right, you’re not alone. Superhero take-home message: Even the strongest of super heroes can’t save the world on their own. All of us need people to guide us and to support us along the way. Failure is part of the learning process. We’re all driven by success and by feeling like we’re good at something. For those of us who always excelled in school, a failed experiment or a critical comment hits us in harder than we expected. But many super hero origin stories show us that even heroes make mistakes, both early on and even when they are at the top of their game. They stumble when trying to learn something new or find themselves unable to move forward when faced with a difficult challenge. Remember that critiques are not there to punish us but are there to help us learn and to make us better. Embrace your failures and strive to learn from them instead of fretting over them. Superhero take-home message: A hero gains more from what he/she gets wrong than what he/she gets right. Use every mistake as an opportunity to learn something new. We all have to start somewhere. Anyone who’s at the top of their field, be it a CEO, an institute Director, or a world-renowned researcher, wasn’t born into that role. They had to work to get to that position by starting at the bottom and working their way up. It’s easy to feel downtrodden if we compare ourselves to others without recognizing the potential of our own career stories and remembering that all origin stories have to start somewhere. Instead of comparing yourself to others, recognize that the starting point of your career is the part of the path where you have the most potential. Your actions and your attitude at this stage will help define how far you’ll go in the future. Take a deep breath and remember that even your first step, however small, is still a step forward. Superhero take-home message: Even in the most personal of origin stories, many heroes learn that the story is not just about themselves. Be ready to take a step back and see the picture from a broader perspective so you can better see your own potential for growth and progress. Finding (and becoming) your own hero Your career origin story is as unique and as varied as you are: it comprises your passions, your skills, the opportunities you embrace, and what you do with the challenges life puts in front of you. Perhaps I didn’t enjoy Wonder Woman as much as I thought I would because I’ve already found super hero inspiration from other origin stories. As my own career path changes trajectory from research scientists to technical writer, I find myself attracted to stories where the hero finds himself or herself in an unexpected place but uses his/her skills, passions, and fortitude to progress and excel. And what’s even more inspiring than tales of fictional super heroes are the people I’ve met who have shared their career transition stories, who took advantage of new career paths and opportunities and found a great place to work that brings their skills and passions together every day. No matter whose stories you consider inspiring, or what your own path looks like, remember that you can also be your own hero. Whether you’re working hard to find a career that’s the best fit for you, or you simply find yourself on an unexpected detour, your origin story can become one that’s worth telling. No armor or capes required!

Are you up to the challenge?

If you’ve seen any advertisements for martial arts schools, you’ve likely noticed how the various forms of martial arts are all touted as ways for a person to gain self-confidence and self-esteem. Given the fact that I already have a black belt and am now approximately one year away from earning a second, you would think that confidence would be no problem, that I’ve already gained perfect self-esteem from earning a black belt. How could I ever lack confidence? After nearly three years of tae kwon do training in Liverpool, I now have a new club and a new coach. Stepping into an unknown dojo where the warm-ups, stretches, and drills are all new is a humbling experience when you get to a moment where you feel like you can’t keep up with everyone who knows the routine already. It’s left me feeling less confident in my abilities than the month before and more frustrated when I got things wrong. Even with three years of training and a red belt, I still suffer from waivers in my own self-confidence in the sport. There are many experiences as a PhD student or early career researcher that can cause our confidence to waiver: a rejected grant, a scathing comment on a manuscript review, or a failed experiment. We all face challenging moments that shake our beliefs in our own value or skills. Having strong self-confidence is one of the ways that we can work through challenging moments as we keep our head held high and our mind in a positive place. In this week’s post we’ll discuss the importance of self-confidence and the steps you can take to unveil your own inner champion. The basics of confidence Confidence is touted as one of these all-important facets of life, as something that we all need to have. But does anyone really know how to get it? Is it learned or inherited? How does one learn to be confident? Similar to the concept of networking, confidence is a nebulous concept that feels difficult to acquire. The Oxford dictionary lists the first definition of confidence as: “The feeling or belief that one can have faith in or rely on someone or something.” For this post, we’re more interested in the secondary definition: “A feeling of self-assurance arising from an appreciation of one's own abilities or qualities.” In other words, confidence is the resounding voice in your head that tells you “I can do this” and when you hear that voice, you believe it. But let’s approach this more scientifically. We shouldn’t believe that voice without empirical evidence—we need proof of our own abilities, not just belief in them. Thankfully in academic research, empirical metrics are everywhere. It’s why we care about endpoints like the number of papers we published, how many citations those papers have, who comes to our talks, how many grants/awards we receive, etc. We put value on our tangible accomplishments, all listed out conveniently on our CV. So if they’re all listed out and we can count them and read them, it should be easy to gain confidence from them, right? This is only true if we appreciate our achievements, our abilities, and who we are as people and as researchers. We can have a CV filled with papers, book chapters, and awards yet can still feel like we are not good enough. This is evident when talking about imposter syndrome, a situation where regardless of the number of achievements or accolades, you discredit yourself and your work entirely. The trick is that confidence cannot be imparted on you externally—no number of papers or awards will make you more confident. Confidence has to come from within. How do you gain confidence? Building confidence cannot done in a single day of soul-searching, but it’s something that you have to work on continually. Confidence is also ephemeral; it can wash over you and make you feel as if you’re invincible, or it can quickly recede and leave you feeling vulnerable, just like I experience in own waivers of confidence associated with tae kwon do. Martial arts emphasize the importance of the mental components of the sport, such as meditation, courtesy, and respect, at the same time as teaching you physical skills. But the key to finding confidence in a sport, or any activity, and even in your own career, is you. Anytime I go to a tournament or test for a new belt, I get nervous. I see the other people I will fight against or the high-ranking black belts who will judge my performance. It’s not enough to look down at my red belt and see my achievements with my own eyes—I have to feel them, too. Your own path to self-confidence will be very personal, but if you’re looking to make steps in a positive direction, here are some ways that you can work towards breaking down the barrier between seeing and believing in yourself: Find your passion. In your own career, you will find that a love of science or research doesn’t necessarily translate into a passion for every aspect of the job. You also won’t be naturally gifted at every part of your work. To help build confidence in the early stages of your career, find and focus on the part of your work that you love the most and use this as a central focus of your confidence-building activities. For me this focus was (and still is) writing. I used writing as a way to gain confidence in the rest of my project. It was a way for me to collate thoughts and ideas before taking them to a place where I had less confidence, like a platform presentation or a committee meeting. Writing helped me realize that I did know what I was talking about and gave me an opportunity to do something I liked while also improving on the other parts of my work, like public speaking. Keep your level of confidence steady through both ups and downs. Although your confidence will inevitably shift when faced with the positive and negative events of your situation or career path, work to avoid the extreme ends of the spectrum (either a complete lack of confidence or over-inflated self-worth) by finding your center ground. From this position, you can use positive situations to propel you further, but be sure to stay within reasonable bounds. One published paper won’t lead to a Nobel prize, but it is a worthwhile achievement and worthy of celebration. On the other hand, one rejected paper is not a complete step down from your center ground, but rather a chance to take the positive part of a negative situation and to learn from what went wrong the first time. Failures are one of the best ways we can gain fresh perspectives and to improve our work for the next submission. Practice positive thinking. In science we are surrounded by critiques and reviews of our work, and many of us will internalize these messages as well as adding a few negative ones of our own. Being self-assured in your own qualities and abilities involves injecting optimism into your internal dialogue to help offset the critiques that come with a high-achieving career. Positive thinking doesn’t have to be cheesy or fake, and you don’t need a pair of pompoms to be your own cheerleader. For example, positive thinking can provide a positive spin to negative situations (“The rejection was pretty tough, but the reviewer makes good points that I can incorporate into the next draft”) or can help you envision a positive outcome instead of dwelling on a negative one (“I’m nervous for the talk, but I’ve practiced it enough now that I know I’ll do a great job once I get on the stage!”). I am not a naturally optimistic person, especially when I get nervous. One approach that I use is to change the situation when I’m surrounded by my own negative thoughts. I text a friend or call my husband to vent my nerves to someone else or to simply change the topic. Even turning on some upbeat music can help shift your mindset when you find yourself in a funk. If I am nervous for a talk, a meeting, or a tournament, I turn on some Sia or Madonna to put my mind in a better place. Shifting your situation can help improve your mood and broaden your perspective, opening up your mind to positive thoughts instead of negative ones. Remember that failing doesn’t mean you’re a failure. Failing is an essential part of any career and is also a facet of becoming an expert in any sport, skill, trade, or activity. Unless you are a prodigy, trying something new or beyond your current skill level will involve various degrees of failure. Becoming self-confident means facing a potential failure with cautious optimism: cautious in that you know you need to try your best, but optimistic in that you believe you can succeed, even if you fail the first time around. Another important thing to remember is that coaches and mentors give critiques specifically because they want to see you improve. In general, people who seek out careers as professor want to see their students and their mentees succeed. Your mentors know that you are the next generation of scientists, and their critiques are there to help you, even if they are offered in a rather blunt or direct manner. You should also recognize that when people criticize your work, they are critiquing your output, not you as a person. Becoming unstoppable Confidence is not an easy thing to obtain. The keys to building confidence are to stay grounded, explore new skills and tasks while highlighting on your passions and abilities, and work to maintain a positive outlook. When good things happen, maintain a steady disposition and find productive ways to cope with failure, even if it means a short change of perspective or distraction from the situation. Once you begin living life with confidence, it will be difficult for any challenge to dislodge you completely. You’ll find that the challenges don’t last forever and the critiques only serve to fuel your internal flame.

“So, what are your plans for after you finish?”

It’s no secret that being a PhD student is stressful. Thankfully the process of earning a PhD doesn’t last forever, but because of its finite nature, any conversations with friends or colleagues will lead to the inevitable question of “So, what’s next?.” My group of colleagues includes some final year PhD students, all of whom are facing a not-too-distant future of writing and defending their dissertations. On top of this pressure, they are also worried about their job prospects and transition from student to employee. When I finished my PhD, I was fortunate enough to have a prospective post-doc offer not long after finishing my dissertation. I managed to pass the time between submitting my dissertation and graduation without any additional job search stress. But I didn’t escape the job search stress for very long—last spring, and after many months of uncertainty about extending my post-doc contract, I found myself scrambling for what to do next. I applied for 9 jobs, and even landed an interview for one of them, but nothing fruitful came out of my search. I took a deep breath of relief when my contract was officially extended, but the experience left me with two realizations: 1) I was very lucky to still have a job, and 2) I would be in the exact same position again in 10 months’ time if I didn’t do something differently. The importance of a professional network Part of the reason for my struggle during my initial job search was that I only sort of knew what I wanted to do, which at the time included anything related to science communication, publications, public engagement, and so on. I knew that I didn’t want a career as a researcher, but I didn’t know what my exact options were or how to get there. What would an application reviewer be looking for on my resume? What sorts of skills did I need to highlight that were not on my academic CV? What types of positions could I realistically aim for with my skills and experience? I had a lack of understanding since I had only recently decided what I wanted to do after my research post, and because I was new to the area I also lacked an existing network of colleagues and potential mentors working in the field that I wanted to enter. From my time as a researcher, I had a vast network of academics as well as industry and government researchers, but I didn’t know anyone doing science communication or writing. I had a broad understanding of where I wanted to go, but I was walking there blindfolded. We discussed in a previous post about the nebulous nature of networking and some approaches you can use to make connections. Before we go further in this post, it would be good to revisit the definition of a network once more. Simply put, your network is the set of connections you have to colleagues, friends, and family members. These are connections you’ve made on a personal level: it’s not just shaking someone’s hand at a conference but means having a working relationship with them. They know who you are, what you can do, and your passions and area of expertise. Networking may not seem that important if you are in the midst of lab work or writing your dissertation. But a solid network with more than one branch can take you places that wouldn’t be possible by simply sending in job applications and hoping for the best. Networking can show you hidden opportunities that won’t always be advertised and your mentors and connections can help you figure out how to enter into a new area by helping you to highlight your relevant skills or lay out a job-specific resume. But there’s a trick to networking: because your network represents your relationships with other people, it’s not something you can put together on a short notice. You need to establish your network early on in your career so you have time to work with and establish trust between you and your connections. The key is to build trust with others before you need something from the other person—like a job, for example. Where should I start? 1) Identify your skills, professional interests, and your long-term career goals After going through contract extension panic, I realized that I wanted to pursue a career in science communication. But my short stint of job applications made me realize that this was a very broad ambition, and I felt like I was spreading myself very thin trying to cover every aspect of what this type of career could entail. One of the ways I narrowed my career target was by reading Born for This and going through the book’s exercises. Perhaps the most powerful exercise in the book was when the author told us to think about what other people ask us to help with the most. This is a way of showing us what we’re good at because it’s something that others ask us to do for them. I realized that over the course of my time as both a PhD student and post-doc, I helped others the most with writing. Sometimes it was reviewing articles or manuscripts, other times it was in taking the lead on a paper that had been sitting unwritten for too many months. This exercise helped me realize something that was both a passion and a skill, which then helped me focus on careers related to writing. 2) Rework your brand Knowing that I wanted to look for writing jobs, I sought out more opportunities to write. I participated in writing contests and guest posts for blogs and University websites. I then restructured my CV to highlight my written work more strongly. I also took part in writing classes (Coursera has some fantastic online courses if you’re looking for something free) and made sure that my social media profiles were up-to-date and reflected my career goals. It sounds like a lot of work, and I did spend a good deal of time working on this outside of my normal post-doc hours. But it was also very enjoyable—I enjoyed learning about new topics and I got to meet other like-minded people in the process. This should also be a part of your re-branding process; if you’re not having a good time being the person you’re working hard to become, you should reconsider the path you’re walking on. 3) Look for opportunities that fit your style and your needs Once you have your career goal and your brand figured out, start looking for what options you have based on your current/future limitations. For me, I knew that my husband had a job offer in Manchester for two years, so I wanted to look for science writing/communication jobs in that area. While looking at jobs on LinkedIn I found several posts for medical writers, and there were a lot of entry-level positions in the Manchester area. I soon discovered a field, of which I had never heard, that was looking for PhD-trained researchers right in my back yard! I followed up by looking in more detail at the job advertisements, finding some resources about the field online, and sent off my resume for a couple of posts even though I didn’t need a job at the time. I felt that I had struck gold, but knew that it would take more than a good looking CV to get me my first job in a new area. 4) Look for connections that can help you reach those opportunities Last autumn I was busy trying to get lab work finished so I could make more progress on the final manuscript for my project. One afternoon I found myself chatting with a PI in the physiology department whose lab space I used for some of my experiments. He knew that I was getting towards the end of my post-doc contract and asked if I had plans to stay in research and I told him I was looking to make a transition into the medical communications industry. As it turned out, the PI had a friend who was working at a medical writing firm near Manchester. He offered to pass me along his contact details and even to put in a good word with me at the pub when he met his friend for a drink later that week. This conversation was a lucky exchange but one that highlights the importance of having trusted connections in all parts of your work. I was only working in this lab part-time and had no interest in continuing that facet of my work, but the PI knew I was hard-working, organized, and creative. He soon passed along his friend’s contact details and I made the all-important initial contact: a request for an informational interview. I didn’t ask this new contact for a job or to look at my CV, since at the time he was only a colleague of a colleague. In my initial exchange I asked if we could meet informally to discuss more about medical communications in general. My goal was to meet someone in the field and hear from them what the work was like, then later on to expand this relationship and work towards getting help structuring my CV or even hints on potential job posts. This was all starting to happen close to six months before my contract would finished, so I also didn’t need anything explicit during our initial contact. PS: If you’re looking for tips on what to ask during an information interview, be sure to check out Alaina Levine’s “Networking for Nerds book-it’s a great read! 5) Pursue opportunities as they come The informational interview that I proposed never actually happened. As it turned out, the company was recruiting for an associate medical writer, and my new contact asked for my CV right away. I was nervous to send off my CV, but the work I had done restructuring my resume and highlighting my writing-oriented skills paid off. I was then given a writing test and made sure to not take the effort lightly even though I didn’t need a job at that time. I learned more about what was expected and dedicated a set amount of time to working on the test. One successful writing test and one in-person interview later (with my new contact at the other side of the table), I found myself celebrating the new year with a job offer to my name—months ahead of schedule! Writing your own career story My own career story was the result of yet another stroke of luck. But sometimes luck isn’t just a random coincidence: luck is something you can make for yourself. Sometimes luck is a product of the time and place you’re in. Sometimes luck is an opportunity you didn’t plan for that ends up directing your life’s story. Luck, timing, and the ability to find and seize opportunities leads us to many paths in our careers, and it’s often on these unplanned roads that we find the way through our own career journey. But in order to take advantage of the hidden opportunities that can lead to game-changing moments, we need to network. This involves having strong personal connections with a wide range of colleagues as well as a solid and trusted reputation that connects to your name. Networking might seem like something nebulous or far-off while you’re knee deep in your own research, but thinking about your own career path as well as what connections you need to get there can take away part of the stress and uncertainty of your job search. You might not instantly have an answer for the question “So, what are you doing after you graduate?” but at least you’ll be able to say with confidence: “I’m exploring my options.”

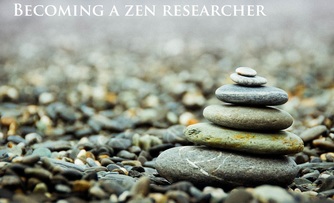

On Sunday night my husband and I returned home after a 10-day trip across South Korea and Japan. At just under one thousand pictures across six cities and two countries, the trip was incredible—but also exhausting. With an itinerary full of hikes, sightseeing, early train rides, and the inevitable jet lag, we arrived back home more or less worn out. There were times on the trip, especially our long 21-hour travel day back home on Sunday, when I thought to myself “Why don’t I take more relaxing holidays?”

Halfway through our trip, we flew from Busan at the very southern tip of South Korea to Kansai airport in central Japan. A 6am taxi pick-up, followed by a 1 hour drive across town, followed by queueing for check-in, security, the border control, and finally the plane ride, left us feeling a bit exhausted by the time we made it to Osaka. But a comfortable express train brought us to one of my favorite places in the world: Kyoto. The soft October sun and the touch of red in the maple trees greeted us to the city and I soon forgot the exhaustion required to get there. Our first stop was Kennin-ji, my favorite temple in Kyoto. It’s a large complex that sits in the middle of the city. Despite a busy day with swarms of tourists wandering all over, the temple itself was rather quiet. It felt like we had the 800 year-old wooden hallways and painted panels all to ourselves. My husband and I scuttled around in shoeless feet with the scent of incense and a warm autumn day surrounding us. The temple was in itself another moment to reflect on the trip so far, of the incredible moments instead of the exhaustion or the travel details. The breathtaking mountainside temples just outside of Seoul, the relics of the Silla dynasty in the 1500 year-old capital Gyeongju, and the sunny beach-side breezes while walking in Busan. And of course all of our adventures (and misadventures) were followed by warm nights spent outside while enjoying spicy soups and delicious barbeque to refuel after long days of walking. Many of the places we visited on the trip were Buddhist temples. Buddhism includes a range of sects and branches, many of which were hard for me to keep track of after the numerous temples and shrines we encountered. Zen Buddhism was popular in both Korea and Japan and emphasizes the importance of hard work to its followers. They see hard work as a path towards enlightenment, and had the foresight to bring over tea from China to help give their followers the energy they needed. A job as a researcher involves a lot of work, and at times a lot of stress, but it also brings great reward. The elation we feel when our work is finally published comes from the knowledge of what it took to get to that point in the first place. The joy we share with our colleagues when we get a significant result after weeks of troubleshooting comes from the journey we took to get that result, not just the result itself. And as much as I enjoy the more relaxing parts of a holiday or the end of a long a work day, I can see where those Zen monks are coming from—there’s a lot of joy to be had from knowing a good day’s work has been done. I’m certainly not yet a Zen Researcher and am still looking for ways to achieve Research Nirvana instead of feeling weighed down by the long days or the stressful moments. I’m also certainly not a Zen Traveler either, as I still get stressed out by early morning train rides and rainy days on my holiday. But what I do try to do in both my career and my life is to enjoy the rewarding moments as they come, to focus on them instead of the stress that led you to them. Let the joy of a well-earned view on a hike, a hidden mountainside temple, or an accepted paper provide the fuel you need to keep working towards the next milestone. For me, achieving Zen as a researcher is a constant effort to find the balance between work, life, and everything in between. Since finding a balance requires knowing how much weight to put on either side, I encourage you to weigh the rewards and the challenges of your own hard work, however large or small they might be. And just as the monks saw the value of tea for their efforts, don’t forget to include a bit of caffeinated assistance as you continue on your own journey towards achieving your goals—although we might recommend coffee over tea for a stronger effect! World mental health day: Coping with stress, anxiety, and the rigors of a researcher’s life10/12/2016

Some Mondays end up being more Monday-ish than others. This week started with a particularly Monday-ish Monday, not in that any one thing was extremely challenging or upsetting but that it felt like things kept piling on. I woke up reading the commentary on the previous night’s dreadful excuse for a US Presidential debate, which itself came after a weekend of voiced concerns on Facebook and Twitter about brushing off comments made about women as “locker room talk” or “alpha-male banter.” Not to be one-upped by America, of course, the UK decided to fan the Brexit furor, this time discussing how to “name and shame” companies that hire non-British talent. In theory, companies would have to disclose how many expats (like me) they hired in the thought that sharing this information would be a disincentive. This would in theory include almost every university here in the UK, not to mention countless other research institutions here. The combination of this acrid news from both of the places I consider home, combined with work deadlines related to collating comments on a manuscript and dealing with freezer repair logistics, turned the start of this week into the epitome of a Monday.

Stressful situations, even if they are just another Monday sort of Monday, can lead to self-doubt, anxiety, and imposter syndrome. They can bring out frustrations or worries that in a normal day might go unnoticed. It’s for this reason that World Mental Health Day is such a crucial day to remember, especially for those of us in the academic and research sectors. We are constantly being judged by our results, critiqued by our reviewers, and wondering if and when the next job, grant, or statistically significant result will finally arrive. These may all reflect the reality of just another day in the office of an academic researcher, but when this day is compounded by either external stresses from outside of work or internal pressures that you set on yourself, stress can become a real problem. I am fortunate enough to not have experienced many significant external stressors in my life. Apart from the occasionally Monday-ish Mondays, my life treats me very well. I have a wonderful husband who supports me every day, friends and family who look out for me on a regular basis, and I’m in good health with some savings in my pocket. I know this is not the case for many people and I won’t pretend that “I know your pain” or try to convince you that this blog post can make everything better. But what I do struggle with, and what I imagine other researchers might also empathize with, is a large amount of internal pressure that I put on myself, pressure that can occasionally build up to unhealthy levels. I’ve seen a lot of PhD students and aspiring academics/researchers who have similar personality traits. In general we tend to be organized, Type-A individuals, the ones who sit in the front of the classroom with a fleet of colored pens for taking notes and who already know the answers to every question. Because of the nature of our work, we also tend to be very independently driven. We’re the ones that don’t have to be told to do something in order to do it. It’s the reason we publish without submission deadlines and finish lab work without a boss telling us exactly what to do. This is a great trait to have as an academic, but feeling like you’ve always got to do something can leave you with a classic case of academic guilt: no deadlines or bosses, but always something you just have to do. As an undergraduate student, I was the one who made her own color-coded flashcards and began essays as soon as they were assigned. In graduate school I published two first-author papers, won numerous presentation awards, and was the ‘golden child’ of my lab, one who could never seem to do wrong. I was driven, always busy during the day while keeping up with emails and volunteer work in the evenings. I felt like I had a decent work-life balance, I didn’t go to lab every weekend and I took time off to visit family and to travel. But even with breaks, I’m a person that is almost always on. There’s always something to do, something to do better than before, something to think about, something to get ready for. This mindset has been useful in keeping me on top of my work and my career as a graduate student and now as a post-doc. It works when everything around me is going well, but when something cracks on the other side of my internal pressure gauge, I burst. When I was faced with uncertainty in extending my post-doc contract, I found myself torn down by panic attacks and overwhelming feelings of despair and self-doubt. When I was struggling with conflicts or loss among family and friends, I found myself unable to relax or enjoy life. When I was stressed about an upcoming deadline or meeting, I found myself stuck in an endless loop of working on a problem for so long that at some point I’d realize that I had just been staring off into space for several minutes not really working on anything. I’m sure I’m not the only person who has run into problems with anxiety and stress, especially when work and life gets confounded or when they become out of balance. It’s hard being self-motivated when our way of working through problems is to keep working -- even when it’s detrimental to our work, our lives, and our mental state. While there’s no simple solution to the problem of how we deal with stress and work-life balance, here are a few pointers which have helped me face the past few months with a bit more calm and resolve: Let yourself disconnect and refocus. It’s hard to disconnect when email comes to your phone and the problems of your day seem to sit in your mind all evening long. One way to help this is to find a place in your day or in your week when you allow (or force) yourself to disconnect. My favorite part of the week for refocusing is tae kwon do class. It’s an hour-long session twice a week where my phone is off and my mind is set at the task at hand, which is no longer emails or data analysis but stretching and sprinting. I get to take all of my frustrations and channel them into punches and kicks, and at the end of the class I feel refreshed and refocused (also sweaty and exhausted). Martial arts aren’t for everyone, but seek an activity that suits your style that lets your mind do the same, be it a yoga class or a glass of wine in your bathtub. Mourn or get mad, and then try to move on. Let yourself be sad or upset when things are tough instead of trying to convince yourself that everything is OK. Listen to your favorite angry song when you have a bad day or cry out your story over the phone with your best friend. It’s healthy to let yourself be upset by things that are upsetting. But a key point in picking yourself back up again is to try to move on from the situation. Listen to your angry song and then pick a motivating/upbeat song to help switch your mood to something more positive. Cry out your story to a friend and then watch a dumb video on Youtube that makes you laugh. These moments of transitioning between emotions can help give us perspective: yes, life is upsetting, but it also moves on, and so can we. Have a network of people looking after you. Regardless of what sector you work in, you’ll meet a lot of types of people. Unfortunately one of those types of people will be jerks. People who are only looking after their own interests alone or who are mean, rude, or otherwise unsavory to be around and to work with. I get really frustrated by jerks, to the point that it can bring out my anxiety and stress as much as a hard day at work can. Because of this, I take comfort in having non-jerks by my side with whom I can talk to when I feel like the jerks are taking over the world. Especially as a PhD student and early career researcher, having a network of positive people around you, people who support you and value your career/professional development, can make all the difference. Treat yo(ur)self! In a career that’s full of critiques and judgements about your work, learn how to be your own cheerleader. It’s good to stay motivated to keep working hard, but not at the expense of your own self-confidence. An easy way to do this is to learn how to celebrate the good, no matter how big or small it is. Did you finish editing a paragraph of a boring manuscript? Congrats! Make a second coffee and scroll on twitter for 10 minutes. Did you finally submit your dissertation? Congrats! Tell all your friends and coordinate a time for drinks. Part of finding a good balance with mental health is to learn how to reward yourself instead of always looking for things to be done, fixed, or improved upon. Don't weigh your self-worth on external metrics. It’s easy to spend time comparing ourselves to others or getting into the mindset that we just need another paper or award and we’ll finally feel good about are accomplishments. Rewards won’t always come and it’s easy to look at someone else’s life on a piece of paper or online and think that they’re much better than we are. Put value in yourself by things that don’t have an external measure to them. Don’t rely on citations, Twitter followers, or the job you have right now to be the only things that define you. Your skills, your passions, your experiences, and most importantly you as a person have self-worth on their own. I’m happy to have ended this week’s Monday on a good note, thanks to a good tae kwon do class followed by a session of night-writing. While I write this blog for graduate student and early career researchers primarily, in a way it’s also a place for me to speak to myself and to try to reconcile my own frustrations and stresses. But hopefully this blog isn’t just me talking to myself but can also help you find your own way forward through the rigors of an academic life!

It’s never a good sign when your day starts with over 200 unread Whatsapp messages. Last Friday (June 24th), I woke up to news that I and my friends on the Liverpool Whatsapp group had thought would never happen: the UK had voted to leave the EU. Even after the initial whirwind round of messages sent in the early morning hours, the rest of the day was spent reading news articles and seeing the shock and disappointment from UK and European friends on Facebook and Twitter. With the flood of posts swirling around in the past few days, I wanted to take the time and think about what Brexit will mean in the context of the type of work that binds me and many of my UK and European friends together: science.

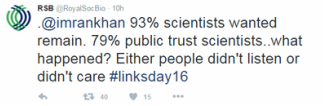

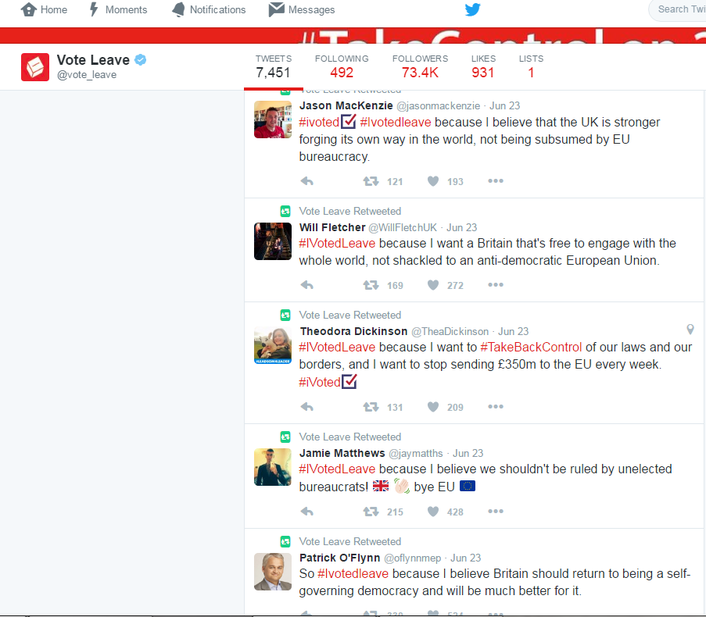

There will be numerous direct effects of leaving the EU on science here in the UK, on everything from the availability of grants, the mobility of professional researchers, and the scientific infrastructure that’s been set up within the EU. As I read these articles and numerous other ones like them, I empathize with my friends who are in the process of developing their own careers in science here. How can you manage additional uncertainties in a field where you already have to spend so much time worrying about grants, short-term contracts, and competitive jobs? The flood of news articles and opinions continued to pour in over the weekend from experts and scientists, but after being drained of my productivity on Friday and worrying about the implications of Brexit on my own future, I took a break from reading the news this weekend. Even so, one of the article subtitles kept me pondering the rest of the weekend: ‘What has the EU ever done for us?’ This question brought me back to the Life of Brian scene, where while planning an uprising against the oppressive Roman regime, the question is brought up of what, exactly, the Romans ever did for us. “... but apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order... what have the Romans done for us?” Romans have now come to mind a second time on our blog and for good reason. During my travels around Europe, I’ve been able to visit 16 of the other 27 EU countries, and only 9 of the 28 EU countries (still counting the UK) were never a part of the Roman Empire. In the many places I’ve visited around Europe, I’ve seen enduring remnants of Roman building projects. From the state history museum in Budapest, full of Roman artifacts found across the Hungarian plains, to the impressive and fully intact aqueduct of Segovia, and Hadrian’s Wall just a couple of hour’s drive from Liverpool, stretching across Northern England and still marking the boundary between what was Rome and what was the rest of the world. Rome was certainly not a perfect empire, but it was one that lasted for over 300 years. This is impressive for a relatively unconnected world as compared to ours, in a time without telecommunications or any transport more rapid than the horse. Even still, Rome was connected across the vast amount of land between its borders, and people were Roman despite where they had been born, what language they spoke, or how exactly they came to be incorporated into the Empire. While I’m sure not everyone had a fantastic life under Roman rule, and there were certainly a fair share of bad emperors throughout the history of the Empire, Rome as a unified concept did mean something important. As a person living in the classical period and regardless of your income or your social status, you would have been able to see the positive impact that a road or clean water had on your life. You would have enjoyed plays in the local amphitheater or the wines and exotic foods more easily available to you and your family from across the empire. You would have felt some protection at being part of a bigger unified nation than when isolated to just your village or your tribe. Being Roman 2000 years ago would have meant being part of something powerful, something beneficial, and something enduring. But as we already know, Rome didn’t last forever. The empire fell and the Western world left with warring neighbors, short-lived empires, and a period in history that came to be known as the Dark Ages. I don’t believe we’re headed for another dark age, but as history shows us we do need to recognize that history involves cycles of uprisings. But unlike the Dark Ages, we have countless sources of news nowadays, we can get facts and figures from reputable sources, and we can hear directly from experts in order to get a better understanding of the problem using sound logic and reason. Right? As we discussed in our storytelling post two weeks ago people tend to rely on emotions when making decisions. With money, a family, and a future on the line, people are not always driven by logic, facts, and figures. We are driven by emotions, by stories, and by selfish needs. Unfortunately, the Leave campaign made good use emotions and fed off the enthusiasm of an uprising, bringing together a rousing rally against ‘the man’ (e.g., the EU) that’s apparently holding us back. This line of campaigning is evident from the tweets on their twitter account and you can see a few of the tweets below:

Oddly enough, there’s no equivalent @Vote_Remain Twitter account, and while there are a flurry of #Remain tweets (especially now after the vote is over), it seems that the question of ‘What did the EU ever do for us?’ wasn’t as enthusiastically addressed by the Remain campaign.

But what does this all mean for scientists? In the midst of worrying about the future of our research contracts, the prospects of losing future EU grants, and thinking our colleagues who come from every side of the world to work in the UK, we also have to recognize that in this day in age, scientists are considered ‘the man’. In a campaign that has won by fueling disregard and mistrust in ‘experts’, is it any surprise that people started to go against the recommendations of said experts? Scientists are not considered to be of a trustworthy profession, and we come off as competent but not very warm. In a recent study conducted in the UK, one person relayed this comment on why they had no interest in science: “Snobs, know it all! Better than others just because they are intelligent, boring and thinking everyone should know what they know!”. Is it then any wonder that in an age where people are taking a stand against the status quo and ‘the man’ that this also means a stand against science? If scientists want to stop being ‘the man’ that the rest of the world is up against, we need to think about and engage in the communication streams that people get. While most of the other respondents did have a general interest in science, many felt that scientists were hard to access. Events like science fairs and festivals look great on paper or on a resume, but many folks are limited in their ability or interest to take time from their own lives on a busy weekend to go and do such an activity. Many are engaged with science news in the media, but since the media also has the potential to get something wrong or to over-sensationalize something, how can we as scientists do better to share our science? If people feel like we are hard to communicate with unless we come to them in a science fair, why should we expect them to trust us as the experts when we say to them from afar ‘if you do X then Y will happen, so you shouldn’t do X’. Now is a good time to reflect on how we as scientists can do a better job at not being seen as ‘the man’ but as a member of this team, of the metaphorical Rome that is our world. Based on the results of this survey, it’s not that people have no interest in science or don’t see value in what we do, but that we’re not meeting people where they are, that we’re still stuck in ivory towers pondering all our expert opinions instead of meeting them face to face. We can spend our days post-Brexit worrying about our own grants and jobs, or blaming the other side for whatever happens next, but in a few years’ time the dust will settle on the UK’s exit from the EU, and we’ll still be ‘the man’. If we focus on getting people on our side by talking with them eye-to-eye and making them part of a two-way discussion, we can make sure that we narrow the gap between The People and The Experts. If we meet with and have discussions with people outside the ivory tower, if we engage in listening instead of lectures, we can make connections and we can build trust. Regardless of the future of the EU, the UK, and everywhere in between, we as scientists still continue to have the power to make great and positive changes in our world. Just because history tends to repeat itself, it doesn’t mean we have to repeat it completely. We can learn from how to connect with people by listening to what fuels their interests and where they want to engage with us. We can change the personal of scientists from being cold-hearted and nerdy towards a more accurate depiction: we are hard-working, motivated, and we are here to make the world a better place for everyone. Despite the turbulent times that we find ourselves in, I am encouraged by the fact that people do have an interest and are looking for information when they make decisions about their lives. And if history teaches us anything, it’s that even though Rome eventually fell, after the Dark Ages came the Renaissance. After having seen first-hand the relics of Rome spread across so many countries, I’m encouraged and hopeful that the relics of a united Europe and a united world will last well beyond our lifetimes. SPQR!

With one and half days still remaining in the SETAC Nantes meeting, I was exhausted by the lunch hour on Wednesday. I had presented in an early morning session that day, had spent the previous two days in meetings and filming a promo video for the next SETAC science slam, and was dreaming of caffeine on a regular basis. That being said, I did feel good knowing that the next day I had an evening flight to Marseilles for an extended weekend in the south of France. Just then, a text message from RyanAir informed me that my flight was cancelled because of strike actions by air traffic control. It was a bit of a drag, but soon enough I was re-booked for a Friday trip to Perpignan and re-invigorated with the chance of spending a weekend of wine and sun after four days of conference-ing.