'What did the Romans ever do for us?' Hadrian's wall (top), aqueducts in Segovia (bottom left), and the Coliseum in Rome (bottom right) 'What did the Romans ever do for us?' Hadrian's wall (top), aqueducts in Segovia (bottom left), and the Coliseum in Rome (bottom right)

One of the challenges of having a weekly blog is not knowing at what time or from where inspiration will come. Sometimes I have ideas in the queue for weeks at a time, other times I’m scrambling on a Tuesday night to come up with something for the next day. This week I’m leaning towards the latter approach, especially after returning from a long weekend/Easter holiday.

While I passed most of the weekend enjoying the sights, wine, and sunshine of central Spain, I realized that one of my favorite parts of travelling around Europe isn’t experiencing the modern-day cuisine and the culture, it’s the history and legacies that were left behind for us today that still inspire and motivate me. In particular, I love seeing the remnants of the Romans. On our first day trip from Madrid we traveled to the walled city of Segovia, which has an in-tact Roman aqueduct that was in use up until the 19th century. The aqueduct is imposing and impressive, nearly 100 feet tall (or 28.5 m, since this is a science blog after all) and stretches 15 km from the city walls. Not only is the original design impressive in its own right, the antiquity of the construction—which was started sometime near 50 AD—adds to its magnificence. We took the time to wander along the aqueduct trail to and from the city, and while admiring the structure I couldn’t help but think of the other impressive works that the Romans left behind. From the awe-inspiring views along Hadrian’s wall as it stretches across the Northern English countryside to the first moment when you see the grandeur of the Coliseum, you can’t help but be impressed by what was accomplished nearly two thousand years ago in a time with no computers, phones, cars, and a multitude of technologies that seem integral to our lives today. While I am certainly not an expert in Roman history, my trips to museums and my brief bits of reading about that period of history has given me an impression of how Rome functioned and thrived. As the saying goes, ‘Rome wasn’t built in a day’, and the breadth of the empire also wasn’t won overnight. It was only through years of wars and also diplomacy that the empire became what it was at its height, stretching from Turkey and Northern Africa all the way to England. But holding that much land in a time without telecommunication of any form required more than just military might. Part of what makes Rome stand out, and makes their monuments still stand today, is the recognition that infrastructure was the key to keeping things in order, in making people happy, and in building an empire that would last beyond one person’s lifetime. Say what you will of the finer details of how things were done in Rome, as it certainly had its fill of bad emperors, slave-based labor, and probable constant lead poisoning, but Rome as a whole was committed to keeping itself together. While other empires may have been held in tact by a single person, as with Alexander the Great whose empire fell apart at his death, Rome lasted and held itself strong for generations. Caesar Augustus commented on Alexander’s downfall in a quote by Plutarch: “He [Caesar Augustus] learned that Alexander, having completed nearly all his conquests by the time he was thirty-two years old, was at an utter loss to know what he should do during the rest of his life, whereat Augustus expressed his surprise that Alexander did not regard it as a greater task to set in order the empire which he had won than to win it.” So where am I going with this, apart from sharing my love of Roman history? One of the reasons that I’m always inspired by the Romans is the fact that they built things to last, and built things for the Empire and not just for themselves. While emperors certainly had nice places to live and probably led better lives than most people in Rome, some emperors like Hadrian (whose wall in England still stands to this day) spent a lot of his time as ruler travelling around and decreeing construction projects for public buildings and infrastructure that everyone could use. While self-indulgence is always a part of being an emperor, king, or leader, the best leaders recognize that giving something back to the people that work for you is better than rewarding yourself for your own leadership achievements. From the perspective of scientific research, Rome can provide us with a means by which to think about the type of work we do. We can make great achievements in knowledge and write the best papers ever, but if this work ends when we retire then what sort of legacy does it leave behind? If we focus only on conquering and not building an infrastructure, will things fall apart once we step away? Just as Rome wasn’t built in a day, great science also takes time to come to fruition, and the greatest scientific achievements were never done for self-indulgent purposes but instead were done while working towards a greater, longer-lasting good. As you think about your own research, envision a legacy and think of how your work can provide a framework of understanding for future researchers I mean, if the Romans could do all the things they did in the world that they lived in, how much could you achieve given the technology and the knowledge that we all have today?

The great philosopher Led Zeppelin has always has a way with words:

In the days of my youth, I was told what it means to do science, Now I've got a degree, I've tried to learn important facts the best I can. Memorized and synthesized and learned the entire Krebbs cycle too, [Chorus:] Good meetings, Bad meetings, we know you’ve had your share; When my attention span wanes after 3 hours, Do I really still need to care? As a career scientist in the modern era, you have numerous jobs besides being a scientist: you’re a project leader, teacher, motivator, finance manager, accountant, PR manager, public speaker, fundraiser, and personal secretary. In an ideal world, you could concentrate on doing your science, writing papers on your own at your own pace, and spending most of your day in your office or in the lab thinking about new ideas and bringing them to life. In reality, you have to manage your own tasks while working with others on large multi-organization projects, engage with collaborators to write new grant proposals, and be ready to work as a team to get something finished that would take you ages to do on your own. While we know the type of science needs to be done to make progress in our understanding of the universe, it’s not always clear how to do the necessary thing that will enable scientist to do this great work. One of the essentials is learning how to work in groups, and part of that is how to lead productive group work. Unfortunately we all know too well what a painful, unproductive meeting feels like: the project meetings where one person drones on endlessly, a conference call that was scheduled to last an hour but has already gone for an hour and a half with still three agenda items to go, or a club at your University that meets every month and always talk about the same thing with nothing getting done. It may seem more productive (and enjoyable) to avoid meetings altogether, but disengaging from work groups will put you at a huge disadvantage. Part of being a scientist means collaborating, and part of collaborating means you engage in group discussions. If you avoid them now but then end up in a project leadership position down the line in your career, will you know how to make an agenda? If you miss out on key discussions with a group you’re involved in, will you know how to make the group’s activities more impactful for both the group and your own career? If you skip out on face-to-face meetings on your project, will you know how to respond in a work setting when your boss turns to you in a group and asks ‘So, how does your project fit in with our 10-year plan?’ Learning how to be involved in group activities, as well as how to deal with groups that may not be going in an ideal direction, can set you up for success in your future career. Knowing how to lead a small group of people effectively and efficiently is a huge skill for any type of research position with leadership or management responsibilities. Honing the art of finishing a conference call on time, while still covering all the key discussion points and doling out action items, can help lead you to more papers and more grants. Regardless of what sector you end up working in or at what stage of your career you find yourself, learning how to manage and work in groups can bolster your own project’s productivity—setting you up for future success on a wider scale. What makes a group or meeting effective? - Having an overall goal. Above everything else in this list, a clear and well-understood goal is the key to making any group effective and to make any meeting productive. Whether it’s a conference call about a draft manuscript or a graduate student society group at your university, there should be an understanding of the goals and objectives of your group’s activities. The goal doesn’t have to be complicated-it can be “To write a paper by May 2017” or “To organize events for graduate students at our University on a regular basis”, but doing anything without a goal in mind can lead to tangential discussions and unproductive meetings. Having a goal doesn’t mean everyone in the group will simultaneously know the process to achieve the goal. If the goal is simple then the process is easily understood (e.g., if the goal is to write a paper then you get there by writing the damn paper), but for more nebulous events like lab meetings the goal or process can be unclear. Are you there to give an update to your PI on what you did each week? Or maybe to summarize a month’s worth of findings as part of a longer presentation? Or does your PI simply feel that your group ‘needs’ to have a lab meeting and you end up suffering each week through two hours of the same rambling comments as the week before? Identifying the overall goal and how to get there can alleviate the need for long, drawn-out discussions or just meeting ‘because we should’. - Clear expectations of who is doing what task. As with having a goal and knowing how to get there, an important part of group work is actually doing the things you talked about in the meeting. It’s great to generate new ideas, but leaving these ideas on the table without a clear picture of who will take up what charges can lead to you coming around to the same table again in a month’s time with nothing new to discuss. In a formal meeting setting these are usually drawn up as ‘action items’, but if you are feeling less formal you can always just refer to them as a to do list. Drawing up this to do list is usually the job of the group leader, but if your meeting is more informal you can help in productivity by offering to keep track of action items and who is responsible for which task. You can then link these tasks back to the goals of the group and see if what the tasks contribute to achieving the initial goal. If not, then the task can be considered less of a priority. - An engaging leader who listens and directs. Leaders have to take charge and direct, but they should also be good listeners and people who get other members of the group to engage. At the same time, they should be people who keep tangential discussions to a minimum and will change or redirect the topic as needed. Depending on the type of group, this could be either an elected or an informal position, and most of the time you won’t get to pick who this person is. If you feel like a group you’re working with is lacking in this type of leader and also doesn’t have a formal set-up for who directs the meeting, feel free to talk to the group members and give it a try. Offer to lead a conference call or a lab meeting and see how it feels to direct conversations and discussions. At some point you’ll have to do this kind of work anyways, so ‘practicing’ in a less make-or-break setting can help when you do have to take a lead on a project that directly belongs to you. - Deadlines that aren’t arbitrary but can still be flexible (to a point). No one likes deadlines, but they are a part of working life and should be ascribed to whenever possible. That being said, a good way to motivate your group is to have deadlines that mean something. Instead of ‘Finish your part of the proposal this in by Friday because we need to finish it,’ spin it as ‘Please get this to me by Friday so we can send the proposal to the University Organizations committee for consideration next week’. This shows the group that what you’re doing has a reason for needing to be done when it should be done, and isn’t due to your own personal whims or schedule. There will always be a task or two that falls behind schedule, whether someone forgot about what they were supposed to do or had an unexpected trip or other deadline turn up. If you’re active in the group, be ready to help out and get other tasks done that really need to be done, and if someone crucial is being slow then be ready to remind them a few more times before handing off the task to someone else. - Participation from all the players, not just the leader or a select few. This is where both you, as a participant, and the leader of the group come into play. A good leader should not only listen, direct, but also ask for feedback and participation from other group members. People may not always volunteer opinions or offer to help with a task. If you know someone has something good to say or might offer some support for a task that needs to be done, asking that person directly is a good way to get them involved. That way it’s not just the outgoing ones that get involved with the work, but the quieter ones that may not want to speak up in a group setting. You can also follow up with them after a face-to-face meeting by email, where less outgoing people might be more comfortable expressing themselves. - Celebrate successes and learn from mistakes. As with the rest of your scientific career, the success of groups you are involved with will be a mixed bag: some things will work fantastically, and others will fail miserably. A successful group is one that takes the good with the bad, and one that celebrates and thanks its participants for achieving good work, and looks back and tries to learn from the things that didn’t work out. So now that you’ve got this list, every meeting you go to will be a good one, right? Right? Unfortunately bad meetings are a part of life, no matter what type of job you have. But you can make bad meetings better by putting this list to practice: by encouraging your group members to have goals, to think about leadership styles and engaging all members, and to help out when you can in getting ideas off the ground or moving on from a topic that’s been droned about. Even group members who aren’t leaders or organizers can have a huge impact on productivity, and actively participating and getting others engaged can help you get remembered by the folks in charge. And with that we’ll close off our post with The Zep, who more than anyone knows you’ve had your share of good and bad. But yes, you do still have to care, and by caring you can help take a meeting from bad to good. Just think of all the times* you could listen to Stairway to Heaven if you help bring a meeting to a close in a reasonable amount of time and get an extra 30 minutes in your day? *Approximately 3.75

With the holiday season rapidly approaching and with the stress of year-end work diminishing everyone’s immune systems, it’s time to be on the lookout for any signs of impending sickness in you and your colleagues. In addition to the cold or flu, the stress of finishing the year while reflecting on your work in the lab can bring about an ailment known as ‘imposter syndrome’, a common condition among academics and researchers ranging from graduate students to full professors. While there is no complete cure for this ailment, with this guide you can recognize the symptoms and prevent any unnecessary flare-ups that may cripple your productivity and/or your Christmas spirit.

What is Imposter syndrome? A sufferer of imposter syndrome feels that they are unable to fulfill their career goals, that any accomplishments they have achieved are due to dumb luck and not to skill or level of expertise, and that they are simply not cut out for a career in research because they are not as smart/skilled/outgoing as their colleagues. The holiday season offers a time to reflect on the year behind and a chance to prepare for the year ahead. It also entails finishing up lab work, writing up end-of-the-years reports for projects, and having to place orders and spend grant money before the financial office closes, which can compound the normal stresses already surrounding the holidays. Scrambling to get things done before heading home for the holidays can leave anyone with the feeling of ‘Why am I doing this all NOW?’ and ‘What exactly have I been doing all year?’. These questions then create a prime target for imposter syndrome and its counter-productive symptoms. What are the symptoms of imposter syndrome?

In addition to the rushed and hurried lead-up to the end of the end of the year, time spent reflecting back can lead you to feeling like you didn’t do anything productive all year long. Maybe the year didn’t bring you as many results or papers as you’d hoped for. Maybe a crucial experiment for your thesis didn’t work the way you thought and you had to go back to the drawing board. Maybe you just went to a lab mate’s graduation party and realized how far away you still are from finishing your PhD project. These thoughts, coupled with the already high stresses of the holiday season, can lead to making one feel more like an imposter or a failure than during the rest of the year. It’s easy to look back at our own year of work and compare it to the work of other students, post-docs, or professors, and see theirs as being much more worthy than our own. But the comparisons aren’t always even, and depending on the field you’re in or the type of work you’re doing, there might be a lot of depth to your year’s worth of work that can’t be seen as easily by anyone but yourself. Think of an iceberg, where the part above water may look unimpressive but the real bulk of it lies beneath the surface. When you feel stressed about what you’ve accomplished in a year and feeling like you’re not worthy of this type of career, take a closer look under the surface. Maybe you don’t have all the manuscripts done that you’d planned, but you made nice figures for a recent conference poster and can use those and a few tables as the bulk of a manuscript. Maybe a big experiment didn’t work the way you thought it would, but it led you to a new direction that no one else has been down before. Maybe this wasn’t your year to graduate, but that doesn’t mean you didn’t do meaningful things in the lab that can give you strong momentum for the next year: optimizing assays, writing code, running simulations, going to a conference and hearing great talks and getting new ideas, doing a literature review for your thesis that helped give you a bigger picture perspective on your work. Not all of these things will have a tangible, surface-level impact, but they will provide the necessary depth of knowledge and support for you to start off the next year of studies and work with the tools you need to succeed. Graduate students and early career researchers are especially prone to getting imposter syndrome, as we’re in the point of our lives where we’re doing the day-to-day lab work required but at the same time thinking about possibilities for our future careers. When you struggle with trying to get PCR to work or spend an afternoon trying to understand one paper, it can be hard to look at a professor’s life and see yourself as able to do something similar. But take a closer look at the people we feel imposter syndrome about: They’ve spent quite a bit of time getting to where they are by doing the type of work that you’re doing right now, by running into problems and figuring out how to solve them, and now teaching you and your colleagues how to do the same (with some professors being able to pass on their lessons better than others). The work you’re doing now is not meant to tell you if you’re cut out to be an academic or a researcher or not, it’s meant to show you how the process of research works in practice and to provide you with your own depth of knowledge and support as you work and progress to the next stage of your career. You don’t have to be perfect the first time around to become a great researcher-very few of them got it right the first time, either, they just got good at not being wrong quite as often. In academia you work with the cream of the crop, researchers on the top of their game who are pioneering work at the very edge of technology and understanding. Academics have to sell their research and to conduct themselves in a very confident way, making them attractive for collaborators and funding agencies: Anyone looking into this field without that same level of self-confidence is likely to feel like they don’t belong. How can you treat imposter syndrome? Imposter syndrome has no cure, but you can take prophylactic measures to prevent flare-up using the following measures:

Prognosis Academics and researchers suffering from Imposter Syndrome tend to recover rapidly with treatment, although many will experience remission before retirement. Prognosis is generally good for those who prescribe to self-esteem building activities, personal development, peer interactions, and an optimistic outlook on the future. Best of luck to everyone finishing out the year. We’ll have one more post to close off 2015 and are excited for what’s ahead for Science with Style in 2016!

The Lakes District offers some of the UK’s best scenery and is a popular destination for weekends and summer retreats. Before I moved to England for my post-doc, a friend of mine took me for a day trip to the region during my visit to Durham in 2013. It was a spectacular mid-August day, with not a drop of rain and just a touch of wind. I remember looking down into the valley from the summit and feeling like it was a scene taken straight from The Hobbit. Another trip to the area a year later recalled a similar mood: with gorgeous greens contrasting stony heights and shimmering lakes, who wouldn’t want to spend a weekend wandering about this amazing landscape?

But as much as I and the rest of England love the Lakes District, it has a notable and well-earned reputation for crappy weather. Storms can come from nowhere and leave you wet, cold, and uncomfortable, and summits that leave you exhausted even after only a 1km ascent. After the two previous sun-filled summer trips, my husband and I went by train to hike around Lake Windermere in March of this year. While not expecting the lavishly sunny warmth of our last visit, the ever-present fog prevented any sort of view that day. This past July we made a full weekend trip to try to summit the tallest peak, Scaffel Pike, only to finish summitless due to disorienting fog before becoming drenched to the bone by cold driving rain, shivering in the car ride back to the hostel and spending a good 20 minutes in a hot shower trying to warm up again.

I thought back on these previous Lakes District jaunts this last weekend, as we headed to take on Scaffel Pike a second time. While the leaves hadn’t changed to their autumn colors like we had hoped, we were rewarded with a fantastic weekend at Wast Water Lake: no rain, small crowds, and a chance to breathe fresh air and stretch our city legs. At the same time, I couldn’t help but reflect on previous hikes, as well as my own ongoing ‘journey’ through a career in science. While I’ve already drawn parallels between getting a black belt and getting a PhD, I can also see a parallel between the joys and challenges of the Great Outdoors with those of becoming a professional scientist. Both offer challenges, opportunities, and rewards, and the parallels between the two can give us insight and perspective on how we should approach the hard times we inevitably encounter while navigating our way to a rewarding career. Be prepared and ready to adapt. A day on the peaks can be glorious or it can be dreadful, sometimes back and forth in the very same day, so be ready for hot, cold, wet, and/or windy weather. Carry a good map, plenty of water, and some extra socks, although after your first hike or two you’ll probably learn the hard way what you really needed in your bag. At the start of graduate school, I thought my undergraduate coursework in biology and chemistry would be all I needed to start research, but I quickly found out this preparation wasn’t enough. So I got deeply familiar with the literature, learned to optimize assays before running important experiments, and reached out to advisers and professors when I got stuck. These are the things that kept me dry through rainy spells of my PhD project. Know when to take in the scenery and when to keep going. While the summit or the trail’s end might be the ultimate goal, knowing when to enjoy the moments before the ultimate goal, and when you need a break to help you get to that goal without being exhausted, will make the trip more rewarding. At the same time, there will be times when you can't make a break at every view point and moments when you need to push through a bit of discomfort or tiredness to get to another milestone along the trail or a more sheltered place before the rains head in. As with the previous post on rubber versus steel, the key is to maintain a trajectory for your ultimate goal while recognizing that if you just push for that goal without stopping you’ll miss so much along the way (and arrive at the end exhausted). Stay focused so you don’t trip, but don’t forget to look up now and then to see where you’re headed. Some parts of the trail will be easy, where you can look around at the sights along the way, oblivious to precisely where your feet land. Other times there will be boulders, steep drop-offs, or slippery rocks that you’ll need to watch closely as you walk. As a scientist, there will be crucial moments that require your full attention: a technically difficult experiment that you get one shot at, planning an annual sampling expedition for the two weeks of the year that you can get samples, or writing code that will take months to run before you get an answer. When these moments come, give your focus to them and think about each step you take, and what can go wrong at each point, in order to achieve success during that crucial moment. At the same time that staying focused on one step at a time is important, don’t forget to look up now and then and see where you’re heading to make sure it’s still in the right direction. It’s easy to think that because we’re still on a trail that we’re going the right way, but oftentimes we might find ourselves on a side path we never intended to be on if we are only looking one footfall ahead at a time. If you find yourself staring down at the same assay or experiment over and over again, take a look at the bigger picture and see if it’s still the right direction. Even if you thought that this was the right way, it might turn out that the data is trying to tell you otherwise, but you may need to look up from your pipettes in order to see it more clearly. The journey is better with friends. There are times when a solitary hike is a good thing, but more often it makes for a better time when you share the road with friends. You’re less likely to feel bitter in a downpour or to get mad at yourself for missing a turn if you’ve got good friends and colleagues who are on the same road with you. At the end of a long hike you’ll have someone to laugh with about the casual mishaps and to exchange stories with at the trail’s end pub, celebrating feats of strength and good views and commiserating with each other about the rainstorms and the sprained ankles. While you may be the only one wrapped up in your specific project, you likely have a lab or an office full of other students or researchers who are on the same journey as you. Share your joys and challenges and listen to theirs in return. Even if you’re working on completely different topics, you’ll often find a lot of intersections you can meet at or parallels between your separate journeys, whether it be rejected papers or terrible lab meetings. Keep these people close during your own journey, and let them remind you that you’re not out there in the wildnerness on your own. There will be ups and downs. Some hikes you’ll do will be fantastic, sunny, and you won’t get lost or even tired out. Other hikes will absolutely suck, it will be rainy and windy and you won’t even get to the summit, or you’ll get there and there will be nothing to see but a giant cloud. Likewise, some experiments will work the first time around, you’ll have beautiful results for publication, but other experiments won’t work at all, or you’ll get results that confound everything you did already and you’ll sit there scratching your head about what to do next. The key is to persevere through the rougher times, knowing that if you keep on going you can reach another valley where the sun is shining and the p-values are significant. Part of the destination is the journey. As many millions of ways as it’s been said before, it’s not just about where you end up but how you get there. If you get to the end exhausted and not having seen what was along the way, was it as worthwhile as it could have been? If you went straight to your destination without facing challenges or enjoying the sunshine, did you learn as much as you could have? You learn as much about the end result along the journey itself as much as you do just from arriving at the end. The gear you really needed and what was superfluous, what trails led to something good and which ones got you nowhere, and finding the balance between the moments of intense focus and moments when you just enjoyed the walk. When you actually get there, you’ll recognize the importance of every step you took more so than when you’re on your way. I had this stark realization at the end of my PhD defense. I gave an hour-long seminar about 4 years of work, then I was asked a few questions about future experiments and experimental design for maybe 45 minutes by my graduate committee. Then I was done, and in a matter of a few minutes deliberation and signing paperwork, I had a PhD. My first thought wasn’t exuberance, it was … Really? That was it? And now I’m a PhD? I felt a bit cheated, like I hadn’t done enough to warrant the end result of becoming a doctor. Soon enough you realize that it wasn’t that hour-long seminar and a few questions that got you the PhD but rather the 4 years of work that led up to it. The years of staying focused on answering questions while knowing when to take a side path and explore something else, of pushing through the rainy days while enjoying the sunshine when it came, and also writing a really long, probably rather boring 182-page word document. But that’s a topic for a future blog post. One of the things I love most about hiking is that it’s one of the things that truly anyone can do. You’ll see everyone on the trail: from the power couple with matching Gore Tex jackets, a laminated topographical map, and a portable oven for making steak and ale pies on the summit, to the stag party guys in tennis shoes and jeans. While everyone comes to the mountain with their own set of gear and motivations, we all get up the mountain the same way: one step at a time. With the right mindset, navigating to a rewarding career (or just getting through your PhD) is something that everyone can do by taking it one step at a time, by being prepared, and by learning from the journey as much as working towards getting to the destination. How to make a fulfilling break: Using your time away from work to achieve a better work-life balance9/9/2015

People like to comment to me about how much I travel, asking where I’m jet-setting off to this weekend and if I ever stay at home. I’m not sure how to respond sometimes. Most of the time I’m proud of all the places I get to see and things I get to do, but occasionally the comments make me think that I travel a bit too much. This feeling is greatly enhanced by the irony that this week’s post is currently being written from a hotel room in Dublin on a RyanAir-enabled weekend away from home (with flights so cheap, why not?). While marking off cities and countries from my massive travel to do list is something of an obsession of mine, it’s also one of the major ways I unwind. Spending an afternoon wandering the side streets of a new city on the look-out for hidden cafes and photo-worthy architecture or scarfing down a ham and cheese sandwich on the summit of a hike are things I greatly enjoy. More importantly, these adventures, both big and small, help me unwind when I’ve been twisted and my tightened by stress, responsibilities, and the daily grind. Traveling allows me to rebuild my respective, refreshes me, and leaves me feeling ready to tackle my work's problem when I get back home.

So often as PhD students, post-docs, and senior academics, we feel like we just can’t take a break, as if something just has to be done right away. While there certainly are moments when deadlines and teaching commitments and emails pile on us endlessly, a lot of the ‘academic guilt’ comes during times when our workload is at more of a steady state. We very easily let ourselves fall into this mental trap, in which we think we should be doing something at every given moment: reading/writing a paper or getting lab results analyzed or trying to find a date for that continually-rescheduled meeting with your collaborators. Academic guilt is necessary, to some extent, for academic life to function, since a full-fledged academic is essentially their own boss and has no one to tell them during the day when they need to get back to the grind. At the same time, too much urgency can be a hindrance both to our productivity and to our work-life balance. For those of us working in academia, it's crucially important to balance our work with our personal lives, using well-timed breaks coupled with periods of sustained work. Scientists seem to be pretty good at the periods of sustained work part, but can be terrible at the well-timed breaks part. The key with taking breaks (and not feeling guilty about it) is to make each break a fulfilling one, one that leaves you energized for the rest of the day or week ahead. There are many effortless alternatives to working, as any Tumblr and Netflix binger knows all too well, but simply not working is not always a fulfilling break. In order to have a fulfilling break, one where you come back to your problem with a clear mind and a go-get-it attitude, you should use your free time to purposefuly unwind, unthink, un-everything. We all need moments to scroll through the vast wasteland of the Internet or to watch our favorite TV series with a glass (or three) of wine, but in order to come back to work the next day or after the weekend ready to tackle what you left unfinished, your free time can’t be spent with only these types of breaks. A break can be a large one or a small one, maybe a lunch outside on a sunny day or a Saturday out with friends instead of working on that experiment that just ‘has’ to get done. Whatever your schedule and needs are, a fulfilling break should enable you to do the following things: - Step back and see the bigger picture of what you’re doing and why you’re stressed about it. If there’s a hard deadline for a paper resubmission or grant application, it’s easy to see why getting things done for that time is stressful. But what about those moments when you feel rushed but don’t really have an explanation? A lot of the times that we feel stressed, we may not even know why and there may not be a concrete reason for it, or we might be making a mountain out of a molehill. Many people respond to stress by working, even when the stress originates from some other part of our life and issues outside the lab. Maybe your 10-year high school reunion is coming up, where you know all your classmates will ask what you’ve been up to for the past 10 years, which somehow triggers your memory into remembering that you didn’t work on that manuscript for a few weeks, and then, What have I DONE with my life, why didn't I just get a 'normal job' like all my other classmates, and also why do I have nothing to wear to the reunion? At times like this, its important to take a breath and consider whether getting more data points is really the solution for addressing what may be some bigger issue that has nothing to do with your research. At times like this, that weekend trip to the lake or an evening drink with friends instead of working nonstop can give you a better perspective on your life, your stresses, and the necessity of stepping back and taking a deep breath now and then. - Let your mind refocus when you run into problems. Problems in science tend to require a lot of focus to figure out. Why did all my cells die? Why am I getting this error message while running the data processing script that was working perfectly 2 days ago? Staying focused is good, but if you stare at something for too long you’ll lose your sight along the periphery. You can easily end up banging your head against a problem trying to throw everything you have at it, only later to recognize the solution while walking out of the building three hours later. Taking a step back from a problem, difficult or simple, is a good strategy because it gives you a chance to think about all the components of what you’re working on instead of the one thing that’s giving you trouble. Often times the solution was a simple one, maybe you forgot to add serum to your media or you saved your data file as a different format. Taking a break at the moments when you get the most frustrated can help allow your brain to get to those ‘a-ha!’ moments of remembrance and insight that can’t come when you’re staring a problem in the face and letting it get you flustered. - Let your brain disconnect from work, as much as it can. It’s difficult to unwire ourselves completely from our work, especially with those 11pm emails from your advisor asking what you’ve been up to in the lab for the past week. As hard as it may be, work on setting aside a part of your day and your week when you don’t check emails or work on the pile of data/papers you brought home. This gives your week more structure that you can fill with a fulfilling break, knowing that you won’t have to be bothered by some science emergency (which usually ends up not being a real emergency at all). Professors do tend to send emails at odd hours, perhaps due to their own odd life-balance, but likely it's because they just enjoy science that much and want to know what you're doing. It's both full-time work and hobby for some, but remember that you don’t have to reply to every one of their emails instantly. Most likely they’re releasing a barrage of emails to all their collaborators and students at once when they have a free moment, so don’t always feel like you’re being singled out. - Have Internet-free moments. In the wired workplace especially, this goes hand-in-hand with disconnecting from work. Whether it’s during the work week or on the weekends, take some time to unplug from your laptop/tablet/phone/whatever. Go to a museum with a friend, take a long walk somewhere new in your town, or go out to dinner and leave your phone on airplane mode. It’s hard to unplug when you have the world in your pocket 24/7, so when you have moments where you can enjoy the moment, be sure to do so. - Take time to focus on a different problem/idea/concept/activity. While binging on the internet and Netflix can help us disconnect, it’s not always the best way to focus away from work. We can get good at multi-tasking, watching TV at the same time as checking our phones or reading a paper. So make your brain take a break by thinking about something else. Read a Sherlock Holmes story and see if you can figure out the case before he does, dig our your oil pastels from your high school art class, learn how to say ‘the turtle drinks milk’ in a different language, or call your grandma and ask her if she has any extra knitting needles. Whatever suits your style, find something that you’ll enjoy doing that provides an external focal point for your brain, something that’s not as easy to let professor emails and thoughts of your next experiment slip in without you being ready to tackle them at your desk the next day. To find your ideal fulfilling break, all you have to do is look for something that fits your style, something that helps building you up when you’re feeling down and that unwinds your knots when you’re twisted around. My fulfilling breaks come both from travel and from tae kwon do. Both give me a reason to not check my phone for emails for blocks of time. Both give me things to focus on, like figuring out which trail or street to follow or remembering all the moves in my pattern. Both make me feel happy when I’m done (even though I may be physically exhausted from endless walking or kicking, depending on the activity), and that good feeling reflects back on the rest of my life and my work. Both take time away from when I could be reading papers or analyzing data, but when I do come back to work I feel like I have energy and take on those tasks with more fervor than if I just trudged through them constantly. I can also enjoy both at different time scales: tae kwon do is there twice a week to finish off a day in the lab, and travel is there on the weekends to clear my mind after a busy week (or two). There are also strategies you can use to relax during the work day to keep yourself from feeling like you’re banging your head against a problem or when you fall into a pit of unproductivity: - Take a walk. This is especially good for those of us that spend most of our day at a computer. You’ve likely already heard the lecture on taking a break from staring at your computer monitor so you don’t go cross-eyed, but stepping away from your monitor is also good for a quick 5-10 minute mental unwinding at work. If you feel yourself being unproductive or opening a few extra tabs of buzzfeed articles, take a walk somewhere in your lab building or make an excuse for a short walk around campus. A trip to the corner store or a lap around your building gives your eyes a chance to re-focus on the world and can let your brain think about the idea or problem you’re working on when you don’t have it staring you back in the face. - Have a fika. No, its not a new Science with Style candy bar (although that could be a good way to pay for the URL registration). ‘Fika’ is a Swedish word/concept which means ‘to have coffee’, but it’s more than just a way to get some extra caffeine. Fika is having a break with colleagues, friends, or family, and if you work in Sweden then you’ll even have a dedicated break time during your work day. It’s a time when you socialize but also to take a step away from your work for a few set moments of your day. You may not get a set time off from work (or have any fikabröds to go with your coffee) but you can start your own fika trend with office mates or lab mates and bring some of that Scandinavian culture to your own daily schedule (IKEA mugs and blåbär juice are a great fika starter kit, and tea is an appropriate substitute for those who prefer their caffeine from other sources). The hardest part about taking a break is that there are times when we feel like we just can’t. When we feel anxious about getting something done or that something MUST be figured out right away. The thing about a career in science is that it’s not an easy job to have. A lot of the answers are unknown and won’t always come to you easily, especially if you’re in an endless staring contest with them. Recognizing where your stresses come from as well as recognizing when you’re stuck can help you not only figure out what you can do to feel better but also to move forward with a problem and be more productive with your work. Any job, and science especially, comes with a lot of external pressures and stressors, but staying focused on the bigger picture of your world can help you face the stresses that you have to face and keep at bay the ones that you make for yourself. And now as this post is ready for some editorial wrap-ups, I can feel free to wander the streets of Dublin again before my flight back home and another week of work. Before taking my 313th flight (yes, I’ve counted the total number of flights I’ve been on in my life. Everyone needs a hobby!), I’ll pop over to the Porterhouse brewery to enjoy some Irish music and a final pint, knowing that I’ve crafted a decent post to self-validate my incessant need for travelling. But while there’s still free wi-fi, I might look into the weekend flight prices to Prague in the autumn, as I’ve heard that Czech beer (and sightseeing) is divine!

In the first blog post, I gave an overview of the definition of style and how this concept relates to how we should think about doing science. Now after some philosophical discussions as of late with colleagues and after a morning spent pondering over this article by 538 about p-values, retractions, and how science is a lot harder than we usually give it credit for, I wanted to take the time to go back to giving a definition to the first part of 'Science with Style'.

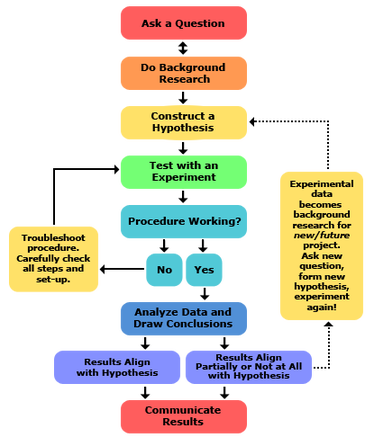

We should not only think about and define the components of 'Science with Style' but we should also think about what getting a Ph.D. really means. Is it a degree of ‘Phinally done’ (as my UF alumni bumper sticker says) or ‘Phucking Do it’ (as your advisor might say) or ‘Piled higher and Deeper’ (as Jorge Cham says)? No, because the Ph stands for ‘philosophy’, and earning a Ph.D. means you shouldn’t just be an expert at pipetting or counting cells, you should be an expert in being a scientist . So what does the dictionary say about science? Science, noun: ‘The intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.’ Breaking down this definition piece by piece, we can see that science is meant to be more than just doing science. We can spend all our time in the lab generating data the rest of our lives and endless hours pouring over endless spreadsheets of results, playing with variables and looking for every possible combination of factors to tell us the meaning of the universe. As graduate students and post-docs especially, we spend a lot of our time as scientists-in-training doing science, but is that the same as being a scientist? Part 1: ‘The intellectual and practical activity’ Graduate students and post-docs likely understand all too well the ‘practical activities’ that go into science. Although perhaps it’s a different issue of whether you want to call trudging to the lab at midnight on Christmas Eve to collect 12-hour time point samples or renting a 4X4 so you can drive to the middle of bear country to collect water samples ‘practical’ or not. In the early parts of our careers as scientists, our lives are dominated by the practical activities: rats to dissect, seeds to count, cells to split, livers to grind, surveys to conduct, field sites to map, machines to fix, data to normalize/analyze/synthesize/everything-ize. To non-scientists, and to many of us scientists that got interested in exploring the natural world at a young age, this is what science looks like, the clips they show on TV and movies of scientists making genetically engineered dinosaurs or solving crimes with fingernail clippings. But the problem is that this is only half of what science is defined as, and only half of what science actually is. Especially as young scientists, busy with all of the practical tasks required to graduate or publish or get out of the lab by 9pm, it’s easy to forget about the intellectual side of science. There’s a reason for those 12-hour time points and water samples from bear country: you’re setting out to answer a key scientific question in order to address a specific hypothesis. Most of the time, especially in graduate school, this question and hypothesis wasn’t first crafted by you, but rather is part of a large grant your PI received or is related to some data that a previous student/post-doc collected 5 years ago in your lab. You’re expected as students to know the reason why you’re doing what you’re doing, but for most students you weren’t a part of the brainstorming and data analysis sessions that went into crafting your project. At the same time your PI is likely balancing other students’ projects and thinking ahead to other grants and collaborations, and may at some point have forgotten that afternoon sitting in their office when they came up with the brilliant idea that is your project. This doesn’t mean that you’re doomed to some irrelevant project from years-old data or some idea your PI came up with in a caffeine-fueled brainstorming session that they happened to end up getting money for. As a scientist-in-training, your training includes both the intellectual and the practical sides of science, so you should focus on both of them. Do what you need to do in the lab, but before you run off to collect that 12-hour time point, go back to the beginning and think about the greater why of that time point: - Go back to the literature related to your project. And don’t just read the papers, think about how they did the experiments, the statistics and conclusions that came out of them, and whether what they say they found is what they actually found. Read not just for facts but to synthesize what’s been done before and how it all connects. - Approach everything you see with your own logic and let yourself see the data without the author’s or your PI's interpretation. Look at everything at a critical angle before you accept it as a (potential) truth. Science was made for cynics, not optimists, so take everything you find with a grain of salt! - After you get a handle on the literature, do an afternoon brainstorming session of your own. Where are the gaps in knowledge? What was observed that couldn’t be explained? Where is there a question that’s been left unanswered? This may not look like science to you or to most people who think of TV and movie science, but this is where the difference between doing science and being a scientist lies. And how we go about being a scientists and answering these unanswered questions lies within the scientific method. Part 2: The ‘systematic study’ At some point when your primary school teacher was getting your class ready to come up with a science fair project, you probably had a diagram similar to this hanging up somewhere in your classroom. This one comes from a science fair project website and just because it was made for 13-year olds doesn’t mean you shouldn’t print it off immediately and hang it in your office:

At some point the scientific method was probably covered again during your undergraduate studies, maybe even in more than one of your courses. This all likely seemed too easy and common sense when you were 13, and your brain was soon filled with more important details like chemical reactions and math equations and the entire Krebs cycle. The issue is when we get so bogged down with the practical parts of science that we forget about the common sense/intellectual parts of science. It’s easy to get lost in the details and the experiments that you have to run to get data, but if you don’t understand why you’re doing what you’re doing, you’ll end up flailing away in the lab running a thousand different assays without any clue as to where the meaningful answers are.

The scientific method may be common knowledge when you look at it, even 13-year olds can get the gist of it, but we can’t push it aside or think that the details are the only thing that matter. The scientific method is the heart and the core of science as a field of study. It’s what makes science science, a field of study where we are trying to figure out ‘the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world. ’ We do this not just by banging our heads against the wall or coming up with things out of thin air, but with a systematic study that we follow for every single thing that we do, if we are to call ourselves scientists. But when bogged down with the details and practicalities of science, where do we start in order to make progress towards making sense of the world? We go back to the beginning, once again: We ask a question. Part 3: ‘Observation and experiment’ Look back at the start of the scientific method diagram. Where does it begin? With a question about why you’ve seen something. In the case of your work, what you ‘see’ is what the literature in your field has told you already. What did someone find but couldn’t explain with what was already known? That’s what you’re setting out to do: to explain something that’s currently unknown. The observation part is what we do to understand what’s known and to help us ask a good question. The experiment is what we do to understand what’s not known and the work you do will lead you to an answer. And it’s not a good answer or a bad answer, it’s just an answer to your specific question. While you can debate on the relevance of 1100+ significant p-values in 538’s article (perhaps there should be a multiple testing correction added into the widget), the take-home message in regards to science is this: The key part of science isn’t in finding good answers, but in asking good questions. You can play around with variables and experimental designs and will likely find different results every time. There’s a million ways to find an answer, and changes in policies and ideas about science are indicative of this: eggs are good, eggs are bad, don’t eat carbs after midnight, carbs don’t matter, Pluto is a planet, no it’s not. But what’s at the crux of science isn’t the answers, it’s the questions. And when you ask good questions, the answers you get back (regardless of what they are) are the meaningful ones that withstand the test of time and replication. So whether you just desperately want to be 'Phinally Done' or are setting out to 'Phucking Do it' or feel like you're always 'Piled higher and Deeper', remember that what you're towards is becoming a Doctor in Philosophy, and that a Ph.D. is not just about doing good science but in becoming a great scientist.

Maybe it’s cheesy to use martial arts life lessons in a blog like this, but the comparison is actually quite relevant for graduate school/academia and life as a scientist in general. Probably the most relevant parts are the lessons you get on how to take hits and to keep on going, especially relevant when you feel like you’re constantly getting your ass kicked in the lab (metaphorically speaking, of course). Looking back on earning my black belt vs earning my PhD, a lot of the best lessons learned from martial arts and academia are applicable for both parts of life, and the first of these that I’ll talk about is failure.

I recently tested for my blue belt in tae kwon do through my new school here in Liverpool. I already held a black belt from my original school in the USA where I started practicing during high school. With different schools having different standards and licensing groups, my USA black belt was ‘non-transferrable’ here in the UK (something about having done the forms on the wrong side of the road). Either way, I was happy with the chance to get back into training this past year, especially after nearly a 10-year hiatus while I was busy in undergrad and grad school, and the chance to work on my skills even when I was again starting from scratch as a white belt. Tae kwon do belt gradings are not to be taken lightly. The high-ranking belts that are there in front judging you are there for a reason: because they’ve worked hard to get to where they are, they strive for excellence in everything they do, and they expect that someone looking to get to the same level as them meet those high standards. It’s an intense event, doing your forms and sparring with these high-ranking eyes watching you the whole time, yes sirs/ma’ams every time you’re asked to do something, the ever-present pressure to perform your best while at the same time you’re so nervous and tense as to not make any misstep. It was a strange thing to be back again on the floor 10 years after testing for my black belt, this time in a new country and new instructor and with a PhD under my belt (no pun intended). Getting ready for this testing and trying to focus all my nervous energy into something positive, I found myself reflecting back on previous belt testings from high school and how this one might differ now that I’d also gone through the rigors of grad school. Flash back to February 2005 when I was at my first black belt pre-testing. Anyone going for a black belt had to go through a pre-test before the actual test, in case one testing wasn’t enough. I had been studying tae kwon do for 3 years at that point and had been a brown belt for quite some time. I was flexible and strong and always gave every move 100%. Previous testings had all gone well for me, with decent scores and the instructors recognizing my skills, my energy, and my intensity. Except for one thing: I was terrible at breaking boards. In reality, I wasn’t terrible, I COULD break the boards but I was generally nervous about the whole ordeal. I would easily become frustrated in class when we had to do them because it wasn’t coming as easy as the rest of what we did in class. It was about precision, timing, hip movement, etc, but most importantly it was about not being afraid of the board. Any hesitation, any thought that you’d hurt yourself, if you tensed up instead of being relaxed, meant the board didn’t break. And as with any failure, each board that didn’t break seemed to make the next one look even harder to break. During the lower belt testings this wasn’t a problem, because you always had multiple chances if you didn’t break the board on the first go, you or your instructor could give you a mini pep talk and you could get through it. Now that buffer was gone: going from brown belt to black, you had one shot per board, and four of them to go through. So there I was, at my first black belt pre-testing, terrified out of my mind. I knew I had to break boards that night, in addition to all of the other forms, my current brown belt pattern and all those from previous belts, sparring, knowing facts about which Korean philosophers and historical figures that the forms were named after. My nervousness about the boards permeated in the rest of my testing. I wasn’t the confident girl who had impressed everyone with her intensity and strength, I was tense, frightened, and waiting in nervous anticipation for the time when I had to break boards. And what I was afraid of most was failure. After a nervous pre-testing session, I failed at the first board. Right elbow strike. It hurt more than the sore elbow. I went back home and back to training, tried new break techniques for the hand strikes. I was still nervous though. Another failed pre-testing and I think that was the point when I and my instructor realized I wasn’t ready yet. In between the failed pre-testings I graduated high school and had that blissful summer between being a kid and being an adult. I had failed in my goal of getting my black belt before graduation, but I realized I hadn’t failed at getting my black belt. I just hadn’t gotten it yet. The start of college was an exciting time, new friends and a newfound confidence. I enjoyed the freedom of picking my own classes, felt like I was on the right path in my life in terms of my program in environmental science, and I was resolved overall to succeed at the life I had set out for. Pre-testing came again and this time I felt different-I had failed twice, I had practiced new breaks, and I changed my pre-game approach: instead of being afraid to fail, I envisioned success, knowing that I had a hurdle to pass over but that I could do it, I had broken boards in class, and now I just had to do it in front of a live audience. If a failed broken board makes the next one seem harder, the 4 successfully broken boards at pre-testing made the real ones at testing seem like paper. I went to the testing blasting pump-up jams on my car stereo (most likely Eye of the Tiger, the classic and stereotypical martial arts pump-up jam), I went through all the requirements for forms and sparring with a fellow brown belt. When it came to boards I remember that first one breaking, and all the other ones just falling apart once that first one went. Apparently at the last board I let out some sort of victory war cry (I don’t even remember that), the rest of testing and that whole day was more or less blur. Whatever else I did that day, I had finally not failed, and it felt amazing. Knowing how much you have to fail before you get things right is perhaps the hardest part about science, and it is a fact of being a scientist that no one tells you in lectures or lab courses during your undergraduate studies. Being on the cutting edge of knowledge means that no one’s done what you need to do already. The scientists whose work and whose lives have lasting legacies didn’t always get it right the first time. The key with success is not in not failing, but in continuing to try even when you fail along the way, in continually recognizing that you didn’t fail completely, you just didn’t succeed yet. And maybe this is the hard part, where we all hit a wall: that first PCR you run where no bands come up on the gel, the code that constantly gives an error message you can’t figure out, or the time you almost set your lab on fire when a chemical reaction went for too long. All these things feel like boards we couldn’t break, and if you can’t break it once what makes you think it will break a second time? The key with failure is not letting it get to you. To learn what you can from when you fail and not be afraid to fail again, and again, and again, until you get it right. My first PhD advisor said it best as I was nervous about trying a new protocol. His sage, Virginian advice was “Just try it!” and even if it didn’t work the first time, at least you learned something. The best part of it all is once you get past the hurdle, once you keep trying until you get it right, then the boards just shatter in front of you. Progress comes not from doing things right the first time but from learning how to get it right the next time, or at least the next time, or maybe the time after that, and to keep going until you get there. Back at my recent UK blue belt testing, I put this philosophy back into action, 10 years post-tae kwon do hiatus. I was certainly nervous, not only to perform well, but to make a good impression on a room full of kids and instructors I had never seen before. I told myself that if I failed I was still me, that I had worked hard to get to this point, and I would still have a chance to learn from it and try again. It’s the same speech I give myself before presentations, conference calls, PhD defenses, oral exams, the results of a gel, anything in science where you get judged and scored. No matter what happens you give it all you got, learn something when you can, and remember that you come out the other side the same person as when you went in—all that’s required of you is that you gain something from each experience. I’m thankful that this time around I earned my 4th Kup blue belt, while at the same testing I learned that I hold my guard hand too high while punching. And that’s also part of the lesson for when we don’t fail: there is always room for improvement and things to learn, even when we succeed. Come on, don’t we ever get a break??

WHAT IS STYLE?

Style, noun. 1. a particular procedure by which something is done; a manner or way. "different styles of management" 2. a distinctive appearance, typically determined by the principles according to which something is designed. "the pillars are no exception to the general style" Webster gives us a nice definition of ‘style’ but perhaps not a complete one. The term ‘style’ has evolved to be synonymous with a distinctive manner or way of appearance, more of a combination of the two parts of the definition, in the way that ‘a/the style’ is distinct from style. What style is NOT, but sometimes gets confused for, is fashion, trends, and other shallow things that look good on the outside but have no value inside. The people and things that have style are the ones that are true to themselves, whose legacies and images withstand the test of time, whose paintings or songs or movies stand out in no matter what generation or age or millennium, the ones you still feel a connection to even years after they were made. When I think of who to me has style, I think of the likes of David Bowie, how The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars on repeat will make any bad day seem better. Or one of my favorite artists Winslow Homer, how his paintings of waves and the battered coast of Maine seem as if the wind and water could knock you over at any minute. Or my childhood pet, an English bulldog named Buddie, how she did what she wanted when she wanted and didn’t care very much what anyone else thought about it, be it barking at non-existent squirrels or going for a ‘walk’ which usually ended at the top of the driveway. Style is about never compromising who you are and in letting your passion and heart shine through in everything you do (even if your passion and heart include lazily laying on the kitchen floor, a la English Bulldog style). WHY DOES IT MATTER? Style is about doing something distinctive, with substance, and in a manner or way that lets you be true to yourself. Science also has a strong need for the concept of style in what we do. And in reality a lot of what we do already HAS style: our work is distinctive by nature, we do it in such a way (replicates, validated methods, peer review, etc) that our results have substance, and we can let our passions for truth, knowledge, and making the world a better place come through in the way we present ourselves and our research. So why then do we never think about science and style in the same sentence? A recent article by NPR nicely touched on how the skills we have outside of the facts we know are so important for success. But, the question becomes, what do we call this skillset? Terms like ‘soft skills’ make it seem like these things aren’t important, terms like ‘grit’ sound too American, ‘21st century skills’ isn’t quite accurate, since it’s not just about tweets and Powerpoint. Certainly there’s some other term that encompasses this vast array of life skills, everything from how to manage your time amidst emails and meetings and getting real work done, how to present a project in 5 minutes and convince a room of people it’s worth funding, how to talk about your research when a journalist has a microphone recorder to your face and with questions coming fast. A lot of these skills can fit under the mantle of style, and it’s because of the importance of defining your personal style when it comes to making your research matter that I’ve started this blog. My goal is to use this blog as a forum for us to talk not just about doing science but in fostering Science with Style. This blog is here as a place for exchanging stories and experiences, talking about ways to better share and demonstrate the impact of our research, and to work towards helping everyone find their own style as they get ready for whatever comes next in their careers. So often during grad school or our time as a post-doc, we focus on the small things: getting that assay to work, answering frantic emails from advisors about when our results will be ready, trying to figure out if we filled out the paperwork correctly for that DEA regulated drug that we need for one crucial experiment. These things are all important but can also distract us from the bigger picture. Why did I become a scientist? Why am I stressed? Why does my work matter? Why am I running this same stupid assay for the 14th time?? WHY SHOULD WE TALK ABOUT DOING SCIENCE WITH STYLE? In this day and age, being a scientist means more than just doing science. But what does it mean to BE a scientist, and how can we go from just doing science to making science matter? In a recent study done by Princeton University, scientists as a group are seen as one of the most competent types of workers out there… but we’re far from being trusted. We work hard to make a difference in the world, be it with global climate change or air quality or cancer cures, but does the world understand what we do? How can we make a difference when the public trust the latest diet trend or journalistic scare tactic more than they do hard facts generated by the scientific method? Here lies the importance of doing science with style: We can work as hard as we can for our whole lives, but if no one understands, cares, or even knows what we do then it’s all for naught. Our advisors and bosses aren’t here to be our style guides, they’re here to help us become good scientists. Style has no formal training these days, and my hope is that with this blog I can help you on the road towards figuring out what your style is. I’ll have posts on everything from giving presentations in a way that keeps people off their phones the whole time, promoting your research to your science icon when you meet them at a conference, finding an outlet to share your work and to let your passion for science shine, guest posts from scientists in different types of jobs talking about what their days look like, and some (hopefully) humorous insights into what life as a scientist is really like. I hope that you enjoy this blog and I am looking forward to hearing from you about your science, your passion, your personality, and how you bring it all together as a Scientist with STYLE! |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed