|

Hello from the red rock valleys of the Mountain West! This week I took a break from posting to enjoy the scenery of home and to prepare for a busy week of short posts and tweets from the 36th annual Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry meeting next week. It will be a busy week following the science communication and outreach sessions and talking to other toxicologists about the SwS blog.

I'm also working on a survey which I'll keep a link for in the Contact section. I'd like to hear about your experience in research, what training programs you think would enhance your career, and how your expectations of life in science were met or not. Until Sunday, I've got a couple more days to enjoy the sun and rocks before a busy week of science and networking in the stylish Salt Lake City. Follow us on twitter for live updates during the conference on the #SETACSLC hashtag. For those of you heading to SETAC, see you soon! Playing nicely with others: When success in science hinges on more than just what you know10/21/2015

I think it’s safe to say that most of us have benefited from Jorge Cham’s PhD comic series even if our research and general productivity hasn’t. It’s easy to spend an afternoon scrolling through the comic archive and thinking Yep, been there, done that, seen that. His all-too-real depictions of situations strike a chord with many aspects of life working in a research laboratory. One of his recent comics resonated for me on two separate occasions. Originally posted on Sept 4th, I think I actually laughed out loud when I first saw this one:

I’ve seen far too many similar warnings posted in the lab, office, or shared kitchen, reminding us all that equipment belongs to one person and one person ONLY, or reminders that ‘your mother doesn’t work here, so clean up after yourself’. I’ve received a fair amount of scorn from lab managers and senior grad students or post-docs for using a piece of equipment without signing the log book about the 2 minutes I spend on the machine. I have borne witness to a wide array of emails on department and even college-wide email lists chastising someone for a minor infraction or something that could have been handled more maturely and directly (instead of involving the entire department). While Jorge Cham might lead us to believe in his comic that grad school isn’t kindergarden anymore, sometimes I feel like we’re back in elementary school all over again, but this time with the mantra of ‘sharing is good’ replaced by messages on snarky post-it notes indicating that if someone doesn’t clean up their mess they’ll be promptly sent to the 3rd circle of hell.

While it’s easy to laugh about situations like this, these attitudes in academia, and in scientific research as a whole, can hold us back from making progress in our work. I was reminded of this comic a second time last week when I found this article “How the modern work place has become more like preschool”. The article is not comic material but instead discusses the reasons for the increase in the number of jobs requiring interpersonal skills. While the loss of many ‘unskilled’ jobs may not be of concern to someone holding or working toward a PhD, in today’s competitive workforce there are WAY more PhDs than ever before. The traditional place of employment, academia, can’t make homes for all of us, and those that are trying to get into any sort of permanent position will be competing against a long list of other applicants, some with more publications, more grants, or more relevant experience. Interpersonal skills and how you work with others in a team setting can make the difference in you landing your dream job versus you landing just any job. The Nobel-prize winning economist James Heckman wrote a paper on the relationship between cognitive skills (e.g., intelligence as measured by aptitude tests) and non-cognitive skills (e.g., motivation, perseverance, self-control, etc.) and how these two factors correlated to endpoints related to success in life: getting a 4-year degree, how much money you make, etc. While there are quite a few conclusions that can be drawn from the results, depicted as surface plots over the two-dimensions of cognitive and non-cognitive skills (scroll to the end of the paper), the quick take-home message is that it takes more than just being smart to succeed. It’s a combination of how smart you are as well as how well you make it through life’s challenges and how you interact with teachers and peers. There is a strong need in today’s workforce, and in science especially, for people who can empathize, see others emotions, and respond to them appropriately. The New York Times article goes on to describe the reason for its title: “Children move from art projects to science experiments to the playground in small groups, and their most important skills are sharing and negotiating with others. But that soon ends, replaced by lecture-style teaching of hard skills, with less peer interaction. Work, meanwhile, has become more like preschool.” This is an all-too-true situation for those of us in the scientific fields: we spend our time in high school and undergrad gaining in-depth knowledge on a topic before we graduate. Then for those of us that decide to continue our studies, the world suddenly changes: the bulk of our time is now spent in lab meetings presenting our research, learning a new protocol from a lab mate, collecting data with a collaborator, or revising papers with our advisor. While there is always a part of your research where you will work independently, the collaborative atmosphere is much more prevalent after your undergraduate studies. It’s here that the natural sciences such as biology and chemistry can learn a lot from engineering programs. A bachelor’s degree in engineering is designed with the knowledge that after graduation most engineers will work in teams on large projects. As a student, group projects may seem tedious, but they provide experience with necessary teamwork skills such as how to divide tasks based on the members’ skills and knowledge. As such, students who will end up as professional scientists could also benefit from team projects. Just like how trends in the general workforce are leaning away from hiring people that can only do manual labor tasks, scientists need to hone their teamwork and collaborative skills in order to set themselves apart from the rest of the crowd. Another section of the NYT article describes a situation that many of us have likely faced already: “Say two workers are publishing a research paper. If one excels at data analysis and the other at writing, they would be more productive and create a better product if they collaborated. But if they lack interpersonal skills, the cost of working together might be too high to make the partnership productive.” This is an example of something that happens all too often in academia. If people know that you’re a genius at what you do but know that you can’t be bothered to sit in a room with other people and work together on a problem, who do you think they’re going to hire for the project manager position or ask to help write a grant with them? As stated in the NYT article, “Cooperation, empathy and flexibility have become increasingly vital in modern-day work.” Likewise, science has become a world of collaborations: large-scale international grants, multiple PIs with teams of graduate students and post-docs, data that requires expertise from several areas of knowledge, or a complex physical infrastructure (such as the particle accelerator at CERN). Science does not work in a vacuum, especially in this day and age where so many of the questions that remain to be answered are pressing and complex. As professional scientists we need to learn how to play nicely with the rest of the class. As you build a network of collaborators, you’ll find that this will be much easier if you earn people’s respect for who you are both as a scientist and as a person. While non-cognitive skills and ‘politeness’ lessons may not have been covered since your time in kindergarten, you will spend your entire life outside the classroom being evaluated on this skillset. It’s your responsibility to be aware of how you work with others and your strengths and weaknesses outside of your basic foundation of knowledge. To give some guidance, I’ve compiled a few things to keep in mind in order to help you play well with others. - Visualize any collaborative venture as a team effort. When you work in a group, look at people’s skills and expertise and think about what components each member can contribute. Keep in mind who will be timely with their efforts, who will need additional support, and who can be trusted to finish their contribution independently. - Foster an environment for sharing your research. Take ownership of your research but don’t keep it to yourself. Talk about ideas with your lab mates, your PI, as well as researchers completely outside of your research group. Seek out new perspectives on your work even if it’s not a formal collaboration by sharing insights and data with your peers and people outside your lab. - Your mother may not work in your lab, but pretend that she does. Moms tend to give good insights on how society expects us to behave. Even if you’ve been out of her house for a while, keep her recommendations in the back of your mind when it comes to how you conduct yourself (and the next three bullets are certainly mom-approved!). - Be nice to everyone. No matter what level of lab/office hierarchy, be they technicians, office staff, or administrative personnel, being friendly and cordial to people even when you don’t have to be will make your day-to-day life easier. It’s not just about being nice to your PI but to the people who will bring you deliveries, get your paperwork sorted so you can get paid, and who may or may not look past office deadlines in order to help you out. - Think before you speak, ESPECIALLY in emails. There will be a lot of tricky situations you’ll be faced with: scientists that don’t respond to emails, challenging your findings, or demanding more than was agreed on in a grant proposal. You don’t need to be snarky or defensive, and most issues can be managed politely without the need for overly strong wording. Remember that your emails can very easily get forwarded to a department head or saved in someone’s inbox, so use some thought before you send them! - Pay no mind to jerks. You will run into people that you won’t like, ones who won’t work well as a team or who will continually seem to poke you with a stick. Don’t worry about them, and as your teacher or mom said: mind your own business, at least when it comes to letting people interfere with your work and your mood. Do your best to try to establish a professional relationship as needed, and if that person is truly caustic then find other teammates to work more with, and be comforted by the fact that they’ll likely run into later issues with finding collaborators and colleagues in their own careers. Academia can feel like a ‘don’t touch this it’s mine’ kind of world, where the good guys just can’t win. There will inevitably be people that make messes or that won’t be nice to you. How can you set yourself apart from this preschool mentality? By setting an example through your courtesy and kindness. Focus on establishing a positive attitude for teamwork and collaboration, and work on the transition from a mindset of ‘don’t touch this it’s mine’ to ‘it’s nice to make friends!’ Your research now as well as your career in the future will be better off for it!

The Lakes District offers some of the UK’s best scenery and is a popular destination for weekends and summer retreats. Before I moved to England for my post-doc, a friend of mine took me for a day trip to the region during my visit to Durham in 2013. It was a spectacular mid-August day, with not a drop of rain and just a touch of wind. I remember looking down into the valley from the summit and feeling like it was a scene taken straight from The Hobbit. Another trip to the area a year later recalled a similar mood: with gorgeous greens contrasting stony heights and shimmering lakes, who wouldn’t want to spend a weekend wandering about this amazing landscape?

But as much as I and the rest of England love the Lakes District, it has a notable and well-earned reputation for crappy weather. Storms can come from nowhere and leave you wet, cold, and uncomfortable, and summits that leave you exhausted even after only a 1km ascent. After the two previous sun-filled summer trips, my husband and I went by train to hike around Lake Windermere in March of this year. While not expecting the lavishly sunny warmth of our last visit, the ever-present fog prevented any sort of view that day. This past July we made a full weekend trip to try to summit the tallest peak, Scaffel Pike, only to finish summitless due to disorienting fog before becoming drenched to the bone by cold driving rain, shivering in the car ride back to the hostel and spending a good 20 minutes in a hot shower trying to warm up again.

I thought back on these previous Lakes District jaunts this last weekend, as we headed to take on Scaffel Pike a second time. While the leaves hadn’t changed to their autumn colors like we had hoped, we were rewarded with a fantastic weekend at Wast Water Lake: no rain, small crowds, and a chance to breathe fresh air and stretch our city legs. At the same time, I couldn’t help but reflect on previous hikes, as well as my own ongoing ‘journey’ through a career in science. While I’ve already drawn parallels between getting a black belt and getting a PhD, I can also see a parallel between the joys and challenges of the Great Outdoors with those of becoming a professional scientist. Both offer challenges, opportunities, and rewards, and the parallels between the two can give us insight and perspective on how we should approach the hard times we inevitably encounter while navigating our way to a rewarding career. Be prepared and ready to adapt. A day on the peaks can be glorious or it can be dreadful, sometimes back and forth in the very same day, so be ready for hot, cold, wet, and/or windy weather. Carry a good map, plenty of water, and some extra socks, although after your first hike or two you’ll probably learn the hard way what you really needed in your bag. At the start of graduate school, I thought my undergraduate coursework in biology and chemistry would be all I needed to start research, but I quickly found out this preparation wasn’t enough. So I got deeply familiar with the literature, learned to optimize assays before running important experiments, and reached out to advisers and professors when I got stuck. These are the things that kept me dry through rainy spells of my PhD project. Know when to take in the scenery and when to keep going. While the summit or the trail’s end might be the ultimate goal, knowing when to enjoy the moments before the ultimate goal, and when you need a break to help you get to that goal without being exhausted, will make the trip more rewarding. At the same time, there will be times when you can't make a break at every view point and moments when you need to push through a bit of discomfort or tiredness to get to another milestone along the trail or a more sheltered place before the rains head in. As with the previous post on rubber versus steel, the key is to maintain a trajectory for your ultimate goal while recognizing that if you just push for that goal without stopping you’ll miss so much along the way (and arrive at the end exhausted). Stay focused so you don’t trip, but don’t forget to look up now and then to see where you’re headed. Some parts of the trail will be easy, where you can look around at the sights along the way, oblivious to precisely where your feet land. Other times there will be boulders, steep drop-offs, or slippery rocks that you’ll need to watch closely as you walk. As a scientist, there will be crucial moments that require your full attention: a technically difficult experiment that you get one shot at, planning an annual sampling expedition for the two weeks of the year that you can get samples, or writing code that will take months to run before you get an answer. When these moments come, give your focus to them and think about each step you take, and what can go wrong at each point, in order to achieve success during that crucial moment. At the same time that staying focused on one step at a time is important, don’t forget to look up now and then and see where you’re heading to make sure it’s still in the right direction. It’s easy to think that because we’re still on a trail that we’re going the right way, but oftentimes we might find ourselves on a side path we never intended to be on if we are only looking one footfall ahead at a time. If you find yourself staring down at the same assay or experiment over and over again, take a look at the bigger picture and see if it’s still the right direction. Even if you thought that this was the right way, it might turn out that the data is trying to tell you otherwise, but you may need to look up from your pipettes in order to see it more clearly. The journey is better with friends. There are times when a solitary hike is a good thing, but more often it makes for a better time when you share the road with friends. You’re less likely to feel bitter in a downpour or to get mad at yourself for missing a turn if you’ve got good friends and colleagues who are on the same road with you. At the end of a long hike you’ll have someone to laugh with about the casual mishaps and to exchange stories with at the trail’s end pub, celebrating feats of strength and good views and commiserating with each other about the rainstorms and the sprained ankles. While you may be the only one wrapped up in your specific project, you likely have a lab or an office full of other students or researchers who are on the same journey as you. Share your joys and challenges and listen to theirs in return. Even if you’re working on completely different topics, you’ll often find a lot of intersections you can meet at or parallels between your separate journeys, whether it be rejected papers or terrible lab meetings. Keep these people close during your own journey, and let them remind you that you’re not out there in the wildnerness on your own. There will be ups and downs. Some hikes you’ll do will be fantastic, sunny, and you won’t get lost or even tired out. Other hikes will absolutely suck, it will be rainy and windy and you won’t even get to the summit, or you’ll get there and there will be nothing to see but a giant cloud. Likewise, some experiments will work the first time around, you’ll have beautiful results for publication, but other experiments won’t work at all, or you’ll get results that confound everything you did already and you’ll sit there scratching your head about what to do next. The key is to persevere through the rougher times, knowing that if you keep on going you can reach another valley where the sun is shining and the p-values are significant. Part of the destination is the journey. As many millions of ways as it’s been said before, it’s not just about where you end up but how you get there. If you get to the end exhausted and not having seen what was along the way, was it as worthwhile as it could have been? If you went straight to your destination without facing challenges or enjoying the sunshine, did you learn as much as you could have? You learn as much about the end result along the journey itself as much as you do just from arriving at the end. The gear you really needed and what was superfluous, what trails led to something good and which ones got you nowhere, and finding the balance between the moments of intense focus and moments when you just enjoyed the walk. When you actually get there, you’ll recognize the importance of every step you took more so than when you’re on your way. I had this stark realization at the end of my PhD defense. I gave an hour-long seminar about 4 years of work, then I was asked a few questions about future experiments and experimental design for maybe 45 minutes by my graduate committee. Then I was done, and in a matter of a few minutes deliberation and signing paperwork, I had a PhD. My first thought wasn’t exuberance, it was … Really? That was it? And now I’m a PhD? I felt a bit cheated, like I hadn’t done enough to warrant the end result of becoming a doctor. Soon enough you realize that it wasn’t that hour-long seminar and a few questions that got you the PhD but rather the 4 years of work that led up to it. The years of staying focused on answering questions while knowing when to take a side path and explore something else, of pushing through the rainy days while enjoying the sunshine when it came, and also writing a really long, probably rather boring 182-page word document. But that’s a topic for a future blog post. One of the things I love most about hiking is that it’s one of the things that truly anyone can do. You’ll see everyone on the trail: from the power couple with matching Gore Tex jackets, a laminated topographical map, and a portable oven for making steak and ale pies on the summit, to the stag party guys in tennis shoes and jeans. While everyone comes to the mountain with their own set of gear and motivations, we all get up the mountain the same way: one step at a time. With the right mindset, navigating to a rewarding career (or just getting through your PhD) is something that everyone can do by taking it one step at a time, by being prepared, and by learning from the journey as much as working towards getting to the destination.

“Network, network, network!” Networking is often touted as the most important thing that graduate students and young researchers should do, even early in their careers. While it’s easy for people to say over and over again how important it is and to generally understand its importance for professional development, what’s not as clear is how networking in scientific research actually works, and how you should go about networking effectively.

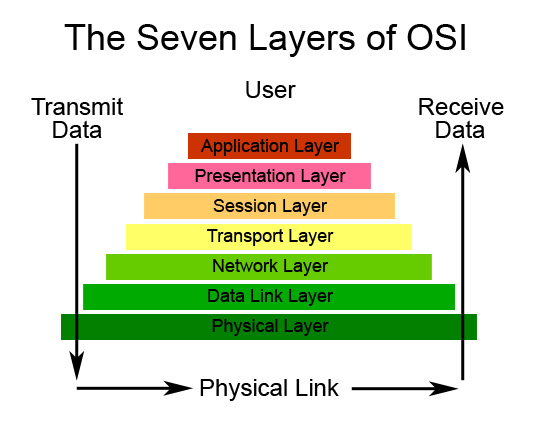

How exactly do I network? is a pressing question for students putting together the final touches on their dissertation and for post-docs and entry-level researchers who are running short of days on their contract. The elusive nature of networking can become readily apparent while attending a conference at during one of these crucial times, seeking out potential employers and setting yourself up for the next stage of your career while navigating through the busy crowds at poster socials. While some people seem to be natural at attracting collaborators and colleagues, for other it’s not as easy. For most of us, collaborators and potential employers won’t just appear from thin air, and networking is not always something that comes naturally, especially for those of us that prefer to keep to ourselves or who feel more out of place when interacting with groups of people (e.g. introverts, myself included!). Before we think further on how to network, we should first think about what networking is. Instead of rushing off to Webster, though, let’s turn to something that’s been pretty successful with its networking, by definition: the Internet. In addition to being many a source of most of the information we consume each day, with an array of activities ranging from productivity to procrastination, the Internet is also the perfect model for professional networking. The infrastructure used by telecommunication systems are designed with communication in mind, with the end goal of making purposeful connections between people and places. As nerdy as it may sound, we can actually use the infrastructure of Open Systems Interconnection models (OSI; more nerdy stuff here) to get a better picture of what networking is, and give us a road map of how we can actually go about doing this important yet somewhat nebulous professional task.

1. Physical layer

In the OSI model, a physical connection corresponds to the medium that allows the message to be transmitted, in this case electricity flowing through an Ethernet cable or the electromagnetic waves of wifi. For the wifi example, while there isn’t a solid physical connection, your computer has to be using the correct frequency and within range in order to get any signal. In professional networking, the physical connection is any sort of connection between you and another person, a connection that allows for mutual interaction and for being in their presence. It doesn’t have to be a physical or in-person interaction at first, the medium can be LinkedIn, a quick wave at a conference or workshop, or the fact that you have their email address in your contacts list since you were on the same email exchange about another project. The key is that this layer allows you to interact with the other person and to begin the next steps towards networking more fully. 2. Data link layer This layer relates to a reliable transmission of data between two nodes. It’s the same progression as with networking: you may have had a quick handshake at a conference dinner, but can you say you’ve really met them? For professional networking, this step means taking your connection further by reaching out to them with a bit more than just a ‘hello’ or a handshake. The key with this layer is to begin the process of active communication, with the goal of speaking the same ‘language’ and being on the same page. Whether it’s collaboration, a job, or career advice, this is the stage where you introduce yourself and start making a connection between yourself, your goals, and how the other person can transmit and receive back to you more reliably. Another key with this step is not expecting too much too early: don’t expect that a person you’ve never had an actual conversation with to hand you a post-doc. If you are interested in learning more about their group, present your goals and intentions but ask if you can talk or meet in person to learn more about their research, and for them to learn more about you, before you can expect much else more out of the networking relationship. 3. Network layer This is where things get more complicated in the OSI model: it becomes managing multiple nodes of information and routing information to and from the right places. After the initial contact, there will be a lot of back and forth about your problem and where to go forward. At this stage you probably won’t get a direct answer to your question or request, but may instead hear things like “Oh, so have you worked with Professor Smith?” “Did you read the paper by Smith et al 2014 on this topic?” The key here is to use your information and your connections to further expand your base network and increase your knowledge of potential contacts, focusing on suggestions and connections suggested by other colleagues. 4. Transport layer Once you’ve established a larger base network in step 3, you can have a more reliable movement of requests/data/information between yourself and your base network. You can then reach out to people and get more specific information on how to do what you are setting out to do and who you should be talking to. At this stage you’ll also have better luck with expanding your network further and for requesting more things like jobs or ongoing collaborations, because once people have established trust with you they are more likely to pass on your messages and requests, or forward along contact information to other colleagues, if they have some knowledge of you and your goals. The goal here is to establish a trusted connection between you and your contacts by demonstrating that you are a trustworthy, connected, and reliable person. This will enable you to take off in the next steps to grow these relationships even further. 5. Session layer With a set of trusted contacts in mind, you can now arrange a purposeful communication session: schedule a meeting on skype or at a conference to discuss research, draft a proposal for a grant, or ask about a research position. As in the OSI model, this will involve a lot of information exchange back and forth, so be ready to manage a lot of input coming in as well as meaning output being sent to them. With this step, you should be ready for a purposeful discussion that will lead you to your goal, and while the actual meeting doesn’t have to be 100% focused on the topic at hand, you should strive to achieve a result from this interaction by setting out with a goal and purpose for the meeting. 6. Presentation layer In OSI, this is where data gets translated, and for you and your contact this is where you both can showcase your ideas, ambitions, and intentions. Aim for clarity in the discussion: be sure that you know exactly what you’re getting out of the exchange, whether it be a collaboration or grant application or job, and that your continued interactions with your contact are also clear from this step forward. Have a plan for what you want to say, listen closely to your contact, and define the means in which you’ll both move forward together. 7. Application layer At this stage you’ve achieved high-level connectivity, and by doing so have achieved your original goal set out when you started your initial networking strategy. Whether this is a collaboration, a job, or a purposeful discussion about a paper with a new colleague, it’s the start of a continued deeper discussion between you and your new connection. The key with achieving your goal is to avoid skipping layers: you need to gain trust from connections beyond a quick handshake at a conference dinner, and you need to an appropriate venue and agreement on objectives and goals before you can pitch a grant proposal. Achieving the required trust, context, and clarity won’t get you a job or a paper 100% of the time, but it will certainly help. They key is to remember that you must build up a network of people who trust you and who understand you and what you’re doing, which is why it’s always recommended to do this earlier in your career rather than later. So now that we’ve covered the networking framework, I’ll share a few practical tips to get you started. These tips and tricks have helped me, a natural introvert who shies away from crowds and speaking out loud to omuch, to gain a wide network of colleagues and collaborators that I’ve met through conferences, advisory councils, and late-night scientific cocktails. One advantage of introverts is that we are good listeners, and as you’ll learn when you start talking to others about science is that people love to talk about their work and themselves. So the first piece of advice: let them talk! - Don’t be afraid to just say ‘hi’: Especially if you don’t know someone well, don’t feel like your first interaction has to be very formal or have some over-arching goal like a post-doc. If you have someone’s contact information, or bumped into each other at a workshop and didn’t have a chance to talk but you want to learn about the person more, don’t be afraid just to email them and say that you’re interested to learn more about what they do and who they are as a scientist. - Plan ahead: Especially if you’re meeting someone at a large conference, set a date and time to catch up with them, even if it’s just a casual discussion. It will help you make sure the meeting actually happens, as with conferences people tend to get busy and pulled each and every way to talks or meetings with colleagues. If you want to keep it more informal, go for a coffee or a walk instead of a sit-down meal or a relaxed after-conference drink, since it gives you more flexibility in terms of scheduling and is less of a time commitment for both of you. - Keep it casual but make sure you get to business when you need to: Especially when meeting someone more formally for the first time, don’t start the conversation too direct. Talk about the conference, the city, the latest loss/win of a local sports team etc., etc. Making connections is as much about getting someone to respect your work and your professional persona as much as it is having a person like you and feel comfortable around you. Break the ice as need be, then to avoid making the conversation too long-winded (especially for busy professionals) get straight down to the matter at hand in a clear yet un-rushed way. - Ask good questions: People like to talk and to be listened to, so obviously asking questions is the best way to get people excited about a topic. At the same time, you’ll get to learn more about them, how they think, what is exciting for them in terms of research, etc. Knowing someone better by hearing their side of the story, and letting that person share their story, can make your relationship one built on trust and understanding, not just mutual scientific interest. - Be ready: You may only get a short amount of time for your meeting, so be ready to say what you want and have a clear purpose or aim for your discussion. Obviously you shouldn’t bust out the notecards (might make it seem a bit too rehearsed), but prepare a couple of take-home sentences ready to fire off. This is especially good if you end up having to give a ‘elevator talk’, or telling a summary of what you do and what you want to do in a matter of 30 seconds or less. Being prepared will make your time count and your message stand out, even when the other person heads home after a busy week at the conference. -S tart now, no matter what stage you’re at: Building a network and establishing trust will take time, so starting early in your academic career will make it easier when you are actually looking for a job. Get involved with your favorite scientific society, or outreach groups in your university, and start talking to everyone and everyone about your research and your goals. You never know where you’ll find the connection that will lead you to your next job, or how a quick conversation about rugby and mass spectrometry can lead you to landing your dream job. Start now and cast a wide net for the best results! Apart from a lot of persistence and a dash of optimism, there is no perfect formula for networking. Some attempts will pan out, other connections will fade out quickly, and people you randomly talked to might surprise you by connecting you to someone with the golden ticket for your career. By thinking about how to build connections, using the Internet as an analogy, and approaching new colleagues and collaborators in an open, engaging, and well thought-out manner, you can build a network of trusted peers who will trust you back and help put you somewhere you’re aiming to be. So best of luck and happy networking, and for those of you heading to SETAC Salt Lake City, your first drink at the opening reception* is on me! *Drinks at the opening are usually free at SETAC (and hopefully still are, otherwise I’m soon to go broke!) |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed