Science communication online

Perhaps you’ve marched for science, talked to your congressional representatives, or explained the science behind global warming/GMOs/vaccines with your friends and family but are still looking for other outlets to share your scientific knowledge and passion to a broader audience. Through social media platforms online, it is now easier for scientists to embark in science communication and outreach with the general public. There are numerous ways to share scientific ideas and results with a wider scientific audience than at a conference presentation or a wider lay audience than your family and friends. Starting a blog is a great opportunity to become an active science communicator: long-form blog writing is a way to share information, teach concepts to a new audience, and engage with interested readers who are curious about your topic. Starting a science blog is not a trivial task, nor is it easy to maintain a website or keep up with a regular posting schedule. Keeping up with a blog takes time, energy, patience, and good planning. That being said, the potential for rewards for both you and your readers can be worth the effort. This week we hosted the #SciBlogHubChat and discussed the challenges and strategies for active science bloggers. Today’s post is a summary of how you can start and keep an active science blog and some considerations for maintaining your creative energies. We are also only a few weeks away from celebrating the two-year anniversary of Science with Style. It has been a fun yet challenging two years and we hope to share some of the things we learned along the way! Step 1: Lay out your blogging goals Our online presence is becoming more of a part of our lives, and our careers, than ever before. Because employers and collaborators will look at your online presence as a portfolio alongside your CV/resume, it’s important to ensure that what you say online reflects who you are and what your goals are. It’s not enough to set up a blog and let it sit there empty until you write a 5000+ word post ranting about a bad day in the lab. You have to figure out what you want to achieve with your blog and what work it will take to achieve your goals on a weekly or monthly basis. Start by answering the following simple questions: - Who is your audience? - How will you share your material with your audience? - What ways will you promote your website (Twitter, Facebook, posting on other blogs, etc) - How often will you provide new material for your audience? - How much time do you have to devote to writing posts (be sure to include time spent brainstorming ideas, reading relevant papers/articles, and conducting interviews)? Answering these questions will help you determine the style of your website, if you link your blog to a social media platform like twitter, what sort of language you use in your posts, and how long your posts will be. For Science with Style, I write posts for early career researchers who come from a wide variety of technical backgrounds; for that reason, my posts focus on professional development and science communication. For my new project, the ToxCity Tribune, I am looking to reach people who are interested in toxicology and environmental science news. I write these posts in a way that is more general in terms of discussing scientific concept and I focus less on themes that are more relevant for early career researchers such as career development. Science with Style posts tend to be around 1500 words long and the ToxCity Tribune posts are slightly shorter (1000 words). Part of this is the time required to read articles and write complex topics more concisely for ToxCity Tribune whereas for Science with Style I have time to talk more about a topic since there is less background research needed. Step 2: Set up a clean and simple online presence There are many hosting websites you can use to set up your science blog. A few examples include WordPress, Weebly, Blogger, and Wix. If you are more social media savvy than I am, you can also explore the applicability of websites like Tumblr and Reddit for your writing activities. Stick with a template that allows you to adopt a simple, clean style for your website; you don’t need anything flashy or complicated that will drown out your message. Finding the best design for your message will take time and will most likely involve you trying out a few different approaches. Be open to changing things around if the template is not working. The good news with websites such as weebly is that if you change your layout, you won’t lose any of your content. If you are using a free hosting platform, you won’t have full control over your URL; this service only comes when you pay extra for an expanded hosting package. When you are just starting your blog you can try out a couple of different websites before you commit to a paid plan and custom URL (if having one is important for you). I pay around $60 USD per year for both the URL and the upgraded Weebly package. I don’t make any of that money back on ads or revenue, but I consider $5 a month a low enough cost to feel comfortable with paying for the upgrade. If you have HTML skills then you can create or customize your own website and only pay the URL and hosting fees. This means an investment in time instead of money (unless you pay someone to do the customization). But don’t feel pressure to become a computer programming or design expert—keep it simple, clean, and invest the time and/or money into the parts that are the most rewarding to you. You might also want to develop a social media presence to go along with your blog. This can either be connected to your personal account or to a separate, blog-specific account. This will depend on your blogging goals, what type of posts you want to write (more personal or more detached from your own work/experience in science), and what audience you want to reach. If you decide to separate the personal from the professional, you can establish separate accounts to help you follow and find relevant materials for your blog and can keep your personal account for fun or your personal perspectives. I use @SciwithStyle and @ToxCityTribune to follow accounts that are relevant for each blog. For Science with Style, I follow academic professional development organizations, science communicators, and outreach-related accounts. For ToxCity Tribune, I follow toxicology and environmental science research groups, toxicology papers, science news websites, and government institutions. Having a social media account also requires you to have a social media plan in place: how often will you post on the account, how will you engage with others online, how will you share and promote your materials, whose materials will you share in return, and who you will follow. Social media can also be a distraction from work or from your writing, so be sure to limit your time to 5-10 minute increments. Distractions aside, I’ve found Twitter to be a great source of inspiration, news, and connections to interesting people I never would have met were it not for a curated account or a hashtag. Step 3: Get to writing! Long story short: writing is difficult and it takes time! For a single blog post, I usually spend ~30 minutes planning (developing the idea and preparing an outline), 1-2 hours writing the draft, and another hour editing the post, finding a relevant image, and posting the material. Keep in mind the amount of time that writing a single blog post will take and plan your schedule accordingly. I dedicate a set time each week to drafting each post, generally with outlines and prep work on Monday night and draft writing on Tuesday, to keep me on schedule. Part of getting into the writing ‘zone’ involves figuring out your own process and establishing a rhythm. I like starting with an outline and some notes the day before I write the post because it helps take the pressure off of the day that I need to write the post in full. I’ve met people who prefer to do all of their writing in a single sitting. Try a few approaches to see what works best for you and then stick to a routine to help maintain your pace. Step 4: Hone your writing skills Even the best writers need good editors. Find a reliable friend, colleague, or family member who is willing to read and edit your posts. A good editor will not only read your post and find any grammatical mistakes, they will also take the time to think of more impactful ways to share your message. This is someone who helps you improve any awkward or unclear phrases and a person who provides feedback on a draft that you can immediately use and incorporate into the final version. Comments like “This is great!” or “I don’t like the conclusion” are not that helpful; comments such as “I like the short introduction” or “You can improve the conclusion by adding another citation” are things that can improve your writing. Ideally, you should also be confident in your editor so that you don’t have to spend time editing his/her edits. Step 5: Get inspired! Another challenge with maintaining a blog is finding inspiration for new posts. Inspiration will often come from unexpected places, like a dinnertime conversation with a friend or a flash of insight on your commute from work. Take notes of your ideas as they come…I’ve learned the hard way that it’s very easy to forget even the greatest ideas! To get inspired, stay on top of what other material is out there by following active bloggers and writers as well as recent science news. There is a lot of material online, but remember that your perspective will always be unique, and there is more than one way to look at a story. You might have a unique perspective as an early career researcher or from working on a topic at a level that most people might not recognize (like an anthropologist studying climate change). When thinking about stories that might be interesting for others, think about what you like to read about, either for your blog, your work, or just your personal interest: What topics do you care about? What inspires or interests you? What worries or concerns do you have related to science and technology? Chances are if it is something that fundamentally interests you, someone else would also love to read about it. Not feeling inspired? It happens to all of us! We all run into the occasional roadblock when it comes to writing. Check out our previous post on how to free yourself from writer’s block. When you are in a creative mood, make a list of post ideas and potential blog topics and keep these handy for when you get to a day when inspiration fails to strike. A science blogger’s life Starting (and, equally important, maintaining) a science blog can be a rewarding activity if you are ready to commit to the work required to make it happen. Even if you don’t feel that you are a ‘good’ writer, blogging can help you improve your written communication skills by helping you find your writing rhythm and keeping you on track with a post schedule. It’s also an opportunity to receive feedback from colleagues and readers and to share your perspectives with a new audience online. Once you’ve become an established blogger, you can also more broadly share your work using common hashtags, joining twitter conversations, and guest blogging. Whatever your professional interest or skill level may be, science blogging is a great place for aspiring science communicators who are enthusiastic to share the world of science with a new audience. Paraben levels in pregnant women’s urine correspond to cosmetic and personal care product use5/3/2017

A new study from Canada shows that preservatives commonly used in cosmetics, lotions, and shampoos can be found in the urine and breast milk of pregnant women.

The article, published in the April 4th issue of Environmental Science and Technology, looked at the relationship between how often pregnant women used personal care products and the levels of preservatives, specifically parabens, present in their urine and breast milk. The women in the study noted the cosmetics they used on a daily basis and researchers calculated if parabens levels were related to the number of personal care products used. Scientists from Health Canada, Brown University, Harvard University, and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute analyzed urine samples from 80 women from 2009-2010. All samples were collected during the second and third trimesters and breast milk samples were collected from 2-3 months post-partum. Women were asked to indicate the number and type of personal care products they used each day in a diary. Products were separated into categories such as deodorants, make-up, shampoos, conditioners, body lotions, hand soaps, and lip products. Four different types of parabens were measured by chemical analysis: butylparaben, methylparaben, n-propylparaben, and ethyl paraben. Parabens are used in cosmetics and other personal care products, including soaps and shampoos, as an anti-microbial preservative. Previous studies showed that parabens can be found in over 40% of rinse-off products (shampoos and conditioners, body wash, and face cleaners). Parabens are also found in leave-on cosmetics such as lotions and lipsticks, with methylparaben being the most abundant. Recent studies showed that some parabens can act as weak estrogen mimics. This finding, coupled with a 2004 study that found parabens in the breast tissues of women with breast cancer, raised concern about their ability to cause cancer. After scientific review, parabens are still considered safe for use in personal care products by the FDA, but certain types of parabens have been banned in the EU. The study showed that methylparaben was the most prevalent paraben in both urine and breast milk samples. Methylparaben levels in breast milk were 30 times lower than levels in urine samples. On average, the highest levels of parabens were found in urine samples collected during the morning hours (from 8am until noon) with the lowest levels seen in the evening (from 6pm to midnight). The researchers believe that this is due to women using more cosmetics and personal care products in the morning hours. Researchers also compared paraben levels in urine between women who used different amounts of personal care products. Women were classified as low users (0-5 products in a 24 hour period), medium users (6-9 products), or high users (10-14 products). When comparing different types of users, medium users had 21% higher levels of methylparaben in their urine when compared to low users, and high users had 161% more methylparaben than low users. The researchers also found much higher parabens levels when comparing women who did not report using a specific product versus those who did report using a product. For example, women who reported using lotion had 99% more methylparaben in their urine than women who did not use lotion. However, some products, such as oral care products, led to variable paraben levels that did not clearly show an increase with increased usage. This could be due to study participants forgetting to log certain items or differences in how the women used each product. Paraben levels measured in breast milk did not demonstrate a clear connection to personal care product use. Further analysis showed an increase in methylparaben levels in breast milk in women that reported using eye make-up. However, the magnitude of increase is small, strongly varies between study participants, and is found in only a small subset of the study group. Paraben levels in urine samples are lower than what was reported in other studies from the US, Spain, and Puerto Rico. This may be due to differences in the types and amounts of personal care product used among different socioeconomic groups. Other studies also found that women are more likely to have higher urinary paraben levels than men, which the researchers believe is due to women using more personal care products. Parabens are 10,000 times less potent than natural estrogen. Parabens are also far less estrogenic than natural phytoestrogens like daidzein, which is found in soy. Epidemiologists have yet to find any associated cancer risks linked to phytoestrogen consumption, so the chance that an estrogen as weak as parabens will cause harm is extremely unlikely. Critics of the 2004 breast cancer study which reported that parabens were present in breast cancer tissue point out several flaws with the findings. Researchers did not measure paraben levels in non-cancerous tissues, making it impossible to assign any blame to parabens in causing breast cancer. Parabens also have a very short half-life, which means that these chemicals do not remain in the body for very long and are rapidly excreted. Concerns about paraben safety led many cosmetics companies and consumers to seek out paraben-free alternatives. Regulators are still working to ensure that parabens are safe for consumer use but the data available now seem to point to parabens being of little concern.

Are you up to the challenge?

If you’ve seen any advertisements for martial arts schools, you’ve likely noticed how the various forms of martial arts are all touted as ways for a person to gain self-confidence and self-esteem. Given the fact that I already have a black belt and am now approximately one year away from earning a second, you would think that confidence would be no problem, that I’ve already gained perfect self-esteem from earning a black belt. How could I ever lack confidence? After nearly three years of tae kwon do training in Liverpool, I now have a new club and a new coach. Stepping into an unknown dojo where the warm-ups, stretches, and drills are all new is a humbling experience when you get to a moment where you feel like you can’t keep up with everyone who knows the routine already. It’s left me feeling less confident in my abilities than the month before and more frustrated when I got things wrong. Even with three years of training and a red belt, I still suffer from waivers in my own self-confidence in the sport. There are many experiences as a PhD student or early career researcher that can cause our confidence to waiver: a rejected grant, a scathing comment on a manuscript review, or a failed experiment. We all face challenging moments that shake our beliefs in our own value or skills. Having strong self-confidence is one of the ways that we can work through challenging moments as we keep our head held high and our mind in a positive place. In this week’s post we’ll discuss the importance of self-confidence and the steps you can take to unveil your own inner champion. The basics of confidence Confidence is touted as one of these all-important facets of life, as something that we all need to have. But does anyone really know how to get it? Is it learned or inherited? How does one learn to be confident? Similar to the concept of networking, confidence is a nebulous concept that feels difficult to acquire. The Oxford dictionary lists the first definition of confidence as: “The feeling or belief that one can have faith in or rely on someone or something.” For this post, we’re more interested in the secondary definition: “A feeling of self-assurance arising from an appreciation of one's own abilities or qualities.” In other words, confidence is the resounding voice in your head that tells you “I can do this” and when you hear that voice, you believe it. But let’s approach this more scientifically. We shouldn’t believe that voice without empirical evidence—we need proof of our own abilities, not just belief in them. Thankfully in academic research, empirical metrics are everywhere. It’s why we care about endpoints like the number of papers we published, how many citations those papers have, who comes to our talks, how many grants/awards we receive, etc. We put value on our tangible accomplishments, all listed out conveniently on our CV. So if they’re all listed out and we can count them and read them, it should be easy to gain confidence from them, right? This is only true if we appreciate our achievements, our abilities, and who we are as people and as researchers. We can have a CV filled with papers, book chapters, and awards yet can still feel like we are not good enough. This is evident when talking about imposter syndrome, a situation where regardless of the number of achievements or accolades, you discredit yourself and your work entirely. The trick is that confidence cannot be imparted on you externally—no number of papers or awards will make you more confident. Confidence has to come from within. How do you gain confidence? Building confidence cannot done in a single day of soul-searching, but it’s something that you have to work on continually. Confidence is also ephemeral; it can wash over you and make you feel as if you’re invincible, or it can quickly recede and leave you feeling vulnerable, just like I experience in own waivers of confidence associated with tae kwon do. Martial arts emphasize the importance of the mental components of the sport, such as meditation, courtesy, and respect, at the same time as teaching you physical skills. But the key to finding confidence in a sport, or any activity, and even in your own career, is you. Anytime I go to a tournament or test for a new belt, I get nervous. I see the other people I will fight against or the high-ranking black belts who will judge my performance. It’s not enough to look down at my red belt and see my achievements with my own eyes—I have to feel them, too. Your own path to self-confidence will be very personal, but if you’re looking to make steps in a positive direction, here are some ways that you can work towards breaking down the barrier between seeing and believing in yourself: Find your passion. In your own career, you will find that a love of science or research doesn’t necessarily translate into a passion for every aspect of the job. You also won’t be naturally gifted at every part of your work. To help build confidence in the early stages of your career, find and focus on the part of your work that you love the most and use this as a central focus of your confidence-building activities. For me this focus was (and still is) writing. I used writing as a way to gain confidence in the rest of my project. It was a way for me to collate thoughts and ideas before taking them to a place where I had less confidence, like a platform presentation or a committee meeting. Writing helped me realize that I did know what I was talking about and gave me an opportunity to do something I liked while also improving on the other parts of my work, like public speaking. Keep your level of confidence steady through both ups and downs. Although your confidence will inevitably shift when faced with the positive and negative events of your situation or career path, work to avoid the extreme ends of the spectrum (either a complete lack of confidence or over-inflated self-worth) by finding your center ground. From this position, you can use positive situations to propel you further, but be sure to stay within reasonable bounds. One published paper won’t lead to a Nobel prize, but it is a worthwhile achievement and worthy of celebration. On the other hand, one rejected paper is not a complete step down from your center ground, but rather a chance to take the positive part of a negative situation and to learn from what went wrong the first time. Failures are one of the best ways we can gain fresh perspectives and to improve our work for the next submission. Practice positive thinking. In science we are surrounded by critiques and reviews of our work, and many of us will internalize these messages as well as adding a few negative ones of our own. Being self-assured in your own qualities and abilities involves injecting optimism into your internal dialogue to help offset the critiques that come with a high-achieving career. Positive thinking doesn’t have to be cheesy or fake, and you don’t need a pair of pompoms to be your own cheerleader. For example, positive thinking can provide a positive spin to negative situations (“The rejection was pretty tough, but the reviewer makes good points that I can incorporate into the next draft”) or can help you envision a positive outcome instead of dwelling on a negative one (“I’m nervous for the talk, but I’ve practiced it enough now that I know I’ll do a great job once I get on the stage!”). I am not a naturally optimistic person, especially when I get nervous. One approach that I use is to change the situation when I’m surrounded by my own negative thoughts. I text a friend or call my husband to vent my nerves to someone else or to simply change the topic. Even turning on some upbeat music can help shift your mindset when you find yourself in a funk. If I am nervous for a talk, a meeting, or a tournament, I turn on some Sia or Madonna to put my mind in a better place. Shifting your situation can help improve your mood and broaden your perspective, opening up your mind to positive thoughts instead of negative ones. Remember that failing doesn’t mean you’re a failure. Failing is an essential part of any career and is also a facet of becoming an expert in any sport, skill, trade, or activity. Unless you are a prodigy, trying something new or beyond your current skill level will involve various degrees of failure. Becoming self-confident means facing a potential failure with cautious optimism: cautious in that you know you need to try your best, but optimistic in that you believe you can succeed, even if you fail the first time around. Another important thing to remember is that coaches and mentors give critiques specifically because they want to see you improve. In general, people who seek out careers as professor want to see their students and their mentees succeed. Your mentors know that you are the next generation of scientists, and their critiques are there to help you, even if they are offered in a rather blunt or direct manner. You should also recognize that when people criticize your work, they are critiquing your output, not you as a person. Becoming unstoppable Confidence is not an easy thing to obtain. The keys to building confidence are to stay grounded, explore new skills and tasks while highlighting on your passions and abilities, and work to maintain a positive outlook. When good things happen, maintain a steady disposition and find productive ways to cope with failure, even if it means a short change of perspective or distraction from the situation. Once you begin living life with confidence, it will be difficult for any challenge to dislodge you completely. You’ll find that the challenges don’t last forever and the critiques only serve to fuel your internal flame.

What are microplastics?

The term “microplastics” refers to plastic and polymer debris with a diameter ranging from one micrometer up to five millimeters. This range of sizes includes debris that is smaller than the width of a human hair up to pieces that are as large as a pebble. Microplastics can form when larger plastic waste, such as drink bottles, break down into smaller chunks. Another source of microplastics are ‘microbeads’, or small pieces of plastic that are sometimes added to personal care products. Certain brands of exfoliating face cleansers or toothpaste have microbeads in them. How do they get into the environment? While personal care products are one source of microplastics, their use in cosmetic products is starting to be phased out. Microbeads are now banned in products made in the US and the UK is committed to implementing a ban by October 2017. There is currently no ban in the EU but the trade body Cosmetics Europe is encouraging its members to phase out microbeads by 2020. The primary source of microplastics in the environment comes from the physical break-down of plastic waste. The amount of plastic generated each year has increased by a factor of four from 2004 to 2014, and it is predicted that by 2050 we could be making up to 33 billion tons of plastic per year. Because many of these plastic products are for short-term use, like product packing materials or single-use packaging, a large amount of plastic will be disposed of shortly after use. Plastic is so used because of its durability. Larger pieces of plastic such as bottles and containers break down into smaller pieces, but these small pieces never truly degrade. Unless plastic waste is incinerated, it will continue to cycle through the environment. Because of this, microplastics and plastic litter can be found in a wide range of places: parks, prairies, forests, rivers, lakes, estuaries, coastal areas, the open ocean, and even deep sea sediments. Why are scientists concerned? Once microplastics enter the environment, plastics are eaten by animals, especially fish and birds. Recent studies showed that up to 90% of all seabirds have eaten plastic, and plastic could even be found in over half of the world’s sea turtle population. Many plastic pieces can simply be ejected from the body as waste, but too much plastic can cause serious harm to animals. Larger microplastic pieces can cause physical damage to an animal, such as internal cuts and bleeding, inflammation, and lower energy levels from consuming too much inedible and indigestible material. The smallest pieces of microplastic will be eaten by animals such as diatoms, copepods, and brine shrimp, while larger pieces are consumed by shellfish, starfish, crabs, and fish such as catfish, perch, and trout. Smaller pieces eaten by animals lower on the food chain can then build up over time as these animals are eaten by larger predator species, causing microplastics to remain and even increase over time through the food chain. An additional concern with animals eating microplastics comes from the chemical additives included in many plastic products that can be toxic. Certain chemicals are added to plastics for increased elasticity or rigidity, including bisphenol A, phthalates, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and metals. Unlike the plastic polymers these chemicals are added to, additives are not as stable and can break apart from the plastics. Even if a fish or a mussel is unharmed by eating small pieces of plastic, the toxic chemicals attached to the plastic can get into the animal and cause serious toxic damage. Should I be concerned? Because plastics are so widespread in the environment and are known to be consumed by a large number of animals, scientists worry that traces of microplastics can be found in humans. This field of research is still growing, however, and there haven’t yet been any large-scale studies. Scientists are interested in looking at microplastic levels in humans and determining if differences in seafood consumption correspond with microplastic levels in the body. But because this field is still new, there is a lot we still don’t know about microplastics. Many of the uncertainties are around the exact amount of microplastics that fish (and humans) might eat. This uncertainty comes from the fact that it is difficult to quantify the amount of plastic when there is such a broad range of sizes and shapes. Microplastics also represent a wide range of materials, all of which have different added chemicals, making it more of a challenge to determine what, exactly, we could be potentially exposed to. Research progress is being made across the world to help answer these questions. A recent review highlighted the results of over 80 studies in aquatic environments which looked at both the distribution of plastic waste and the impacts of microplastics on animals and plants. The authors also identified ‘hot spots’ of microplastic pollution across the world. Other questions that scientists are working to answer will help policymakers determine the best course of action on national and international levels. These questions include how microplastics move in the environment, what types of polymers are the most common, and how ecosystems as a whole are affected by microplastics. What can I do? Using less plastic is a small yet simple start towards solving part of the problem. If you live in a country that does not ban microbeads in cosmetics, see if your current personal care products have added microplastics—and if they do, explore alternative products instead. Local recycling and plastic reduction efforts have also been effective at decreasing plastic waste. In San Jose, CA, a 2012 plastic bag ban reduced the amount of plastic waste in the city by up to 89%. Keep a reusable bag with you while shopping and promote similar shopping initiatives in your own community. If you want to become proactive in plastic waste reduction efforts in the US, NOAA maintains a list of clean-up events, teaching guides, and resources for recreational users as part of its Marine Debris program. NOAA is also the government organization in charge of awarding research grands, education, and clean-up efforts around microplastics and marine debris—so let your congressional representatives know that you support NOAA and don’t want their efforts to be hindered by budget cuts or government scientist gag orders.

“So, what are your plans for after you finish?”

It’s no secret that being a PhD student is stressful. Thankfully the process of earning a PhD doesn’t last forever, but because of its finite nature, any conversations with friends or colleagues will lead to the inevitable question of “So, what’s next?.” My group of colleagues includes some final year PhD students, all of whom are facing a not-too-distant future of writing and defending their dissertations. On top of this pressure, they are also worried about their job prospects and transition from student to employee. When I finished my PhD, I was fortunate enough to have a prospective post-doc offer not long after finishing my dissertation. I managed to pass the time between submitting my dissertation and graduation without any additional job search stress. But I didn’t escape the job search stress for very long—last spring, and after many months of uncertainty about extending my post-doc contract, I found myself scrambling for what to do next. I applied for 9 jobs, and even landed an interview for one of them, but nothing fruitful came out of my search. I took a deep breath of relief when my contract was officially extended, but the experience left me with two realizations: 1) I was very lucky to still have a job, and 2) I would be in the exact same position again in 10 months’ time if I didn’t do something differently. The importance of a professional network Part of the reason for my struggle during my initial job search was that I only sort of knew what I wanted to do, which at the time included anything related to science communication, publications, public engagement, and so on. I knew that I didn’t want a career as a researcher, but I didn’t know what my exact options were or how to get there. What would an application reviewer be looking for on my resume? What sorts of skills did I need to highlight that were not on my academic CV? What types of positions could I realistically aim for with my skills and experience? I had a lack of understanding since I had only recently decided what I wanted to do after my research post, and because I was new to the area I also lacked an existing network of colleagues and potential mentors working in the field that I wanted to enter. From my time as a researcher, I had a vast network of academics as well as industry and government researchers, but I didn’t know anyone doing science communication or writing. I had a broad understanding of where I wanted to go, but I was walking there blindfolded. We discussed in a previous post about the nebulous nature of networking and some approaches you can use to make connections. Before we go further in this post, it would be good to revisit the definition of a network once more. Simply put, your network is the set of connections you have to colleagues, friends, and family members. These are connections you’ve made on a personal level: it’s not just shaking someone’s hand at a conference but means having a working relationship with them. They know who you are, what you can do, and your passions and area of expertise. Networking may not seem that important if you are in the midst of lab work or writing your dissertation. But a solid network with more than one branch can take you places that wouldn’t be possible by simply sending in job applications and hoping for the best. Networking can show you hidden opportunities that won’t always be advertised and your mentors and connections can help you figure out how to enter into a new area by helping you to highlight your relevant skills or lay out a job-specific resume. But there’s a trick to networking: because your network represents your relationships with other people, it’s not something you can put together on a short notice. You need to establish your network early on in your career so you have time to work with and establish trust between you and your connections. The key is to build trust with others before you need something from the other person—like a job, for example. Where should I start? 1) Identify your skills, professional interests, and your long-term career goals After going through contract extension panic, I realized that I wanted to pursue a career in science communication. But my short stint of job applications made me realize that this was a very broad ambition, and I felt like I was spreading myself very thin trying to cover every aspect of what this type of career could entail. One of the ways I narrowed my career target was by reading Born for This and going through the book’s exercises. Perhaps the most powerful exercise in the book was when the author told us to think about what other people ask us to help with the most. This is a way of showing us what we’re good at because it’s something that others ask us to do for them. I realized that over the course of my time as both a PhD student and post-doc, I helped others the most with writing. Sometimes it was reviewing articles or manuscripts, other times it was in taking the lead on a paper that had been sitting unwritten for too many months. This exercise helped me realize something that was both a passion and a skill, which then helped me focus on careers related to writing. 2) Rework your brand Knowing that I wanted to look for writing jobs, I sought out more opportunities to write. I participated in writing contests and guest posts for blogs and University websites. I then restructured my CV to highlight my written work more strongly. I also took part in writing classes (Coursera has some fantastic online courses if you’re looking for something free) and made sure that my social media profiles were up-to-date and reflected my career goals. It sounds like a lot of work, and I did spend a good deal of time working on this outside of my normal post-doc hours. But it was also very enjoyable—I enjoyed learning about new topics and I got to meet other like-minded people in the process. This should also be a part of your re-branding process; if you’re not having a good time being the person you’re working hard to become, you should reconsider the path you’re walking on. 3) Look for opportunities that fit your style and your needs Once you have your career goal and your brand figured out, start looking for what options you have based on your current/future limitations. For me, I knew that my husband had a job offer in Manchester for two years, so I wanted to look for science writing/communication jobs in that area. While looking at jobs on LinkedIn I found several posts for medical writers, and there were a lot of entry-level positions in the Manchester area. I soon discovered a field, of which I had never heard, that was looking for PhD-trained researchers right in my back yard! I followed up by looking in more detail at the job advertisements, finding some resources about the field online, and sent off my resume for a couple of posts even though I didn’t need a job at the time. I felt that I had struck gold, but knew that it would take more than a good looking CV to get me my first job in a new area. 4) Look for connections that can help you reach those opportunities Last autumn I was busy trying to get lab work finished so I could make more progress on the final manuscript for my project. One afternoon I found myself chatting with a PI in the physiology department whose lab space I used for some of my experiments. He knew that I was getting towards the end of my post-doc contract and asked if I had plans to stay in research and I told him I was looking to make a transition into the medical communications industry. As it turned out, the PI had a friend who was working at a medical writing firm near Manchester. He offered to pass me along his contact details and even to put in a good word with me at the pub when he met his friend for a drink later that week. This conversation was a lucky exchange but one that highlights the importance of having trusted connections in all parts of your work. I was only working in this lab part-time and had no interest in continuing that facet of my work, but the PI knew I was hard-working, organized, and creative. He soon passed along his friend’s contact details and I made the all-important initial contact: a request for an informational interview. I didn’t ask this new contact for a job or to look at my CV, since at the time he was only a colleague of a colleague. In my initial exchange I asked if we could meet informally to discuss more about medical communications in general. My goal was to meet someone in the field and hear from them what the work was like, then later on to expand this relationship and work towards getting help structuring my CV or even hints on potential job posts. This was all starting to happen close to six months before my contract would finished, so I also didn’t need anything explicit during our initial contact. PS: If you’re looking for tips on what to ask during an information interview, be sure to check out Alaina Levine’s “Networking for Nerds book-it’s a great read! 5) Pursue opportunities as they come The informational interview that I proposed never actually happened. As it turned out, the company was recruiting for an associate medical writer, and my new contact asked for my CV right away. I was nervous to send off my CV, but the work I had done restructuring my resume and highlighting my writing-oriented skills paid off. I was then given a writing test and made sure to not take the effort lightly even though I didn’t need a job at that time. I learned more about what was expected and dedicated a set amount of time to working on the test. One successful writing test and one in-person interview later (with my new contact at the other side of the table), I found myself celebrating the new year with a job offer to my name—months ahead of schedule! Writing your own career story My own career story was the result of yet another stroke of luck. But sometimes luck isn’t just a random coincidence: luck is something you can make for yourself. Sometimes luck is a product of the time and place you’re in. Sometimes luck is an opportunity you didn’t plan for that ends up directing your life’s story. Luck, timing, and the ability to find and seize opportunities leads us to many paths in our careers, and it’s often on these unplanned roads that we find the way through our own career journey. But in order to take advantage of the hidden opportunities that can lead to game-changing moments, we need to network. This involves having strong personal connections with a wide range of colleagues as well as a solid and trusted reputation that connects to your name. Networking might seem like something nebulous or far-off while you’re knee deep in your own research, but thinking about your own career path as well as what connections you need to get there can take away part of the stress and uncertainty of your job search. You might not instantly have an answer for the question “So, what are you doing after you graduate?” but at least you’ll be able to say with confidence: “I’m exploring my options.”

This week on the Tox City Tribune, we’re offering an open letter that you can amend and send to your state’s congressional representatives. This week we are tackling a bill proposed in the House of Representatives: H.R.861-To terminate the Environmental Protection Agency. We wrote this letter as a way to talk directly to members of the current US Congress about the dangers of blindly rolling back legislation that could seriously harm environmental health and could also lead to severe impacts on our own health.

At the end of the letter we’ve provided links and resources where you can find relevant local information about the EPA’s work in the state where you live. This letter can be amended and sent to any of your local representatives, not just the ones who have sponsored or co-sponsored this bill (which currently includes Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, Rep. Steven Palazzo of Mississippi, and Rep. Barry Loudermilk of Georgia). We hope that this open letter can help voice the concerns for Americans who do not take attacks on the USEPA lightly. We also hope that this type of engagement can provide a new perspective about the importance of environmental protection to the conservative representatives who seem to doubt its usefulness. If you have questions, please get in touch! ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Dear Rep. Matt Gaetz, My name is Erica Brockmeier and I am a Florida voter who is passionate about our beautiful state. I earned my PhD in Toxicology from the University of Florida in December 2013. My project was supported by a graduate research fellowship from the US EPA and focused on the impacts of paper mill effluents on local fish populations in the Florida panhandle. Part of my dissertation focused on Florida’s ecosystems was published and is available to read through open access. It’s my love of Florida and my concern for its unique and fragile ecosystems that motivates my letter to you. I am concerned with H.R.861 because of what this bill will mean for environmental and human health and for the landscapes and resources that make our country and our state wonderful places to live. Our country is a vastly different place than it was in 1970 when the EPA was first enacted by President Nixon. Toxic pesticides like DDT were sprayed without thought of consequence, our gasoline was filled with lead, and the Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so polluted that it actually caught on fire (you can read more stories and see pictures here. Thanks to a government administration that recognized the importance of protecting environmental (and subsequently human) health, the US EPA was established to consolidate efforts to research, monitor, and establish rules for the safe use and disposal of chemicals. The US EPA is also in charge of developing long-term clean-up plans for polluted sites as part of the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). In Florida there are 52 Superfund sites, 4 of them located in Escambia county*. The US EPA is responsible for managing the cleanup of these sites and works to make them usable and safe for residents, visitors, and local wildlife. There has been a lot of political discussion about the pitfalls of over-regulation while forgetting the economic benefits of many of these laws. Government regulations managed by the US EPA such as the Clean Air Act directly enhance our country’s economic well-being through an increased numbers of jobs in the engineering, construction, and manufacturing sectors. All of these benefits come at very low cost to the industries they are regulating. For example, data from 2005 showed that less than 1% of the revenue generated by US manufacturers was required for pollution control. Environmental regulations also protect Americans and the places that make our country truly great. The US EPA estimated that amendments made to the clean air act in 1990 saved over 160,000 lives and prevented 86,000 emergency room visits in 2010 alone. The US EPA was also present during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill and helped gulf coast areas by collecting emergency data and ensuring sure that beaches and waters were safe for wildlife. The EPA’s efforts were also crucial for ensuring that clean-up efforts after the spill made Florida beaches ready to be enjoyed by the 20 million Florida residents and the 90 million tourists who visit our state every year.* While it is important for our government to work towards decreasing unnecessary legislations and government bureaucracy, casting aside the efforts of an entire federal agency will put the lives and health of American people at risk by opening up our environment to inexcusable damage. Nearly 50 years ago our government, led by a Republican president, had the foresight to recognize the importance of a clean environment for the American people. Our founding fathers also established our country on the foundations of basic human rights including “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” The first of these rights is life. The right to live as an American citizen also includes the right to live life to the fullest: breathing clean air, drinking safe water, and protecting our country’s natural resources for future generations of Americans. Part of living the American Dream also involves the opportunity to enjoy the incredible natural places that make our nation truly great, especially our incredible national parks and the landscapes and ecosystems that existed since before we were a unified nation. These great American places need as much protection as the American people. And protecting them, as well as ourselves, is a rewarding legacy we can leave for future generations, and justifies the EPA’s existence. Our founding fathers and the founders of the EPA shared a common vision that provides the opportunity for a life well-lived for every American. Clean air, drinkable water, and protection from harmful chemicals enable us all to achieve this American dream. The problems that we’ll face as a nation in the next 50 years will be more challenging than when the EPA was first brought to life. The issues will not be as obvious as rivers on fire or skies full of smog but can come from chemicals that haven’t been produced yet, or by future contaminations and spills incidents that go undetected, such as the contamination of drinking water in Flint, Michigan last year. Because our country still has a long ways to go for ensuring that our land is safe and clean for everyone, I would encourage you to remove your support from H.R.861 and re-focus your efforts on something that would provide more benefit to the American people. The US EPA is fundamental for ensuring that Americans have the right to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, and throwing away this agency would do a significant disservice to the rights and well-being of all American citizens. I would also encourage you and your fellow representatives to support an EPA budget that works for supporting the health of the American people. Recent news articles state that proposed budget cuts from the current administration to the EPA are up to 40% of the current budget. Because of this Agency’s crucial importance in protecting environmental quality, any broad budget cuts that are not thoroughly evaluated have the potential to damage our country and the health of the American people significantly. As one of the cuts is potentially for the program which supported my graduate education, I would also like to vouch personally for the benefits of these types of EPA programs. I would not be in the position I am today without the financial support from the EPA STAR program. I am thankful to be part of such a beautiful state in the USA, and I hope that my fellow citizens can continue to enjoy the beautiful landscapes, pristine ecosystems, and enriching environments that attract so many visitors to our state every year. Sincerely, Erica K. Brockmeier, Ph.D. Text notes: Italicized opening paragraph: Please replace with your own personal background, including why you feel that protecting environmental health is important. Insert 1: For information on superfund sites in your state/local area, please visit this website. Insert 2: If you know of a recent or historical environmental disaster in your area, include a brief description of the incident here. If you aren’t sure where to start, you can click here. Italicized pentultimate paragraph: Please replace with a personal connection you might have to an EPA program, office, activity, etc, or simply a reason why you feel that environmental health should be a priority for our government representatives.

Last week I attended a seminar about new advances in clinical trials for cancer treatments. The seminar started off with one of the research leads from the University of Liverpool clinical trials research center introducing the topic and the upcoming speakers. The introduction emphasized the importance of research with impact and that knowledge for the sake of knowledge alone isn’t useful. Based on the number of problems that scientific research is needed to solve, the organizer reasoned, we simply can’t do research that doesn’t have a direct application.

I didn’t fully disagree with the cancer research group lead, but his statement did catch me off-guard. There’s certainly a lot of research that seems to go nowhere or that leaves us asking “Why did tax money go to this study?” Having a vision of what the research can lead to is a way to ensure that the work we do as researchers has meaning. But at the same time, it’s unfair to say that knowledge for the sake of knowledge isn’t necessarily useful. This also presents a challenge for science communication, since one of the ways that we engage with an audience is to try to connect them to a story by sharing its impact. The lack of an immediate impact is not necessarily a failure of science, but it is a potential barrier for effective science communication. Not everything that scientists do will be relevant, interesting, or meaningful for the everyday person—but does that mean we can’t communicate this kind of science effectively? The comments made at the seminar came at a time when I was halfway through reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I found myself deeply intrigued by Robert Pirsig’s discussion on the infinite nature of hypothesis testing. Will science inevitably continue to answer one hypothesis at a time only to have five more hypotheses appear once that one has been addressed? Will we ever have data that’s solid enough to support or refute a hypothesis, or will there always be an infinite number of counter-explanations for a given observation? Pirsig’s book wasn’t what exactly light evening reading, and maybe not the way to get people interested in science, but I did enjoy his discussions and spend some time pondering both his book and one of my previous posts on the philosophical foundation of scientific research. PhD students and early career researchers know all too well how new results often lead us to more burning questions as opposed to solid answers. As scientists, we slowly work towards conclusions about how the world works and gain, piece-by-piece, a better understanding of our world. But the progress of science isn’t always as tedious as it may feel when we’re in the middle of it. My own enthusiasm for science was ignited last week with the news from NASA about the TRAPPIST-1 system. And with global threats like climate change, freak asteroids, and American politics, it seems like a good time to get excited about potentially habitable planets that are 40 light years away! NASA news is broadly exciting for many of us, but it’s also the type of news that reflects this idea that not all science will impact our day-to-day lives. This work is science for the sake of science, for a better understanding of our universe, and quite unlikely to directly affect anyone in this lifetime. It’s the kind of story that makes for great science news, but doesn’t necessarily answer the question of “Why should I care about science?” for people who are living their own lives and who aren’t necessarily interested in the mysteries of the universe. Two weeks ago I talked about the upcoming March for Science and the goal of getting people on the side of science. While engagement is essential for the future of science, we should also recognize that not everyone will be as enthusiastic about science as we are. A recent survey from voters in the 2016 election asked people what they consider “very important” for their voting decisions. While the economy and terrorism are broadly important to most voters, only 52% of voters surveyed considered the environment influential in their voting decision. It sounds like an uphill battle at first, but with these things in mind we can come up with a strategy for the future of science communication: - Part of our message needs to reflect science as a methodology, not just a field of study. To improve science literacy, we can’t simply report more scientific discoveries but should instead emphasize the scientific discovery and hypothesis validation process. - We should write science communication stories as if we were journalists and not public relations officers. Journalists write stories that discuss a topic from as many sides as possible. If you’re promoting science as a means of reaching a universal truth, you should present the story in a way that allows people to draw their own conclusions or alternative hypothesis about a topic’s worth. - We should not be shy about the fact that not all research will be directly relevant for people’s lives. We can emphasize that scientists may need to ask “How does this work?” while holding back on the inevitable question of “Why should I care?” right away. - Scientists and science communicators can also think about how they can meet people where they are. As an example, an EPA scientist from Louisiana recently attended a town hall meeting, where her statements were met with enthusiastic support. People who are already interested in science might meet us on twitter, come to our seminars, or meet us at a museum, but what about people who might not have a weekend trip to the Natural history museum on the top of their to do list? You can also think about what science stories you connect with: Do you like all fields of science? What drives your interest in a topic? Why do you click on a news headline? There are numerous topics in science and research that are relevant for people who aren’t scientists, ranging from cancer drug trials to global warming. The stories we tell about these topics will make their strongest impacts when they are focused on the impacts to people over the science itself. But as scientists, we shouldn’t neglect the utility of knowledge for the sake of knowledge or consider people as scientifically illiterate/unengaged just because they don’t share the same curiosities as we do. Part of the goal of science communication can be in sharing science for what it is: as a way of reaching the truth that can be slow, monotonous, and mysterious—but it’s a way that we can reach incredible findings that have impact beyond our own lives. As the saying goes: sometimes the journey is more important than the destination.

A new field study reports a decrease in the number of abnormal intersex fish living downstream of Kitchener, Ontario after effluent processing changes were made at the town’s wastewater treatment plant.

The article, published in the February 7th issue of Environmental Science and Technology, show how changes made at the Kitchener wastewater treatment plant lowered the number of rainbow darter with reproductive abnormalities. The plant upgrade included the addition of a nitrifying procedure, which reduced the effluent’s estrogen levels. Researchers from the University of Waterloo, the Ontario Ministry of Climate Change, and Environment Canada collected fish from the Grand River both before and after processing changes. Fish were also collected from a clean upstream site and from a site downstream of another wastewater treatment plant. This plant in Waterloo did not undergo any processing changes. Intersex fish have the reproductive tissues of both males and females. In male fish, intersex is measured as the number of egg cells in the testes. Intersex fish were first discovered in 2003 by USGS researchers in West Virginia. More studies have since found large numbers of intersex fish across North America. Exposure to hormones such as natural and synthetic estrogen is thought to be the culprit for these intersex characteristics. This study looked for the presence of intersex in a small freshwater fish species, the rainbow darter, from 2007 through 2015. Effluent processing changes were made in mid-2012. Darters collected from the clean site had low numbers of intersex (less than 20%) and the levels did not change during the study. Downstream of the Kitchener plant, as many as 100% of fish sampled were intersex before 2012. The level of intersex in these fish dropped by more than 75% by the end of 2015. The number of intersex fish was consistent at the site where there were no effluent processing changes. The estrogen levels were measured before and after plant upgrades. Estrogen levels in the Kitchener wastewater treatment plant decreased after 2012. There were also lower levels of pharmaceuticals, including ibuprofen, naproxen, and carbamazepine. Estrogen exposure isn’t limited to intersex in fish. A lake-wide study found that estrogen exposure could wipe out entire fish populations. Male fish exposed to estrogens also have lower testosterone levels and smaller testes. Treatment changes made at the Kitchener plant included nitrification of the activated sludge. This involves adding bacteria that convert ammonia to nitrogen. Previous studies showed that nitrification of sludge could reduce the amount of hormones in effluents, but this is the first study to show positive impacts on fish populations. Since rainbow darter can live up to five years, the population’s recovery over the three year period shows that intersex is not permanent. One confounding result from this study is the increase in effluent nitrogen levels. While ammonia, pharmaceuticals, and estrogen levels decreased, nitrates increased to 20 mg/L. The EPA recommends that nitrate levels in drinking water be no higher than 10 mg/L. Higher nitrogen levels promote algae overgrowth that can lead to decreases in oxygen, a process known as eutrophication. Future work at this site will need to ensure that nitrogen levels are not causing other types of environmental damage.

Every time I opened Google News last month, I hesitated with bated breath before scrolling down to the ‘Science’ section. I found myself too nervous to read whatever shocking policy changes would be waiting for me there. Even a month after the inauguration, I and many other scientists continue to wonder what the next four years will have in store. Everything related to science in the US, from basic research funding to environmental policy changes, feels like it’s at the cusp of challenging days ahead.

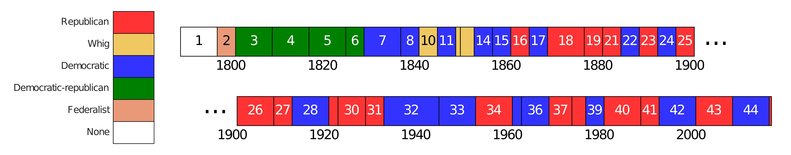

I empathize with the scientists who are silenced and for my friends and colleagues who work at government institutions, wondering how their jobs will be affected. I cheer on the rogue twitter accounts (my personal favorite being the tongue-in-cheek @MordorNPS) and I started preparing letters to the members of congress who are proposing bills that would damage the integrity of environmental regulations. But despite my empathy with the plight of government researchers and concerns for what an “alternative facts” administration will do over the next four years, I am hesitant to fully support the concept of a March for Science. I am concerned that the march will further polarize the dialogue at the interface of science and politics instead of harmonizing science communication and public outreach. In the US, scientists are overwhelmingly liberal, with 55% identifying as Democratic, 32% Independent, and only 6% as Republican. In contrast, scientific literacy, or illiteracy, is less partisan—and it’s incorrect to label one party as ‘anti-science’ over another. Scientists may tend to picture concepts such as not believing in global warming or evolution as primarily conservative viewpoints. But while 50% of conservatives surveyed said that they thought the earth was only 10,000 years old, so did 33% of liberals. Recent concerns about how Trump’s comments could potentially fuel the anti-vaccine movement didn’t mention the fact that a higher percentage of Democrats believe that vaccines are not safe. While there are extremely vocal Conservative opponents of ideas like climate change and evolution, there is a general understanding and support for the science underpinning climate change among representatives of the Republican Party. Recent news articles have highlighted bills put forth by freshmen Republican representatives to disband the US EPA, but at the same time other Republicans are working on a national carbon tax to address climate change. This effort is supported by senior Republicans who said that the “mounting evidence of climate change is growing too strong to ignore”. The difference between the two parties is not necessarily a belief in the science but in how that information is used to shape policies, and Republicans will generally advocate for less restrictive and more open market policies to approach these problems. Yes, there are vocal opponents of climate change science, and yes, the current administration has already done numerous things to warrant mistrust from scientists—but to seemingly discredit an entire party holding a majority position of the federal legislature is not a recipe for making progress. If the March for Science is going to make strides in its goal of sharing clear, non-partisan messages, it will take more than a single act of demonstration against the current administration. Looking beyond this current administration, it’s not a solid long-term strategy for scientists to be primarily aligned with only one side of the political spectrum. In American politics, one party is never in power for long, and the office of the President tends to alternate back and forth between red and blue (and the same trend follows for the House and Senate). This pendulum swing is the natural ebb and flow of political leanings in America, and makes Trump’s election win look like it was somewhat inevitable. Scientists can envision a Democratic presidential victory in 2020 as a stepping stone for progress in science. But what about future elections, from 2024 and beyond? Given the number of problems that need solid scientific solutions, from climate change to antibiotic resistance to a comet crashing into planet earth, can scientists afford to only rely on 4-8 year cycles? In our post two weeks ago, we discussed the role that Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring had in bringing about significant changes and improvements to environmental protection in the US during the 1960’s. In response to this movement and to help mediate the laws that were being drawn up by separate states and cities, Republican President Richard Nixon founded the US EPA in 1970. The US EPA continues to set national guidelines as well as monitors and enforces those laws, such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. While Nixon won’t go down as one of America’s most popular presidents, his actions and those of other Republicans in power demonstrate that the GOP is historically not an anti-science group. President Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in setting up the US Food and Drug Administration, set up five National Parks and numerous National monuments, and went on a few scientific explorations of his own. Senator Barry Goldwater, also a republican, was an advocate for environmental protection efforts in the 1960’s, saying: While I am a great believer in the free competitive enterprise system and all that it entails, I am an even stronger believer in the right of our people to live in a clean and pollution-free environment. To this end, it is my belief that when pollution is found, it should be halted at the source, even if this requires stringent government action against important segments of our national economy.” Science is not inherently bipartisan, but scientists, and the issues that they tackle, do have political biases. A danger of a politically-charged event like the March for Science is that it may undermine the public’s perception of a scientist as being a politically unbiased person. The way in which we choose to stand up for our work as scientists has to go beyond the March for Science. It requires us to develop a clear message of how science can provide support or guidance on the policies our representatives adopt on. Regardless of who is in charge, scientists should always advocate the utility of science and to help enable government policies founded on science, not on political biases. After the march, scientists can work towards this objective by sharing their thoughts and concerns directly with legislators. We should support our representatives who are working on legislation to support clean air and water policies and bills that provide protection for government scientists. The April 22nd march is a way for scientists to take a stand against the injustices inflicted by the current administration. It’s important that scientists make their voices heard, but we as scientists also need to make sure that the message we are sharing is a clear one: Scientists and researchers are here to help make our world a better place, and we stand beside everyone, in solidarity, for a better tomorrow.

A new study shows how a bee’s exposure to pesticides can cause significant changes in its scent memory abilities. The chemical formulations that kill mites may be non-lethal but can still harm bee populations.

Findings reported in the January issue of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry found that bees exposed to a pesticide used to exterminate mites within honey bee hives have changes in their behavior. They also found that these changes could be related to the expression levels of genes that encode key proteins in the brains of bees. In particular, three genes essential for scent memory were changed after pesticide exposure. Researchers from the University of Toulouse and the Jean-François Champollion University in France conducted exposure experiments with Western honey bees. Bees were exposed to the mite-killing pesticide Apilife Var for 11 months, and gene expression levels were compared to levels in the brains of unexposed bees. The study also evaluated if pesticides changed the way bees responded to scents. Apilife Var is a pesticide that kills mites and is made of natural extracts such as thyme, menthol and eucalyptus. These pesticides are effective against bee mites and are also known to affect cognition in mammals. Studies show that thyme extracts help rats complete maze tests and menthol can improve memory in rats. The protein expression levels of bees from this experiment showed seasonal differences during winter months. Three proteins decreased in bees who were exposed to pesticides 2-3 months after the start of the treatment. The proteins include transient receptor potential–like (TRPL), resistance to dieldrin (RDL), and Apis mellifera octopamine receptor 1 (AmOA1). In bees and other insects, TRPL helps bees avoid harmful chemicals. In theory, changes in the amount of this protein could cause confusion on whether a chemical is toxic or not. This could potentially cause bees to engage in unnatural behaviors, such as seeking out environments with harmful chemicals. The other two proteins studied are RDL, a neurotransmitter receptor and a neurotransmitter receptor that is crucial for learning. The study also found that chronic treatment with pesticides changed the way bees responded to scents. Exposed bees were more likely to respond to a scent that they were conditioned to associate with food. These bees were also more likely to remember that the scent was related to food after conditioning treatments. These findings provide additional understanding of how the pesticides can impact honey bees. Other studies have shown how these chemicals can hamper behaviors like learning, foraging, and scent memory. The genes studied in this paper are found in the octopamine pathway and includes proteins related to scent memory, sugar responses, and labor division. High octompamine levels are also correlated with bee anxiety. Long-term use of pesticides are associated with widespread honeybee population losses in Europe. A retrospective study showed that close to 10% of the honeybee population decline could be attributed to pesticide use. In 2002, new oilseed rape plants were introduced in the UK with seeds already coated in pesticides. Since the pesticide is water soluble, the plant takes up the chemical from its roots and the pesticide then circulates throughout the plants stems, leaves, and flowers. The coated seeds were a “key innovation” that avoids the need to regularly spray chemicals. However, the widespread use of the pesticide-covered rapeseed, and the exposure of bees to the pesticide while foraging, is now thought to be associated with bee population declines. Three pesticides from a class known as neonicotinoids were banned by the EU in 2013 because of their harmful impacts on bees. Farmers were concerned about the ban but there were no reported decreases in rapeseed oil yields in the UK after the ban. The use of these types of pesticides are still under review by the European Commission. |

Archives

August 2018

Categories

All

|

Addtext

RSS Feed

RSS Feed