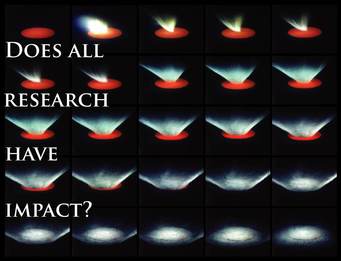

Last week I attended a seminar about new advances in clinical trials for cancer treatments. The seminar started off with one of the research leads from the University of Liverpool clinical trials research center introducing the topic and the upcoming speakers. The introduction emphasized the importance of research with impact and that knowledge for the sake of knowledge alone isn’t useful. Based on the number of problems that scientific research is needed to solve, the organizer reasoned, we simply can’t do research that doesn’t have a direct application.

I didn’t fully disagree with the cancer research group lead, but his statement did catch me off-guard. There’s certainly a lot of research that seems to go nowhere or that leaves us asking “Why did tax money go to this study?” Having a vision of what the research can lead to is a way to ensure that the work we do as researchers has meaning. But at the same time, it’s unfair to say that knowledge for the sake of knowledge isn’t necessarily useful. This also presents a challenge for science communication, since one of the ways that we engage with an audience is to try to connect them to a story by sharing its impact. The lack of an immediate impact is not necessarily a failure of science, but it is a potential barrier for effective science communication. Not everything that scientists do will be relevant, interesting, or meaningful for the everyday person—but does that mean we can’t communicate this kind of science effectively? The comments made at the seminar came at a time when I was halfway through reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I found myself deeply intrigued by Robert Pirsig’s discussion on the infinite nature of hypothesis testing. Will science inevitably continue to answer one hypothesis at a time only to have five more hypotheses appear once that one has been addressed? Will we ever have data that’s solid enough to support or refute a hypothesis, or will there always be an infinite number of counter-explanations for a given observation? Pirsig’s book wasn’t what exactly light evening reading, and maybe not the way to get people interested in science, but I did enjoy his discussions and spend some time pondering both his book and one of my previous posts on the philosophical foundation of scientific research. PhD students and early career researchers know all too well how new results often lead us to more burning questions as opposed to solid answers. As scientists, we slowly work towards conclusions about how the world works and gain, piece-by-piece, a better understanding of our world. But the progress of science isn’t always as tedious as it may feel when we’re in the middle of it. My own enthusiasm for science was ignited last week with the news from NASA about the TRAPPIST-1 system. And with global threats like climate change, freak asteroids, and American politics, it seems like a good time to get excited about potentially habitable planets that are 40 light years away! NASA news is broadly exciting for many of us, but it’s also the type of news that reflects this idea that not all science will impact our day-to-day lives. This work is science for the sake of science, for a better understanding of our universe, and quite unlikely to directly affect anyone in this lifetime. It’s the kind of story that makes for great science news, but doesn’t necessarily answer the question of “Why should I care about science?” for people who are living their own lives and who aren’t necessarily interested in the mysteries of the universe. Two weeks ago I talked about the upcoming March for Science and the goal of getting people on the side of science. While engagement is essential for the future of science, we should also recognize that not everyone will be as enthusiastic about science as we are. A recent survey from voters in the 2016 election asked people what they consider “very important” for their voting decisions. While the economy and terrorism are broadly important to most voters, only 52% of voters surveyed considered the environment influential in their voting decision. It sounds like an uphill battle at first, but with these things in mind we can come up with a strategy for the future of science communication: - Part of our message needs to reflect science as a methodology, not just a field of study. To improve science literacy, we can’t simply report more scientific discoveries but should instead emphasize the scientific discovery and hypothesis validation process. - We should write science communication stories as if we were journalists and not public relations officers. Journalists write stories that discuss a topic from as many sides as possible. If you’re promoting science as a means of reaching a universal truth, you should present the story in a way that allows people to draw their own conclusions or alternative hypothesis about a topic’s worth. - We should not be shy about the fact that not all research will be directly relevant for people’s lives. We can emphasize that scientists may need to ask “How does this work?” while holding back on the inevitable question of “Why should I care?” right away. - Scientists and science communicators can also think about how they can meet people where they are. As an example, an EPA scientist from Louisiana recently attended a town hall meeting, where her statements were met with enthusiastic support. People who are already interested in science might meet us on twitter, come to our seminars, or meet us at a museum, but what about people who might not have a weekend trip to the Natural history museum on the top of their to do list? You can also think about what science stories you connect with: Do you like all fields of science? What drives your interest in a topic? Why do you click on a news headline? There are numerous topics in science and research that are relevant for people who aren’t scientists, ranging from cancer drug trials to global warming. The stories we tell about these topics will make their strongest impacts when they are focused on the impacts to people over the science itself. But as scientists, we shouldn’t neglect the utility of knowledge for the sake of knowledge or consider people as scientifically illiterate/unengaged just because they don’t share the same curiosities as we do. Part of the goal of science communication can be in sharing science for what it is: as a way of reaching the truth that can be slow, monotonous, and mysterious—but it’s a way that we can reach incredible findings that have impact beyond our own lives. As the saying goes: sometimes the journey is more important than the destination. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed