I’m taking a break from the blog both this and next week to focus on some other writing projects, but in the meantime I thought I’d delve into the archives of my personal blog I kept while a graduate student. This one was one of my early attempts at science communication and focused on a restored lake which was in the middle of the University of Florida campus. Nice to have a bit of a walk down memory lane to remember the good times in The Gator Nation. Enjoy!

“The Story of Lake Alice: Finding the right balance between nature, administration, and aesthetics” Originally published on "A toxicologist's tale", 11 Sept 2012 5pm rolls around and you’re more than ready for the end of the day. Whether your day is spent in class, at work, teaching, or doing research, we all need a place to unwind after a busy day here at UF. Many of us seek out natural areas to cleanse our minds and bring perspective to the tumultuous moments we go through each week. For many students and staff, the hallmark oasis of these natural areas on campus is Lake Alice. It’s a place for relaxing walk with friends to look for alligators and soft shell turtles, for a vigorous jog through the winding trees near the Baughman center, or for waiting patiently at the bat house for dusk to fall. Lake Alice provides us with so many easily accessible and engaging ways to enjoy the many pleasantries of nature. But perhaps on occasion you’ve noticed things that made you wonder just how pleasant these natural areas on campus really are. Maybe a powerful smell as you jog along the north shore, the extremely turbid waters in the creek at Gale Lemerand and Museum Road as you walk downhill to the commuter lot, or the incidences when the whole lake turns bright green. You’ve likely asked yourself what these events mean for our lake, if our lake is as clean and healthy as it should be, and if you should be concerned about any of it. But before jumping into conclusions about how healthy our lake really is, we need to take a step back and understand how the quality of water bodies is defined and the numerous roles our treasured Lake Alice holds for our campus. Lake Alice has a rich and varied history since the lake and the land around it was purchased by UF in 1925. At that time, the only sources of water input into Lake Alice were rain, storm water runoff, and untreated sewage. As UF continued to expand, the direct input of sewage into the lake was no longer seen as a sustainable option, so treated effluent was discharged starting in the 1960’s. In 1994 the Water Reclamation Plant was built, and now the treated effluent is no longer discharged directly to the lake but is piped to one of Lake Alice’s discharge wells. Lake Alice currently receives water from stormwater and irrigation runoff that enters from the connecting creeks. Lake Alice is not here only to serve as a oasis for us: Lake Alice and the other lakes on campus are also the official storm water retention ponds for UF. These on-campus lakes are under the regulation of the federal government as part of a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit that the university holds. Holders of these permits are required to identify and prevent non-point sources of pollution, which includes things like irrigation chemicals and contaminated runoff from roads near the lake and connecting creeks. As part of the broader plan for waters on campus, UF also wants to help Lake Alice reach Class 3 water quality standards for the state of Florida. Meeting these criteria would mean that the lake is suitable for “fish consumption, recreation, propagation and maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife.” Lake Alice is also a recognized conservation area (so no fishing or swimming allowed, even if the lake does meet Class 3 standards) and it serves as home to over 75 plant species and 60 animal species—including our university’s mascot the American Alligator. With all of these different functions and regulations—storm water retention area to the federal government, a potential Class 3 water body for Florida, and a wildlife conservation area—how is UF keeping up with the array of unique demands from administration and nature alike? One approach to monitoring if these demands are met was by the establishment of the Clean Water campaign in 2003. Dr. Mark Clark, one of the founding members of the campaign and a professor of the Department of Soil and Water Science here at UF, is currently overseeing the outreach and public awareness efforts of this group. These activities include installing drain markers to inform people that campus drains flow into Lake Alice, volunteer clean-up efforts, and educating the public on water quality issues. Another major facet of the Clean Water campaign is monthly water quality sampling events that have taken place since 2003 at 20 locations all over campus. Some of the locations include the creek near the New Engineering Building, Hume Creek in Graham woods, and the Baughman Center bridge. Based on the water quality data collected so far, there are two main chemicals that have the potential to cause problems for the competing regulations imposed by administration and the natural requirements for having a healthy lake: nitrogen and phosphorus. Both of these chemicals can cause algal blooms and plant overgrowth as well as decreased oxygen levels. Decreased oxygen can cause fish deaths and lead to an imbalance in the different types of wildlife that live at the lake. In addition to the work by the Clean Water campaign, students of Drs. Dan Canfield and Chuck Cichra have been collecting water quality and fish population data as part of the Introduction to Fisheries Science (FAS 4305C) and Fish and Limnology (FAS 6932) courses for over 30 years. In lectures and hands-on field work, students learn how to collect and interpret water quality readings and how to estimate fish population structure and size. One of the lessons these students learned when the course was first offered is that an aesthetically-pleasing lake is not always the best lake for fish. In previous years when the lake was bright green—before the treated effluent was re-routed—Dr. Canfield and Dr. Cichra’s students were amazed at the large size of bass and other sports fish they caught. “They had been taught for years that a green lake was a dead lake. It didn’t take them long to realize that wasn’t the case for many of these fish species,” said Dr. Canfield. Over the years as the lake has become clearer, data collected by Dr. Canfield’s class indicate that fish populations have declined both in size and number, and there are also fewer ospreys than in years past. Some fish kills have occurred, but Dr. Canfield indicated that these were caused by severe low temperatures and invasive species such as tilapia. Dr. Canfield also stated that “Water quality has become very focused on issues of phosphorus and nitrogen, while ignoring other important issues like bacteria.” Fish living immediately at the discharge site previously had a high rate of infections and fish in the lake still experience these problems, which demonstrate the need for a water quality plan that also looks beyond chemical measurements alone. So what is the future of Lake Alice and other natural areas on campus? “The next phase is for the university to decide what steps to take to balance the dual roles of having an aesthetically-pleasing lake and an area appropriate for conservation goals,” said Clark. This means incorporating what we know about the watershed from the water quality data that the Clean Water campaign collected into the future goals of our university and identifying the roles it wants Lake Alice to continue to serve. What does this mean for the rest of us that don’t have a direct impact on the decisions made by the university? While we may not be able to reduce irrigation run-off or help larger fish come back to the lake, there is a lot that we as members of the Gator Nation can do to take ownership of the health and well-being of the waters on our campus. For more information on the Clean Water campaign, visit http://campuswaterquality.ifas.ufl.edu to learn about events and activities. You can also become a part of UF’s wetlands club and participate in volunteer clean-up efforts around campus and in the Gainesville area. To learn first-hand about lakes, fisheries, and water quality issues, sign up for Dr. Canfield’s and Dr. Cichra’s course, taught each Spring and open to any junior or senior-level students with an interest in the subject. Our lake has undergone numerous transformations during the changes in water inputs and usage over the years, and the lake will likely not remain in its current state forever. The future of the water bodies on campus hinges on finding the correct balance between nature, administration, and the future expansion of our university. And while you may not be able to have a direct impact on decisions made by our university, you can do your part to help protect these important natural areas by becoming aware of the issues and history of our lake and becoming active in clean-up or educational efforts.

Every Monday and Thursday night, I take a 15 minute train ride on the Northern Line from Liverpool Central for my biweekly tae kwon do lessons. The classes vary throughout the week: sometimes we focus on technique, sometimes we focus on strength and endurance exercises, and some weeks we do so much kicking and sparring that I can barely manage the walk back to the train station. Last week we had our last two lessons before a summer break, starting with a seemingly relaxed warm-up that led into an intense 30 minute sparring session.

During our sparring prelude, someone asked about a former class attendee who hadn’t been around for a while. Our black belt instructor Paul said that he didn’t think the student in question would ever return, and wasn’t too surprised about it, commenting that the current number of students who had taken his class versus those who had completed their black belt was similar to what he had seen at other schools, including when he earned his black belt. The black belt ‘graduation’ rate according to Paul is around 1 in 35, so of 35 students that start tae kwon do training, only one will actually earn a black belt. Call it tae kwon do attrition or just the fact that not everyone’s cut out for the sport, but it’s no surprise that not everyone makes it to black belt stage. It’s a tough sport, as my legs can attest to after our final lesson of the summer last Thursday. But Paul’s comment also brought to mind thoughts of the parallels between training in martial arts and going for a PhD and career in research. The completion rates are a quite a bit higher for those going for a PhD (50-60% in the US and closer to 70% if you’re here in the UK), but the processes have a lot of overlap. It’s not that people going for a PhD or black belt who don’t finish are lacking in intelligence or athleticism, it’s that both processes require more than you expect at first glance. To succeed at both, you can’t just be intelligent or be physically fit: it takes additional dimensions of mental strength in order to succeed. After writing two previous posts that focused on the connections between scientific research and tae kwon do, namely in learning how to fail and the balance between rubber and steel, I was inspired to revisit the topic and delve more deeply into the parallels between these two seemingly different activities and to focus on the aspects of both that might not be as readily apparent as the kicks and punches of tae kwon do and the papers and grants of a life as a career researcher. Both require you to humble yourself. Regardless of how flexible, strong, or fast you are, everyone in tae kwon do starts with a white belt. The color white symbolizes a person having purity due to their lack of knowledge of the martial art, and as you progress through the colored belts towards black you gain knowledge of new techniques as well as some much-needed control of your abilities. As you go from white belt to yellow belt to green belt, you’ll feel pretty confident. You’ll feel like you can take on anyone. But as you progress further and further, inching your way towards black belt status, you soon come to recognize how little you actually know and how much of an expert you are not. There is always a move whose execution can be further perfected, a stance that can be stronger or more elegant, and regardless of what level you’re at there will be someone in your class who’s above you in some way. Training to become a scientist is very much the same: we start off in undergrad learning so much all at once, progressing in our classes and lessons, maybe even getting a bit of lab work under our belt. But at some point we dive into the big pond of scientific research, where we find that the world is so much bigger and that what we know is so much smaller than what we thought. We gain knowledge through school and in our research, but part of learning how to be a scientist comes from recognizing how little we know and what we can do to get to the next step. …but both also require you to have a thick skin. Feeling like you don’t know very much is a humbling experience, but it’s also one that you have to know how to counter with confidence. In both martial arts and research, you have to balance the humbleness of recognizing your place in the world with the confidence of knowing where you stand. It’s easy to let feeling like you don’t know anything or aren’t good at something turn into you thinking that your lack of knowledge or skills will set you back permanently. Those who find success in both research and marital arts are able to walk this careful balance between humility and confidence, able to recognize where they can improve but to stand firm in the place that they are strong. Both require good senseis. A mentor or coach is crucial for success in both martial arts and in doing a PhD because both of these processes are not easy. It’s not as simple as just progressing from white belt to black belt or from undergrad to professor: you need time and a structured environment for reflection, assessment, and a critical eye to see the flaws and strengths that you can’t. And even though both endeavors are seemingly independent activities in that it’s your belt and your research, you still need a good mentor to show you the way and to encourage you to work and learn from others in the process. Both will help you find confidence but won’t automatically give it to you. I’ve heard a lot of parents say that they want their kids to get into martial arts because it’s an activity that builds confidence. But as someone who started white belt training as a 14 year-old shy kid who grew up to be red tag and slightly more outgoing and gregarious 28 year-old, it’s not just the sport that makes you who you are. Confidence is one of those personality traits that function best when they come from within. I greatly enjoyed tae kwon do as a kid, but found that I find the sport more enjoyable and more relaxing now that I’m more confident in myself than I was back in high school. Both martial arts and science are great at building up the confidence in those that already have it, but you can’t start from nothing. If you’re lacking in self-confidence and then fail at something, you won’t get that boost of additional confidence you’re looking for and will find you less likely to try again, whether it’s a new sparring move or a complicated experiment. A good sensei will work on developing your confidence from within, finding where you’re most comfortable, and figuring out how to help you shine without having to rely on your results to give you the boost you need. The positive side is that if your own confidence has been boosted, you’ll feel good enough to try new things, to explore new ideas, and you won’t be as afraid to fail the next time around. Both require you to take a lot of hits before you learn how to fight back. I spent 8 years on hiatus from tae kwon do and I came back into the sport only as a post-doc during the past two of years. Some of my muscle memories for techniques and forms stayed in place, and I’m also in better physical strength than when I started 14 years ago. But it didn’t mean that I was ready to jump back into being a black belt, since there were still quite a few places where my lack of practice and instincts were apparent. As an example, in free sparring I’ve become much better at attacking than when I first started, in conjunction with the downside that I’m still getting hit quite a lot since I didn’t build up my defenses to the same level as my attacks. In science, there are numerous occasions when your strengths and instincts will be tested. Hard-line questions and critiques by your graduate committee, advisor, conference audience, and lab mates, and you’ll essentially be dealing with an onslaught right from the get-go. It can leave you reeling and hurt, as if you were in your own intense sparring session. But the thing I’ve learned about sparring is that even if you’re not perfect, the next time you fight you won’t get hit in the same place again. You learn (even if it has to be the hard way) what parts of your work are the weak points and what you can do to make the weak points stronger. A career in research isn’t about putting up a good fight 100% of the time or only retreating from others: it’s about knowing how to move forward but also to protect yourself and foster your ideas and work at the same time. Both can be used to let your strengths shine, whatever they might be. One of my favorite things about martial arts is that it’s a sport that can be done by more than one type of person. Regardless of your body type, natural strength/flexibility, height, or weight, you can be good at martial arts and can get your black belt. In my class I’ve met other students who are extremely fast, flexible, strong, or just plain fearless. I’ve seen people who are good at sparring, who excel at forms and technique, or who are just brave enough to try anything crazy-and to me, they are all amazing martial artists. I also love that in science, despite being thought of as a place where only geniuses and nerds can succeed, you meet so many kinds of people. Some are great writers, others give amazing conference presentations, and others are wonderful group leaders or efficient lab managers. You don’t have to fit a cookie cutter ideal of what a scientist is in order to be a good one. In science as in the martial arts, what’s important is fostering the strengths you have and recognizing what you need to work on and how you can better complement your skillset. In both martial arts and in research, I somehow ended up becoming something of a jack-of-all-trades. I enjoy all aspects of both martial arts (forms, technique, flexibility, strength, sparring, and ferocity) and science (lab work, data analysis, reading, writing, meetings, and tweeting) without really excelling at one aspect or another. Sometimes I feel like I’m less skilled than others who have a more obvious specialty, whether it’s while sparring with someone who is faster than I am or when asking my lab mates to help me troubleshoot R code. But thanks to my own confidence in both parts of my life, I’ve been able to recognize that that’s just who I am and I value the way I work and live, even on the days when I come home exhausted from an intense work-out or a long day in labs. I’m thankful for the life lessons provided by both of my primary activities, and in the tough times I look ahead to days when my bruises are few and my manuscripts are many!

I tend to get in trouble by our lab safety officer once every two weeks for not wearing a lab coat. I always wear one when working with some dangerous or caustic chemicals, but most of my time spent in a molecular biology lab isn’t hazardous to my health. The main reason that I don’t like to wear a lab coat when it’s not necessary is maybe an unusual one: I don’t want to look like a scientist. Even as a researcher who’s been working in a lab for the past 8 years, I don’t want to fit the stereotype of what a scientist looks like or acts like. But what is the stereotype of a scientist? How do they look and, most importantly, how do they act?

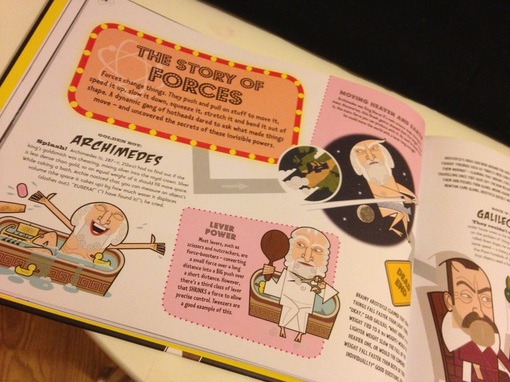

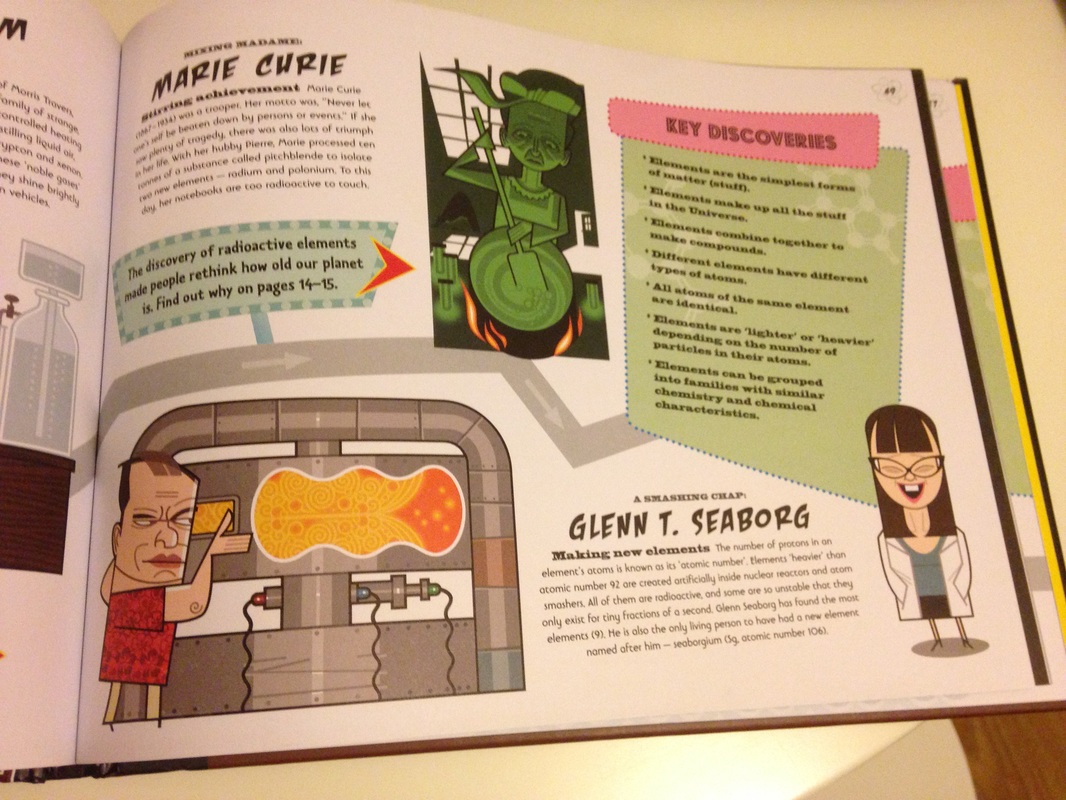

During this summer of lab work, writing, and tweeting, I’ve also been thinking about the ‘big gap’ in science, the gap between what the public thinks of what we do versus our actual research. PhD comics author Jorge Cham does a great job talking about this gap in his TEDxUCLA talk. Cham gives an example of good science communication in a collaborative project to develop a cartoon and video about the Higgs Boson. He makes note that this approach to sharing science took a lot of initiative from the scientists themselves, and it didn’t follow the traditional way of how science is shared with the broader community. Cham also comments on how shows like Big Bang theory portray researchers as eccentric and socially inept, which paints an inaccurate picture of scientists and can make the job seem unattractive to young students who don’t consider themselves geniuses or ‘nerds.’ While I do enjoy Sheldon’s banter on Big Bang Theory (because we all know someone like Sheldon in our group of colleagues or friends), I wonder if there’s a better way to talk about who scientists are and what they do. These wonderings led me to buy the children’s book, Rebel scientists, last week from Amazon. Rebels play a prominent role in modern-day storytelling: whether it’s Star Wars, Hunger Games, Braveheart, the Matrix, or the French and American revolutions, we all love to cheer for the rebels and the underdogs, be they real or fictional. But can scientists really be a part of this adjective? Dan Green’s book was one of the winners of the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize for this year. The illustrations, done by David Lyttleton, are a real treat for the eyes and help to focus the storytelling on the scientists themselves and how their work fits into the picture of our understanding of the universe. The book starts off with the timely question of “What is this thing called science?” and Dan describes it in four parts: curiosity, disagreement, discovery, and a long journey. Scientists are the ones who are curious about how the world around them works. They go against the consensus and the status quo when need be. They know that the world has a lot of mysteries that lie ahead and are driven by asking the why and how of everything and anything. Each science subject is presented as a separate chapter called “The story of ____”, with topics including the solar system, the atom, light, the elements, and genetics. Within each story, Dan starts with the early earliest thinkers and their ideas about how the world works, following through to what we know and are working on in science today. The book depicts the scientific exploration using a diagram of a road which connects discoveries together, while also provides road signs that the reader can follow to link to relevant material in other fields. The road even has the occasional dead end at an explanation of an idea that didn’t quite pan out. While the book is meant for a slightly older reader, probably for students ages 10-14, I’m amazed with the breadth of topics that are covered-and even complex subjects like quantum physics that I even had to re-read a couple of times to get the gist of the story. Below you can find a couple photos from inside the pages so you can get a sense of how the story of science and scientists are told by Dan:

I like how the book describes the Galileo’s and Einstein’s of our world: instead of calling them all geniuses or describing them as hyper-intelligent, the famous thinkers of our world are described with a wider breadth of words. ‘Rock star’, ‘radical’, rabble-rousers’, ‘sharp suited’, and ‘mavericks’ are just a few of the adjectives used. There are stories of disagreements between the biggest minds in science and how they came to a consensus about how the world works. There are stories of researchers going against the grain to pursue their ideas and delve into the mysteries that the rest of the world wasn’t able to see. At the end of the book, you can feel like the moniker of a ‘rebel scientist’ isn’t that far from the truth.

Reading this book also got me thinking about the other things that scientists do and that they are that might not come up at first though, since the thought of a 'rebel scientist' also wasn't the first to spring to mind. So what, exactly, do scientists do? We get things wrong, and that’s OK. There was more than one road in the Rebel Scientists book that lead to a dead end. But it wasn’t mentioned as a bad thing or that the person who thought the idea was stupid, it’s just a part of the process of science. Modern day science is rife with failures, experiments that go wrong, and ideas that lead to dead ends. It doesn’t mean we’re doing our job wrong, but it may not come to mind to non-scientists that as scientists we might not actually know everything. As Jorge Cham said in his talk, 95% of what makes up the universe is unknown…our world is complex and we have a lot more work to do! We are diverse, but we can do better going forward. A majority of scientists that feature prominently in history are men from Europe and North America. Some women do make an appearance, as well as a few Arabian scientists, but historically the science community hasn’t been diverse. The modern landscape is more inclusive, but we can still do better. What steps can we take in the future to ensure that everyone has the chance to contribute to the scientific community? Our job is to challenge the status quo. While scientists might be interpreted as know-it-alls or geniuses who can memorize textbooks and equations, a scientist cannot succeed simply by rout memorization of existing knowledge. Scientists have to be rebels that go against the grain, because that’s how we learn, uncover, and discover. To succeed in science, you have to do the unexpected, and being an elite know-it-all will only hold you back from uncovering the secrets that the universe has hidden from plain view. As Einstein said (and you can read more about him on Page 72 of Rebel Scientists), “Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” We do our best when we work as a team and not against each other. There are a lot of dramatic rivals highlighted in Rebel Scientists, and those of us that work in a lab will know of a few other ‘rivals’ of our advisors, collaborators, and colleagues. But what I like about this book is how it highlights the ideas that were put forth not by competing groups but by scientists working together to put the pieces of a puzzle into a single, clear picture. It’s tempting to want to blaze our own trail to fame and glory, so this book is a nice reminder that if the goal is the search for truth and understanding about the universe, working alongside others is better than working in opposition. Our world is an exciting, terrifying, and unimaginably big place. Figuring out how and why it works the way it does takes brave, enthusiastic, and rebellious minds. If people can rally behind the rebels of the science world as they do for Luke Skywalker or Katniss Everdeen, then Rebel Science will have succeeded in its mission. I hope to see more authors like Dan Green who are working to change the story of science and scientists into something more accurate and more engaging. May the force be with us and the odds ever in our favor!

“When it rains it pours” is not just the motto for Morton’s salt, it’s also a good analogy for a researcher’s to do list. More often than not, it feels like deadlines all come at once. But working in an academic research environment doesn’t have the same kind of pressures that a traditional office setting does. Researchers have an immense pressure to get things done, but when there’s no project deadline or a looming submission deadline, there really isn’t a solid reason that something has to get done at that moment in time. Deadlines are the way that most companies stay working on schedule, but in the world of academic research, how do we get things done?

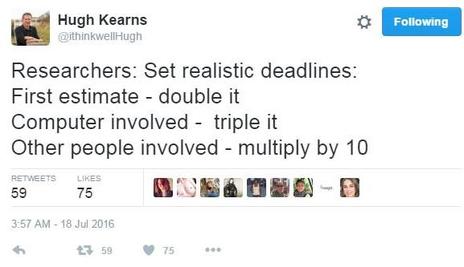

Let’s start with a typical example of research output: a manuscript. Unless you’re sending an article to be part of a special issue or when you’re doing a resubmission, you probably won’t have a hard-and-fast-deadline for submitting a manuscript: you can send in a paper any day, be it next week, next month, or next year. Academia then becomes this blend of feeling like we need to get something done but accompanied by a deadline that’s more fluid, depending on when you feel like you need to get it done, or when your boss or PI wants you to finish it. But even amidst the pressures your PI might put you under, the fact remains that you can still submit your manuscript at any given time. And while you might have a PI that gives some hard deadlines on projects, papers, or analyses such as “Have this done by your next committee meeting”, it may not come in the form of “Have this done by midnight on October 3rd,” as you would have had for classroom assignments and homework. And that’s not the only place that academic deadlines show their more fluid side. I found myself laughing out loud by this recent tweet by @ithinkwellHugh: If you’re still at the stage in your career where you’re working more independently, the last point might seem a bit daunting. “Ten times? Really? Surely that’s an exaggeration.” But anyone that’s worked on a large group project before knows that this multiplier factor is spot-on. Collaborating with other researchers on big group projects, projects that might not have a solid deliverable deadline akin to submitting a manuscript, means that the pace of the work is inevitably much, much slower. This initially might be a welcome pace, especially if this work not crucial to your out research output, but after weeks or months of inactivity from all parties due to a lack of central oversight, someone will realize that something needs to get done and it needs to be finished right now. And depending on your specific role in the project, the bulk of this last-minute, needs-to-be-done work could easily end up falling on you. The way that academic research and collaborations work is not likely to change anytime soon, but it doesn’t mean that all your work has to pour down on you all at once. You can develop a working strategy that helps you set yourself apart by learning how to become your own boss and track your own productivity. As independent researchers in the making, learning how to be in charge of setting your own deadlines and keeping other collaborators and colleagues working within a deadline-less world is an essential task. Here are a few ways to work towards a more productive working schedule even amidst a deadline-less working environment: Figure out your tendency. We reviewed Gretchen Rubin’s four tendencies in a previous post, and if you haven’t already checked out the quiz and read about the typologies, be sure to give her books and website a look. Especially if you struggle with stress at work or with staying on task, Rubin’s approaches for developing productive habits and working styles that align with each tendency are a great starting point. It’s much easier to figure out what strategies will and won’t for you in a research environment if you can better understand how you work and how you relate to expectations and deadlines, and you can use these approaches to make sure you don’t over-work yourself or under-deliver on your research outputs. Be realistic. For each of your big-picture, major tasks that you need to finish for your project, think in detail about all the components. If it’s lab work, how much prep time will you need for a single experiment? If you’ve done something similar before or are scaling up a smaller part of your work, how long exactly did it take and was there any troubleshooting involved? If it’s computer-based, how much of the work can be streamlined and how much time will it take for programming, formatting data, etc? It’s easy in research to trivialize tasks, especially ones we do on a regular basis, only to realize while doing something on a larger scale or on a short deadline how long it actually takes to double the number of replicates or to run code on a dataset that’s ten times the size. As with Hugh’s tweeted recommendations, give yourself some breathing room, especially if it’s something you never did before. Once you have an estimate that will give yourself a little bit of breathing room, double the time, since a dropped test tube or a computer freezing up can still set you back. Setting yourself up for success can be linked in part to knowing what’s feasible in a given amount of time, which can help reduce your stress levels by knowing what needs to get done but at the same time taking a breather in knowing that it will get done. Make daily and weekly goals. It’s easy to get stressed while thinking solely in the long-term months and years of all the work you have to do. Instead, put more of your focus on what you need to do that day and that week, and keep your big picture to-do’s in you peripheral vision. Given your realistic timelines, what should you work on today? What lab or computer work can you fit in together to give yourself a break from one or the other while still staying productive? If you keep your appointments and meetings in an online calendar, also include a place where you can list your daily to do’s, and check things off as you finish them. If you still enjoy keeping an analog version of a day planner and to do lists, write down what you need to get done that day and that week and check them off when each one is done. Doing this also helps you feel like you achieved something, especially if there may not be a ‘real’ deadline involved with the daily tasks or if the big picture to do, like publishing a paper, is a bit further ahead in the future. On a weekly level, have a few bigger picture goals in mind that are distinct from your day-to-day tasks and that can help you further your longer-term goals. Are you working on a manuscript and need to sort out your outlines or figures? Do you want to get in touch with a potential collaborator about an idea you have but always seem to forget to do it? Have these written off to the side of your daily to-do’s, and when you find yourself with 20-30 minutes to kill, take a look at your weekly goals and see what can be done in that period of time. You may not get everything done that you set out to do for your weekly goals, but keeping some bigger picture to do’s in your periphery can help you from being blindsided by big tasks like submitting a paper or writing a grant proposal. Recognize when you’re not being productive and step back. There is such a thing as trying too hard: sometimes when trying to get or stay motivated or focused, we just end up worn out and opening yet another tab on the internet (or, nowadays, checking our phone to see if any pokémon showed up nearby). Academic guilt has a way of making you feel like you should work all the time, but this is never a good strategy. Focus on getting your daily and weekly to do’s done, and if you find that you get to the end of one task and are not quite ready to start another, take a walk around the lab or make a coffee and give yourself time to digest before jumping in feet first to the next thing on your list. In big projects, make tasks and objectives clear. The first step in successful group work is being clear on who’s doing what. Make sure that the tasks and deliverables for the project are clearly delineated, and if something belongs to you then do your best to finish that part of the project on time. If things that you’re doing hinge on what people will do after you, keep them informed of your progress and any blocks you run into. If someone has given a deadline for a project, then treat it as such, even if there may not be a company or boss who’s breathing down your neck about it. Remember that even in research, your time is money, so take the time you need to complete a task for another project and allow the project to move forward instead of making it drag on. In group work, you may end up with someone who isn’t pulling their weight on their part of the work. It’s frustrating and will more often than not make you upset, especially if you’re in charge of the project. Instead of getting mad right away, ask them what you can help with and if they need an extension due to some issues on their side. If all else fails, be ready to take over the and consider this in the planning stages of the project by budgeting in some time for the possibility of having to do the work of someone else. Not everything has to be done in research, but there’s still a lot of things that should be done. In academia and in scientific research, you set yourself apart not by doing what you’re told but by doing something more. Bosses and deadlines will always be a factor in motivating us to finish a boring task or assignment, but for a successful career in research you’ll need to develop a strategy for working and figuring out how to inspire yourself to work when no one is looking. You can’t see everything as just a list of of things you have to do but should instead see a collection of ideas that are so great that they should be done. Research is a tough gig, but it doesn’t have to feel like your life is an endless stream of tasks and deadlines. Developing your motivation and time management skillset can keep you from being bogged down by deadlines (or a lack thereof) and can keep your work progressing on a regular basis instead of having everything fall on you at once. If you’re motivated to keep pursuing a career in research, find a way to let your work be moved by your passions instead of your have-to-do’s, and then even amidst the downpours you can find some comfort in knowing that you’re doing the best you can to make the world a better place. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed