World mental health day: Coping with stress, anxiety, and the rigors of a researcher’s life10/12/2016

Some Mondays end up being more Monday-ish than others. This week started with a particularly Monday-ish Monday, not in that any one thing was extremely challenging or upsetting but that it felt like things kept piling on. I woke up reading the commentary on the previous night’s dreadful excuse for a US Presidential debate, which itself came after a weekend of voiced concerns on Facebook and Twitter about brushing off comments made about women as “locker room talk” or “alpha-male banter.” Not to be one-upped by America, of course, the UK decided to fan the Brexit furor, this time discussing how to “name and shame” companies that hire non-British talent. In theory, companies would have to disclose how many expats (like me) they hired in the thought that sharing this information would be a disincentive. This would in theory include almost every university here in the UK, not to mention countless other research institutions here. The combination of this acrid news from both of the places I consider home, combined with work deadlines related to collating comments on a manuscript and dealing with freezer repair logistics, turned the start of this week into the epitome of a Monday.

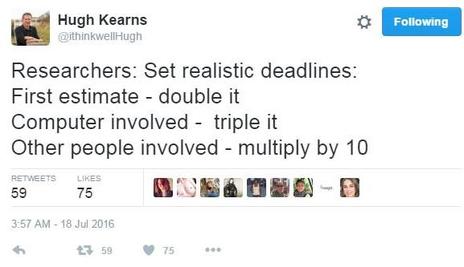

Stressful situations, even if they are just another Monday sort of Monday, can lead to self-doubt, anxiety, and imposter syndrome. They can bring out frustrations or worries that in a normal day might go unnoticed. It’s for this reason that World Mental Health Day is such a crucial day to remember, especially for those of us in the academic and research sectors. We are constantly being judged by our results, critiqued by our reviewers, and wondering if and when the next job, grant, or statistically significant result will finally arrive. These may all reflect the reality of just another day in the office of an academic researcher, but when this day is compounded by either external stresses from outside of work or internal pressures that you set on yourself, stress can become a real problem. I am fortunate enough to not have experienced many significant external stressors in my life. Apart from the occasionally Monday-ish Mondays, my life treats me very well. I have a wonderful husband who supports me every day, friends and family who look out for me on a regular basis, and I’m in good health with some savings in my pocket. I know this is not the case for many people and I won’t pretend that “I know your pain” or try to convince you that this blog post can make everything better. But what I do struggle with, and what I imagine other researchers might also empathize with, is a large amount of internal pressure that I put on myself, pressure that can occasionally build up to unhealthy levels. I’ve seen a lot of PhD students and aspiring academics/researchers who have similar personality traits. In general we tend to be organized, Type-A individuals, the ones who sit in the front of the classroom with a fleet of colored pens for taking notes and who already know the answers to every question. Because of the nature of our work, we also tend to be very independently driven. We’re the ones that don’t have to be told to do something in order to do it. It’s the reason we publish without submission deadlines and finish lab work without a boss telling us exactly what to do. This is a great trait to have as an academic, but feeling like you’ve always got to do something can leave you with a classic case of academic guilt: no deadlines or bosses, but always something you just have to do. As an undergraduate student, I was the one who made her own color-coded flashcards and began essays as soon as they were assigned. In graduate school I published two first-author papers, won numerous presentation awards, and was the ‘golden child’ of my lab, one who could never seem to do wrong. I was driven, always busy during the day while keeping up with emails and volunteer work in the evenings. I felt like I had a decent work-life balance, I didn’t go to lab every weekend and I took time off to visit family and to travel. But even with breaks, I’m a person that is almost always on. There’s always something to do, something to do better than before, something to think about, something to get ready for. This mindset has been useful in keeping me on top of my work and my career as a graduate student and now as a post-doc. It works when everything around me is going well, but when something cracks on the other side of my internal pressure gauge, I burst. When I was faced with uncertainty in extending my post-doc contract, I found myself torn down by panic attacks and overwhelming feelings of despair and self-doubt. When I was struggling with conflicts or loss among family and friends, I found myself unable to relax or enjoy life. When I was stressed about an upcoming deadline or meeting, I found myself stuck in an endless loop of working on a problem for so long that at some point I’d realize that I had just been staring off into space for several minutes not really working on anything. I’m sure I’m not the only person who has run into problems with anxiety and stress, especially when work and life gets confounded or when they become out of balance. It’s hard being self-motivated when our way of working through problems is to keep working -- even when it’s detrimental to our work, our lives, and our mental state. While there’s no simple solution to the problem of how we deal with stress and work-life balance, here are a few pointers which have helped me face the past few months with a bit more calm and resolve: Let yourself disconnect and refocus. It’s hard to disconnect when email comes to your phone and the problems of your day seem to sit in your mind all evening long. One way to help this is to find a place in your day or in your week when you allow (or force) yourself to disconnect. My favorite part of the week for refocusing is tae kwon do class. It’s an hour-long session twice a week where my phone is off and my mind is set at the task at hand, which is no longer emails or data analysis but stretching and sprinting. I get to take all of my frustrations and channel them into punches and kicks, and at the end of the class I feel refreshed and refocused (also sweaty and exhausted). Martial arts aren’t for everyone, but seek an activity that suits your style that lets your mind do the same, be it a yoga class or a glass of wine in your bathtub. Mourn or get mad, and then try to move on. Let yourself be sad or upset when things are tough instead of trying to convince yourself that everything is OK. Listen to your favorite angry song when you have a bad day or cry out your story over the phone with your best friend. It’s healthy to let yourself be upset by things that are upsetting. But a key point in picking yourself back up again is to try to move on from the situation. Listen to your angry song and then pick a motivating/upbeat song to help switch your mood to something more positive. Cry out your story to a friend and then watch a dumb video on Youtube that makes you laugh. These moments of transitioning between emotions can help give us perspective: yes, life is upsetting, but it also moves on, and so can we. Have a network of people looking after you. Regardless of what sector you work in, you’ll meet a lot of types of people. Unfortunately one of those types of people will be jerks. People who are only looking after their own interests alone or who are mean, rude, or otherwise unsavory to be around and to work with. I get really frustrated by jerks, to the point that it can bring out my anxiety and stress as much as a hard day at work can. Because of this, I take comfort in having non-jerks by my side with whom I can talk to when I feel like the jerks are taking over the world. Especially as a PhD student and early career researcher, having a network of positive people around you, people who support you and value your career/professional development, can make all the difference. Treat yo(ur)self! In a career that’s full of critiques and judgements about your work, learn how to be your own cheerleader. It’s good to stay motivated to keep working hard, but not at the expense of your own self-confidence. An easy way to do this is to learn how to celebrate the good, no matter how big or small it is. Did you finish editing a paragraph of a boring manuscript? Congrats! Make a second coffee and scroll on twitter for 10 minutes. Did you finally submit your dissertation? Congrats! Tell all your friends and coordinate a time for drinks. Part of finding a good balance with mental health is to learn how to reward yourself instead of always looking for things to be done, fixed, or improved upon. Don't weigh your self-worth on external metrics. It’s easy to spend time comparing ourselves to others or getting into the mindset that we just need another paper or award and we’ll finally feel good about are accomplishments. Rewards won’t always come and it’s easy to look at someone else’s life on a piece of paper or online and think that they’re much better than we are. Put value in yourself by things that don’t have an external measure to them. Don’t rely on citations, Twitter followers, or the job you have right now to be the only things that define you. Your skills, your passions, your experiences, and most importantly you as a person have self-worth on their own. I’m happy to have ended this week’s Monday on a good note, thanks to a good tae kwon do class followed by a session of night-writing. While I write this blog for graduate student and early career researchers primarily, in a way it’s also a place for me to speak to myself and to try to reconcile my own frustrations and stresses. But hopefully this blog isn’t just me talking to myself but can also help you find your own way forward through the rigors of an academic life!

It’s strange to think that it’s been seven years since that sticky, sweltering August day when I began my journey as a PhD student at the University of Florida. The sun was relentless for those first few weeks of the semester during the 15 minute walk from the former-pony barn-turned-laboratory to the shiny new health sciences buildings where my molecular biology class was held. My first few weeks of bumbling around in my new lab home, the Center for Environmental and Human Toxicology, felt as relentless as that boiling summer heat, and I had this undying sense that I had no idea what I was doing.

Between the molecular biology class that kicked my ass and the lab rotations, which I spent attempting to learn how to culture cells for the first time, I was relieved when the first semester of grad school was over—and thankful that I had survived it. The whole ordeal was an endless mix of gaining confidence when something went right and feeling incredibly ignorant when things went wrong (which, in my world of cell culture, was more often than not). I had spent my undergraduate career feeling pretty smart and sure of myself, and all of a sudden found myself 1300 miles from home and feeling like the dumbest person in the entire world. But this lack of confidence didn’t last forever. With the first semester under my belt, things soon started to click. I was learning how to think about experiments in a clearer, more scientific way, instead of just doing whatever came to mind. I had a great working relationship with my advisor and found a strong support group in my office mates. I even started to jog on a regular basis for the first time in my life—there was something about those pastel dusk colors on Lake Alice that seemed to call to me. I had had a bit of a rough start, but in the end I found my footing and was able to hit the ground running (both figuratively and literally). With the undergrads here at Liverpool well underway in their studies, our institute and other research groups here on campus are now in the process of formally welcoming new PGR students. After seeing all the new PhD and MSc students start to flood our labs and institute hallways, I found myself reflecting on the patchy start to my own PhD career and wondering if there could be a better way that I, or anyone coming into this new chapter of their lives, can start things off on the right foot. Starting anything new isn’t easy, be it a semester, a job, or even just a new hobby. The start of your graduate career might come with more changes than you initially expect. As a student you’re used to going to class, studying, and staying focused on your grades, assignments, and exams—but being a PGR is a whole different ball game. Even if you have done some lab work before, there’s a big difference between a summer research project and a PhD project that spans 3-5 years. The stakes are higher, the experiments are more complicated, and (especially if you’re in the UK), you’ve got a very limited time in which to make it all come together. Especially if you’ve come directly from a Bachelor’s or MSc program and only did a little bit of lab work, you’ll find the transition to a 40 hour-per-week research gig to be a challenging one. This is certainly not an exhaustive list, but here are a few suggestions on what you as a new graduate student can do during your first semester to get your post-graduate career started off in the best way possible: - Take time and make time to read. Reading papers isn’t just something you do to pass the time while not working in the lab or as a means of torture by your PI when you’d rather be getting new results. Reading as well as critically evaluating the literature in your field is absolutely crucial for both understanding what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. These papers are the foundations of your project and how results previously generated led to where your project stands now and where it will go in 3-5 years’ time. The way these experiments were done, the caveats of each conclusion, and the scientific logic that led from one paper to the next are key for you and your project. Your goal as a PGR is to now fill in a gap within the knowledge base of your field. You might spent your first month or two reading a lot of papers, but remember that reading the literature isn’t just something you do in the first semester and the last semester (while you’re frantically writing your thesis). While you’re in the early stages of your PhD, make it a habit to read papers on a regular basis. In your first semester, figure out a way to keep yourself motivated, whether it be by hosting a journal club, buying a fleet of colored pens, highlighters, and post-it tabs, or writing a summary abstract of each paper that you can keep on the side until you’re ready for putting it in your dissertation. Making this a habit now will keep you on top of things and will keep you from feeling like you’re drowning in information when you get close to the end of your project. - Get into a rhythm with your PI. Some PIs are active in the lab and will meet with you and other group members on a weekly basis, others will be tied up between coursework and conference travel and you might not see them for weeks at a time. Regardless of who your PI is, take the initiative in your first few weeks as his/her student to get into a habit of making contact with her/him on a regular basis. For PIs who are around regularly, this can be through a weekly lab meeting that keeps you on task. If your meetings tend to happen in groups but you like one-on-one feedback, feel free to ask for a separate time to talk to your PI about your project. If you have an on-the-go PI, get in the habit of sending an update email once every week, regardless of what country or conference room they’re in, to let them know what you did that week and what you plan on the next. By taking the initiative early on to establish regular communications between you and your PI, you can prevent belated surprises from popping up in your advisor-advisee relationship. In the early stage of your PhD, you should also talk with your PI about the expectations from the project. You’ll want to find out things like How much do they expect to hear updates from you? How many conferences do they want you to attend? How many papers do they expect? From your perspective, be sure to find out How will she/he stay in touch with you while travelling? How will he/she help you find a job when you’re finished? Will he/she be flexible if you have to travel home to see family or need to take a holiday? These conversations early on in a PhD program might seem unnecessary or too serious, but making sure expectations are clear and up front can prevent stress or strain in your relationship by ensuring that there are no surprises on either side. (A tweeted suggestion from the Liverpool PGR development committee) Review your skills and ambitions and use them to make a plan for your own professional development. It’s OK if you don’t know what you want to do after your PhD—most of us don’t, and those of us that think they know (like I did) might change their mind a year or two into the program. But you don’t need to know your precise career path to have a few big picture ambitions in mind. Think about what’s inspired you towards a career in science. Would you like to teach? Do applied research? Organize research groups and manage projects? Work with data? Work with animals? Work with patients? Thinking of your big picture goals early on can help you find new career options as you go along, jobs that you might not have initially envisioned but that actually fit in perfectly with your goals and ambitions. While reflecting on your big picture ambitions, use your first semester to think about what skillsets you currently have and where you could use some additional support. If you really want to teach but have only been involved with courses and teaching on a small scale, ask your PI to help you find some additional teaching experience. If you want to work with data but aren’t familiar with programming or computers, work with your PI to set aside time in your PhD program to get the in-depth training that you’ll need for the next stage of your career. Picturing your ambitions and visualizing what would be best for your professional development will help you get through your PhD and out to the other side with a good job in hand. Strike a balance between perfectionism and sloppiness. Especially if you’re coming from program where coursework and assessments were the focus, you might still be in a mindset of making things perfect. From pristine essays to using a ruler to underline words in your textbook (incredibly, I have met people who actually do this), many who are attracted to sciences are Type A personalities: we tend to thrive on organization and perfection. But as you’ll soon find out, you can waste a lot of your precious PhD time trying to make a figure look just right or obsessing over minimizing the variation for some experimental parameter to a level not needed for good results. But there is a need for balance: not being perfect is not an excuse to be lazy, and if you forget this fact you’ll soon find yourself on the receiving end of a discussion about the importance of graph quality when you show up to a lab meeting where your axes aren’t labeled. This first semester can be a time for you to learn how to strike the delicate balance between caring too much versus not putting enough effort into something. You might have to learn this the hard way the first time around (as I did when given a lecture about axis labels) but this is best to learn sooner rather than later during your PhD. Enjoy it! Your PhD is the time in your career when you get to focus on your science, your research, and your own professional development. Any job you do after this one, be it in an industry lab, an aspiring academic, or someplace not even on your radar screen yet, will have less of a focus on you than your PhD. You’ll be juggling multiple projects, working on getting results for your boss/company/organization, or applying for grants and describing your research and aspirations in a way that will appease funding agencies and collaborators. Your post-graduate career is also a time when one of your primary goals is to learn. Use that time to go to seminars outside of your department, attend conferences for the sole purpose of listening to presentations, and take a course on something just because you’re interested in it. Work hard, but make sure you take time to learn, explore, and enjoy the journey! One last point of advice: be sure to check out the resources available from your post-graduate department/graduate school at your University. This group will be able to help you get the best out of your experience as a graduate student. You can also check out our previous posts focused on professional development. Best of luck to all of those starting out this semester. Remember to work hard when you need to and enjoy a 3:30pm pint on a Friday when you need (and deserve) a break!

Last week we had a fantastic introduction into this week’s topic from our guest poster Namrata Sengupta. If you missed Risk Communication 101, be sure to check out her post which focuses on why we talk about risk in toxicology, the process of risk assessment, and why we need to have accurate communications when talking about these risks.

It may at first seem that the theme for these last two weeks is only relevant for those doing toxicology research. While it is crucial in our field of research, risk and the importance of clearly communicating risk goes beyond toxicology. From issues in public health such secondhand smoke or issues on a much bigger level like global warming, talking about risk is prevalent in many areas of science. More broadly, risk appears whenever there is uncertainty in a decision that has consequences. For instance, in any research endeavor there is always some uncertainty in our predictions of the truth of the universe (i.e. the p-value). Knowing how to talk about uncertainties, risks, and the consequences of inactivity or a lack of understanding are crucial for any field. A few weeks ago I attended the “7 Best Practices for Risk Communication” webinar organized by NOAA’s Office of Coastal Management. The webinar was targeted to people who work with natural disasters or landscape restoration. Even though my work doesn’t venture much into the risk communication area, I thought the webinar was a good introduction and was relevant for anyone whose work enters into the territory of ‘risk’ related to human health or the environment. Even if your work or your outreach doesn’t have a focus on behavioral changes, these principles are a great way to help you get started with your own research-oriented communication activities. Before I go into a quick summary of the 7 best practices, it’s important to realize that the definition of risk communication is slightly different than what we discussed last week. In this webinar, risk communication was defined as “Exchanging thoughts, perceptions, and concerns about hazards to identify and motivate appropriate action” while last week we spoke more generally about “The interaction between environmental risk assessment scientists, managers, policy makers, and public stakeholders.” This first definition is less specific in that it doesn’t mention who is engaging in the communication, and instead defines this activity as a two-way conversation about a topic in which one of the parties is trying to motivate a change in the other. Webinar take-home message: Behavior change is a slow process. We won’t go into detail about every single part of the webinar, but for each section we’ll try to focus in on some of the most important points highlighted as the “Webinar take-home messages.” If your goal is to have someone’s lifestyle or opinion change, be aware that this will take some time. Your audience will come with a diverse set of preparedness or awareness, with some not thinking the issue impacts them at all and others already 99% on board with what you’re saying. Whoever your audience is, it will also be unlikely that their opinion will change after one meeting or one interaction. Another reality is that you might not be able to change their opinions at all, so be ready to deal with pushback from people who just won’t budge at all. Step 1) Have a plan: Know what you want and how you’ll achieve it. Webinar take-home message: Think of who else is talking to your audience. If you’re already an active science communicator then many of the considerations mentioned in this step are considerations you’ll already be aware of. Be sure to have a goal for what you want to say/achieve, know your audience, develop your message, be consistent, etc. In particular, the webinar made the point that we are not the only ones talking to our audience. Think about your own day: there’s long emails, #hashtags, and news that is updated on an hourly and faster basis as new information comes in. These information streams are flooding with opinions from experts, friends, and everyone in between on what’s healthy, what’s hazardous, and what’s should be the concern in your day-to-day life. Being aware of where else our audience will get information from can help you develop a consistent message in connection with what might be coming from other sources. For example: if your audience likes to hear news directly from friends on Twitter or Facebook, think about what those posts might look like and if you can to adopt a similarly friendly or narrative approach to make that initial connection. Step 2) Speak to their interests, not yours: Connect with your audience’s values on an emotional level. Webinar take-home message: Make the story about the audience and listen to them The presenters talked about a case study on Wetlands protection, where conservationists saw an apparent shift in their outreach efforts when they changed the discussion from “Save our wetlands because they’re nice” to “Save our wetlands so your homes won’t flood.” It might seem unscientific to think about communicating science by playing on the emotions of your audience, but communication without any empathy is always destined to fail. You can develop trust with someone by showing that you’re interested in their problems, not just your own. Another message I like from this step is to be a good listener: you can quickly learn what is important to someone by hearing things from their perspective. 3) Explain the risk (or the research): Help your audience gain an understanding. Webinar take-home message: Go from the top down As scientists we thrive on the details of the data before coming to a decision, but as people we thrive by seeing the big picture and how things fit together. When talking about a particular risk or your own research, start off with the impacts and then work your way to the nitty gritty. It can also help you make a connection by talking about science in a way that’s more obvious than error bars and biological replicates: residential flooding, asthma rates, and salmonella infections are all things that people can see and connect to. 4) Offer options (or actions) for reducing risk: Provide some hope instead of just doom and gloom. Webinar take-home message: Talk about both the small and big picture solutions If your message involves telling your audience how the world is going to end and there’s nothing they can do about it, you’ll lose them. People can only intake a certain level of feeling helpless and fearful about a situation and at some point will just stop caring about a situation entirely. Some topics are difficult to talk about in a positive light (“There’s ONLY a 20% chance you’ll get cancer!”) but giving a suggestion for how people can help mitigate some aspect of risks provides a positive spin to the situation, as much as it’s possible. A few examples include encouraging volunteer activities such as planting trees or providing better ways for people to properly disposing of unused prescription drugs. Having an empowerment to-do list will also help others feel more involved with the problem and that they can actually work towards a solution on their own. 5) Work with trusted sources: Teamwork to achieve a common goal. Webinar take-home message: Working with partners can broaden the audience for both of you. The workshop instructors presented a case study of a collaborative project between the NAACP, the Sierra Club, and a local bike shop who all worked together to put on a local bike tour. The event introduced community members to groups they didn’t yet interact with through an activity organized by groups they already had established trust with. Doing these types of cross-sector collaborations broadens your perspectives by allowing you to hear about other groups and how they communicate with their audience—perspectives you can use on how you communicate with your target group. This type of work can also lead to some new conversations among people you never thought you’d interact with—think of inviting a pensioners-only book club to your lab to talk about your research. You can then see the differences between their questions from questions coming from a group of primary school students or from your peers. 6) Test your message: Tell your story to someone who’s not in your research group. Webinar take-home message: ….and be ready to make changes when you tell it to someone else the first time. Nothing is perfect in a first draft, so if you’re preparing new material then allow for some additional time to react appropriately when you get feedback. It’s hard when you put so much energy into explaining something or making figures and designing graphics, but if it’s not working on a subset of your audience, it won’t work with the majority of them. Remember that your goal is to have a message click, not just to get it done the first time and move on with your life—so be ready to invest the time and energy to make it matter. 7) Use multiple communication venues: Understand where your audience is listening. Webinar take-home message: Meet your audience where they are Twitter and Facebook are great ways to connect—if your audience is on the website regularly and follows your posts. If you’re looking to reach an older or less tech-savvy target group (which is not necessarily the same in this day and age!), they might not find your message using a hashtag. Conversely, if your target group has a monthly meeting on Wednesday at 8pm at a local bar, show up and have a pint. Having a great message doesn’t do you any good if the message only gets to your social network. Know where your target audience is and where they go looking for information, and be there waiting for them. And with that two-week crash course, you are now ready for Risk Communication 301: Applied Risk Communication tactics. Get out into the world, craft your message, and get it to your audience in the place they’re looking for information. And if you’re wondering what the risks are in sharing your research with a new audience, you’ll be happy to know that engaging in risk communication has no potential hazards associated with its use or implementation. But it might be a good idea to bring your flood pants, just in case.

This week we have another collaborative post from guest blogger Namrata Sengupta. She’ll be introducing the concept of risk communication in environmental science and toxicology. Next week we’ll be following up on her introduction with a more detailed look at ways of approaching risk communication approaches and a review of a recent webinar hosted by NOAA. Enjoy!

“It is ironic to think that man might determine his own future by something so seemingly trivial as the choice of an insect spray.” – Rachel Carson, Silent Spring Background In 1962, the American conservation biologist Rachel Carson published a book called ‘Silent Spring’. She described the effects of man-made contaminants and their potential of harming wildlife. The book detailed a study on thirty five bird species which were nearing extinction caused by these contaminants entering water bodies, and the story facilitated the ban on DDT in 1972. The book is considered as the scientific foundation for modern environmentalism in America, including the establishment of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) in 1970 as well as the Clean Air Act (CAA) and Clean Water Act (CWA) later that same decade. Carson was an early pioneer of the field of risk communication. Her book powerfully displayed the combined intellect and thoughtfulness of a person who was a scientist, poet, nature-lover and activist all in one. She inspired a generation of people to become well-informed and to realize the importance of getting involved in environmental health research. In the modern age of chemical industrialization, the existence of the CWA and CAA has played a major role in protecting both wildlife and human health. Even 50 years since the publication of Carson’s novel, environmental science and toxicology continues to grow. From decoding manmade chemicals, understanding the complexities of cancer, or using advanced statistical techniques to explaining ecosystem dynamics, our field has expanded not just to labs and journals but also to applications and implications in public health policy and decision-making. Environmental scientists and toxicologists now realize the relevance of their work in policy making but are also constantly critiqued by industry, government, and policy makers who are using their work. Risk Assessment The US EPA developed guidance and structure for characterizing the hazards associated with exposure to environmental contaminants to both wildlife and a human population, which is called risk assessment. The purpose of a risk assessment is to evaluate the potential for exposure to a chemical in the environment as well as the potential impact of these chemicals. The process of characterizing the potential for chemicals to harm humans or wildlife through risk assessment is an important component of policy making. It provides scientific support for decision making and limits the pervasive social and governmental influences. But regulatory science is not always clear, neither to the government nor to the public. Because of this lack of clarity, the EPA is working to develop better strategies not only for risk assessments but also for communicating the implications of risk to the general public. What is Risk Communication? Risk communication is the interaction between environmental risk assessment scientists, managers, policy makers, and public stakeholders. For effective risk communication to occur, all impacted stakeholders for a particular setting should be a part of the communication process from the beginning. It is extremely important to identify relevant stakeholders (generally done as a part of risk management strategy) and to develop communication streams to fit their needs. It is also crucial to engage in two-way communication, where stakeholders are able to voice their perspectives, questions, and opinions directly to scientists. One of the biggest challenges of risk communication is that it is generally the most overlooked aspect of risk assessment and management. Scientists often forget the importance of being able to communicate effectively about their research and scientific opinions when working with a diverse audience. This lack of effective communication has occasionally challenged the ability of industry and government officials to interpret the scientific evidence which can inform regulatory affairs. Another challenge is how much information should be shared directly with the general audience. In today’s world of the Internet and mass media playing critical roles in science communication, scientists need to be cautious about the interpretation of their data. Strategic training, information sharing sessions, and orientation with the public should be planned by both scientists and policy makers when discussing topics which affect wildlife and human populations. Why is Risk Communication important? Our environment, food, and personal health are threatened by exposure to environmental pollutants and bacterial hazards on a daily basis. While there are research and quality control safeguards towards protecting us and our ecosystems, there are times when we may encounter an additional crisis event, such as an oil spill. The communication associated with both daily and event-based risks needs to be a continual and evolving process and not just for a one-time crisis management initiative. The topics widely covered under the umbrella of risk communication are generally: 1. The levels of risk (environmental/health) 2. The significance of the particular risk 3. The regulations, decisions, and policies in place to deal with these risks Previously, risk communication was often thought of as a “linear process”, but now experts and all concerned stakeholders understand that it is a “cyclic process”.

In next week’s post, we’ll go into more detail on methods for how to use the cyclic process of risk communication. A big thanks to Namrata for introducing us to risk assessment and communication! For more of her writings, be sure to check out her science and outreach blog.

Since the next semester is fast-approaching, the editors of Science with Style and the University of Landau’s EcotoxBlog are collaborating on a guide to help students find their own style of studying. Enjoy!

As Ned Stark (or maybe it was actually your professor) once wisely said: Autumn is coming. Do you find yourself still in relaxation mode after a leisurely summer, or can you already sense that calm before the storm? We’re already well into September, with the next semester looming ahead of us in UK, Germany, and many other parts of the world. Regardless of what mindset you’re in, you’ll soon find that the rigors of the upcoming busy semester of exams and assignments are soon to come. Everyone has a different way of engaging in coursework: some of us take a lot of notes, others listen, and others, well, don’t really do the whole going-to-class thing. But at some point at the end of the course, we all have to take an exam, write a term paper, or in some other way show the professor that we learned something. Your professors will spend a lot of time teaching new concepts, explaining complicated subjects, and trying to inspire some interest in a favorite topic of theirs. But one thing a professor can’t do is to teach you how to study in a way that you can retain and reuse knowledge while being examined. Therefore, we here at the Ecotox Blog and Science with Style have collated a few tips that will make the use of your valuable time more effective: The basics First: Check out this video from Vox, who provide the following tips on their YouTube channel: Don’t just re-read your notes and class readings. Re-reading isn’t helpful for retaining information. Another downside to re-reading is that the process can make you feel like you’re learning when you are really not. Reading in itself is a passive activity, but when you’re taking an exam and need to recall information, you’ll be doing something much more active. You’ll need to practice active learning if you want to be able to remember a concept thoroughly while being tested on it. Quiz yourself. Flash cards are an easy way to do this, and depending on your own style there are lots of ways to go about making and using flashcards. You can make card-stock notecards on your own, but if you prefer a more tech-savvy approach you can make your own cards to read from your computer or smartphone. Flash cards provide that active component of studying that your brain needs in order to be able to recall information and facts on demand—just like you’ll have to do during an exam. An important suggestion in the video is to put cards that you get wrong back in the deck, which forces you to review the concept again and again until you get it right. Visualize concepts. Create a new analogy for a complex reaction or process. Creating this analogy forces your brain to actively process the information, as you need to really understand the concept before you can explain it in a new way. You can also come up with personal connections to help you remember how things connect, such as aligning concepts to characters or a plot from your favorite TV show, game, or movie. Avoid cramming! Cramming usually doesn’t work well, and even if you pass the exam the information will only stay in your brain for a short while. Especially if the course covers concepts that you’ll use throughout your time in university, it’s worthwhile to invest that extra study time. With better study approaches, you’ll be able to better remember a concept for a longer duration of time, not just to regurgitate it during one afternoon. Some more tips that helped us and our colleagues during our own student times Explain an idea back in your own words. Test to make sure you’ve got a concept down by trying to explain or teach it to someone else. You can work with classmates by organizing “explaining sessions” with each other to see if your explanations are on par with how the system actually works. This practice will also help you prepare for exams where you’ll have essay portions, as it forces you to practice how to explain something before you’re given the task on paper. If you’re not good at staying on-task or studying independently, find an accountability buddy. Some of us find it easy to stay on task with independent assignments like studying or writing, and others might feel the need for an external or firmer deadline. The problem with exams is that there’s no deadline until you get to the exam-which is not when you want to start studying. If you find yourself struggling with procrastination, find a study partner in your class and schedule regular sessions to study together and hold each other accountable for keeping up with your study materials. Use a study group if you need one, but be sure to stay on target. If working with groups helps you study and keep on track, then forming a study group can be a good solution. But be sure that for each group meeting you have a plan of what you want to achieve and a deadline for how long you’ll work on something. Unstructured group work can quickly fall off track or get sidelined, but having a game plan before you start and a clear objective of what the group wants to achieve will make your get-togethers more productive. Have dedicated breaks. It’s exhausting to think of having to study “all day” and can also lead to unproductive minutes and hours if you drag things out for too long. Have a set start and stop time for when you’ll focus on studying or writing a paper. It can also help to have a dedicated study space, whether it be a corner desk in your apartment or your favorite spot in the library. Then when you’re done or need a break, you can physically leave the space and let your mind relax. If you’re worried of taking too long of a break, set a timer and allow yourself to do whatever you’d like in that set amount of time before getting back to work. Find your incentive. Speaking of breaks, we all know that learning or writing the whole day can be very frustrating and that doing something which makes you happy during a break can help you get through a hard day’s work. Just be sure to make your breaks more rewarding by ensuring that they stay limited in size and don’t become as long as a study session. Play one campaign of your favorite online game, watch one episode of your favorite TV show, or do a particular hobby you have for a preset period of time. We promise that this will cheer you up and that you will survive until the next break! If you’re frustrated or feel like you’re not getting something, ask for help. Even if you study independently, you don’t have to go through the learning process alone. If something isn’t sticking or you’re not sure you’re understanding a concept correctly, talk to your professor or a class tutor and get yourself on track sooner rather than later. If you miss out on understanding the basics at the beginning of the semester, you’ll be much more likely to miss out on understanding the important concepts that will build off of the basics. Don’t feel like you’re a failure if you don’t figure things out the first or second time around—TAs and professors are there to help you (they are even paid to help you do this!). So what now? Truth be told, studying for an exam or writing an exam paper will never be anyone’s favorite activities. But if you invest your time wisely and give some of these tips a try, you can work on finding your own style of studying and become a much more effective student. Being more effective will mean more successes for the amount of time you invest, and this will allow you to achieve what any student aims for: getting good grades while still having enough time for the nice things in life :) We hope guide had some helpful hints for you to study with style. Wishing you a successful start into the new semester! - Erica & Jochen PS: We are interested in what works best for you! Any other tips on mastering exams or term papers? Let us know by contacting us at Science with Style or the EcotoxBlog and we’ll spread the word. Any advice from those who already successfully completed their studies is also highly appreciated. PPS: Want to read more about their Master’s program in Ecotoxicology and their research? Be sure to check out Landau’s EcotoxBlog.

My husband and I spent last bank holiday weekend exploring the gorgeous scenery in and around Bergen, Norway. The weather on that late August weekend was what can only be described as distinctively Scandinavian. It’s a mix of gorgeous, sunny moments that reveal postcard-worthy scenes of rolling hills and fjords along with the constant threat of clouds and rain. The pictures taken during our hikes fail to capture the time we spent walking in the pouring rain and the ones from our incredible ferry ride through the fjords north of the city don’t show my husband and I in nearly full winter regalia, with hoods and hats to protect our heads from the intense winds.

Norwegians have a saying (which rhymes in Norwegian) about the weather: “Det fins ikke dårlig vær, bare dårlige klær,” which translates to “There is no bad weather, only bad clothing.” It’s a phrase that captures two aspects of the Norwegian culture: their love of being appropriately outfitted and their disdain for making an excuse not to do something. On the first day of our trip we did a long 22 km hike from Ulriken to Fløyen, and during our rainy ascent we were passed by numerous groups of fast-paced Norwegians. Whether they were big families or solo hikers, all of them seemed completely unphased by the wet and slippery rocks or their (likely) wet and uncomfortable socks. Coming back to the UK after the long weekend, it only took one rainy day to see the contrast between Scandinavia and the UK. An afternoon shower found numerous people caught in the rain without umbrella or jackets, wearing canvas-side shoes on a day forecast to be wet, followed by a general clearing out of the city center as soon as the wet weather came. Seeing this contrast between how two rainy countries deal with wet weather also brought forth another realization: when looking for a career as a scientific researcher, the forecast seems to always call for rain. The market is competitive, research budgets are tight, and a long-term contract might not always be easily in easy reach. Given that the forecast might not change in the near future, the question then becomes: what can you do to weather-proof your career? If you’re in the midst of a PhD, your main focus will generally be your own project. You’re thinking about lab work, papers, committee meetings, and all the other things you need to do just to get done. It’s exhausting to think about both finishing and what you’ll do after you finish. Post-docs and early career researchers might have a focus which is more ‘career’-oriented, but in the midst of the pressures of our own projects, grant proposals, and trying to figure out what comes next, the thought of actually getting there feels scary. But just as you wouldn’t go on a trip or on an errand run without checking the weather and bringing your sunglasses or umbrella or jacket as needed, you shouldn’t charge on ahead through a job without being ready for what happens when you step outside into the real world. The good news is that hauling some extra gear in your bag isn’t as exhausting as you think it is, since a lot of these ‘weatherproof’ skills are becoming more easy to find and more packable than ever before. Regardless of what stage of your career you’re in, here are a few things that will make your career ready for whatever weather lies ahead: Take a skills inventory. Before you run off to the outfitter store to buy one of everything, start off by figuring out what you already have. Review your current CV and give it a critical read-over, as if you were reviewing the CV of someone applying for a job in your lab. Think about the skills that you have or what you do every day, be it emails or coordinating lab meetings or multi-tasking in the lab and office. Is your CV up-to-date and does it capture all your skills? Are there courses or training programs that you completed outside of your standard curriculum that might be useful later on? Is there an activity you did as volunteer work or as the leader of a group that’s relevant and can be highlighted? Doing a skills inventory involves thinking critically about all the work you’ve done, both in and outside of the lab, and how your skillset can be presented in a way that shows its relevance to a potential employer. Especially if you haven’t thought about your CV for a while (or since you first made it), going through your extracurricular activities and professional skillsets might help you realize there are skills you didn’t know you had-just like how digging through your closet at the start of a new season reminds you or a few pieces of clothing you forgot about since you didn’t wear them for a whole year. Check the forecast. A forecast is rarely perfect, but it can help you figure out existing weather patterns and to get a sense of what might lay ahead. In your career, you won’t be able to get a 100% accurate prediction of what the field will look like once you’re actually ready for a job, and you might not even know exactly where you want to go next. But at any stage, you will have some amount of an idea of what or where you want to be, whether it’s a city, region, sector, or field. Regardless of where you want to go, check the forecast by scoping out the job market well in advance. Find a few job websites or email listservs to be a part of and take a look at what the jobs are looking for. Since you’ve already done your inventory and you know what gear you have, you can figure out if you have all the gear you need. If you’re missing something, you can decide what you need to pick up before you hit the road. Read some travel reviews to find out what it’s really like. You probably already have an impression of what your ideal career and your dream job will look like. You know that all you need to do is get the post and you’ll love it! It’s similar to getting a postcard in the mail of some picture-perfect exotic scenery that makes you instantly say I wish I was there…But before you fall in love with something you’ve never seen first-hand, read the reviews. It’s here that your professional network can help set you up for success. Connect with your colleagues and mentors and reach out to new contacts who work directly in the field you’re interested in joining. Arrange an informational interview over skype, ask to see their CV and/or have them look at yours, and see if their experience matches up with your preconceived impression. A 5-star review can be just the thing you need to give you the inspiration and confidence you need to set forth, and a less-than-stellar review can show you that there might be a better destination on your horizon. Have one of everything in your bag. It’s tempting to only bring flip-flops and shorts on your tropical vacation, but the Caribbean islands can still get hurricanes. Just as it’s good to have an extra rain jacket, it’s also a good idea to keep your own portfolio of skills diverse. Your time as a PhD student and ECR is perfect for this, as it’s the stage in your career when your time can be a bit more flexible. You can use a wide assortment of techniques and should feel encouraged to try new things on a frequent basis instead of doing the same thing every time you’re in the lab. If your work is computer-focused, be sure to get try programs or languages that others may use. That way if you end up with an employer that prefers one of the other, you’ll be able to say that you at least have some familiarity with the one they’ll use. Once you arrive at your destination and know you’ll stay there for a while, you can stock up on things you’ll need more of. But until you get there and know for sure what you’ll need in your bag, play it safe and keep a little bit of everything on hand. Adopt a Norwegian attitude to bad weather. The job market is a rainy place to visit, and it’s tempting to want to stay inside the warmth of your current job or project when you can hear the sounds of the downpour outside. But that doesn’t give you an excuse for staying inside: at some point you have to suit up with the best outfit and equipment you have and give the day all you’ve got, even though you might get your boots wet or your hat blown off. The best way to get through the downpour is to approach it as optimistically Scandinavian as possible and remind yourself “There is no bad job market, only bad cover letters.” There won’t ever be a “Five easy steps to your dream career” post here on Science with Style, since finding a job is as much of its own journey (with the occasional bit of rain and thunder). Preparing yourself now by making a thorough inventory, picking up some tips from colleagues, and adding some new skills to your pack, you can gain the confidence and the preparedness to be able to go for it, regardless of what’s waiting for you. Walking through a rain storms is certainly not an enjoyable feeling, but occasionally a rainy day will bring a nice reward when the clouds clear. All it takes to find your job at the end of the rainbow is to take the first step outside and get out there!

I’m taking a break from the blog both this and next week to focus on some other writing projects, but in the meantime I thought I’d delve into the archives of my personal blog I kept while a graduate student. This one was one of my early attempts at science communication and focused on a restored lake which was in the middle of the University of Florida campus. Nice to have a bit of a walk down memory lane to remember the good times in The Gator Nation. Enjoy!

“The Story of Lake Alice: Finding the right balance between nature, administration, and aesthetics” Originally published on "A toxicologist's tale", 11 Sept 2012 5pm rolls around and you’re more than ready for the end of the day. Whether your day is spent in class, at work, teaching, or doing research, we all need a place to unwind after a busy day here at UF. Many of us seek out natural areas to cleanse our minds and bring perspective to the tumultuous moments we go through each week. For many students and staff, the hallmark oasis of these natural areas on campus is Lake Alice. It’s a place for relaxing walk with friends to look for alligators and soft shell turtles, for a vigorous jog through the winding trees near the Baughman center, or for waiting patiently at the bat house for dusk to fall. Lake Alice provides us with so many easily accessible and engaging ways to enjoy the many pleasantries of nature. But perhaps on occasion you’ve noticed things that made you wonder just how pleasant these natural areas on campus really are. Maybe a powerful smell as you jog along the north shore, the extremely turbid waters in the creek at Gale Lemerand and Museum Road as you walk downhill to the commuter lot, or the incidences when the whole lake turns bright green. You’ve likely asked yourself what these events mean for our lake, if our lake is as clean and healthy as it should be, and if you should be concerned about any of it. But before jumping into conclusions about how healthy our lake really is, we need to take a step back and understand how the quality of water bodies is defined and the numerous roles our treasured Lake Alice holds for our campus. Lake Alice has a rich and varied history since the lake and the land around it was purchased by UF in 1925. At that time, the only sources of water input into Lake Alice were rain, storm water runoff, and untreated sewage. As UF continued to expand, the direct input of sewage into the lake was no longer seen as a sustainable option, so treated effluent was discharged starting in the 1960’s. In 1994 the Water Reclamation Plant was built, and now the treated effluent is no longer discharged directly to the lake but is piped to one of Lake Alice’s discharge wells. Lake Alice currently receives water from stormwater and irrigation runoff that enters from the connecting creeks. Lake Alice is not here only to serve as a oasis for us: Lake Alice and the other lakes on campus are also the official storm water retention ponds for UF. These on-campus lakes are under the regulation of the federal government as part of a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit that the university holds. Holders of these permits are required to identify and prevent non-point sources of pollution, which includes things like irrigation chemicals and contaminated runoff from roads near the lake and connecting creeks. As part of the broader plan for waters on campus, UF also wants to help Lake Alice reach Class 3 water quality standards for the state of Florida. Meeting these criteria would mean that the lake is suitable for “fish consumption, recreation, propagation and maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife.” Lake Alice is also a recognized conservation area (so no fishing or swimming allowed, even if the lake does meet Class 3 standards) and it serves as home to over 75 plant species and 60 animal species—including our university’s mascot the American Alligator. With all of these different functions and regulations—storm water retention area to the federal government, a potential Class 3 water body for Florida, and a wildlife conservation area—how is UF keeping up with the array of unique demands from administration and nature alike? One approach to monitoring if these demands are met was by the establishment of the Clean Water campaign in 2003. Dr. Mark Clark, one of the founding members of the campaign and a professor of the Department of Soil and Water Science here at UF, is currently overseeing the outreach and public awareness efforts of this group. These activities include installing drain markers to inform people that campus drains flow into Lake Alice, volunteer clean-up efforts, and educating the public on water quality issues. Another major facet of the Clean Water campaign is monthly water quality sampling events that have taken place since 2003 at 20 locations all over campus. Some of the locations include the creek near the New Engineering Building, Hume Creek in Graham woods, and the Baughman Center bridge. Based on the water quality data collected so far, there are two main chemicals that have the potential to cause problems for the competing regulations imposed by administration and the natural requirements for having a healthy lake: nitrogen and phosphorus. Both of these chemicals can cause algal blooms and plant overgrowth as well as decreased oxygen levels. Decreased oxygen can cause fish deaths and lead to an imbalance in the different types of wildlife that live at the lake. In addition to the work by the Clean Water campaign, students of Drs. Dan Canfield and Chuck Cichra have been collecting water quality and fish population data as part of the Introduction to Fisheries Science (FAS 4305C) and Fish and Limnology (FAS 6932) courses for over 30 years. In lectures and hands-on field work, students learn how to collect and interpret water quality readings and how to estimate fish population structure and size. One of the lessons these students learned when the course was first offered is that an aesthetically-pleasing lake is not always the best lake for fish. In previous years when the lake was bright green—before the treated effluent was re-routed—Dr. Canfield and Dr. Cichra’s students were amazed at the large size of bass and other sports fish they caught. “They had been taught for years that a green lake was a dead lake. It didn’t take them long to realize that wasn’t the case for many of these fish species,” said Dr. Canfield. Over the years as the lake has become clearer, data collected by Dr. Canfield’s class indicate that fish populations have declined both in size and number, and there are also fewer ospreys than in years past. Some fish kills have occurred, but Dr. Canfield indicated that these were caused by severe low temperatures and invasive species such as tilapia. Dr. Canfield also stated that “Water quality has become very focused on issues of phosphorus and nitrogen, while ignoring other important issues like bacteria.” Fish living immediately at the discharge site previously had a high rate of infections and fish in the lake still experience these problems, which demonstrate the need for a water quality plan that also looks beyond chemical measurements alone. So what is the future of Lake Alice and other natural areas on campus? “The next phase is for the university to decide what steps to take to balance the dual roles of having an aesthetically-pleasing lake and an area appropriate for conservation goals,” said Clark. This means incorporating what we know about the watershed from the water quality data that the Clean Water campaign collected into the future goals of our university and identifying the roles it wants Lake Alice to continue to serve. What does this mean for the rest of us that don’t have a direct impact on the decisions made by the university? While we may not be able to reduce irrigation run-off or help larger fish come back to the lake, there is a lot that we as members of the Gator Nation can do to take ownership of the health and well-being of the waters on our campus. For more information on the Clean Water campaign, visit http://campuswaterquality.ifas.ufl.edu to learn about events and activities. You can also become a part of UF’s wetlands club and participate in volunteer clean-up efforts around campus and in the Gainesville area. To learn first-hand about lakes, fisheries, and water quality issues, sign up for Dr. Canfield’s and Dr. Cichra’s course, taught each Spring and open to any junior or senior-level students with an interest in the subject. Our lake has undergone numerous transformations during the changes in water inputs and usage over the years, and the lake will likely not remain in its current state forever. The future of the water bodies on campus hinges on finding the correct balance between nature, administration, and the future expansion of our university. And while you may not be able to have a direct impact on decisions made by our university, you can do your part to help protect these important natural areas by becoming aware of the issues and history of our lake and becoming active in clean-up or educational efforts.

Every Monday and Thursday night, I take a 15 minute train ride on the Northern Line from Liverpool Central for my biweekly tae kwon do lessons. The classes vary throughout the week: sometimes we focus on technique, sometimes we focus on strength and endurance exercises, and some weeks we do so much kicking and sparring that I can barely manage the walk back to the train station. Last week we had our last two lessons before a summer break, starting with a seemingly relaxed warm-up that led into an intense 30 minute sparring session.

During our sparring prelude, someone asked about a former class attendee who hadn’t been around for a while. Our black belt instructor Paul said that he didn’t think the student in question would ever return, and wasn’t too surprised about it, commenting that the current number of students who had taken his class versus those who had completed their black belt was similar to what he had seen at other schools, including when he earned his black belt. The black belt ‘graduation’ rate according to Paul is around 1 in 35, so of 35 students that start tae kwon do training, only one will actually earn a black belt. Call it tae kwon do attrition or just the fact that not everyone’s cut out for the sport, but it’s no surprise that not everyone makes it to black belt stage. It’s a tough sport, as my legs can attest to after our final lesson of the summer last Thursday. But Paul’s comment also brought to mind thoughts of the parallels between training in martial arts and going for a PhD and career in research. The completion rates are a quite a bit higher for those going for a PhD (50-60% in the US and closer to 70% if you’re here in the UK), but the processes have a lot of overlap. It’s not that people going for a PhD or black belt who don’t finish are lacking in intelligence or athleticism, it’s that both processes require more than you expect at first glance. To succeed at both, you can’t just be intelligent or be physically fit: it takes additional dimensions of mental strength in order to succeed. After writing two previous posts that focused on the connections between scientific research and tae kwon do, namely in learning how to fail and the balance between rubber and steel, I was inspired to revisit the topic and delve more deeply into the parallels between these two seemingly different activities and to focus on the aspects of both that might not be as readily apparent as the kicks and punches of tae kwon do and the papers and grants of a life as a career researcher. Both require you to humble yourself. Regardless of how flexible, strong, or fast you are, everyone in tae kwon do starts with a white belt. The color white symbolizes a person having purity due to their lack of knowledge of the martial art, and as you progress through the colored belts towards black you gain knowledge of new techniques as well as some much-needed control of your abilities. As you go from white belt to yellow belt to green belt, you’ll feel pretty confident. You’ll feel like you can take on anyone. But as you progress further and further, inching your way towards black belt status, you soon come to recognize how little you actually know and how much of an expert you are not. There is always a move whose execution can be further perfected, a stance that can be stronger or more elegant, and regardless of what level you’re at there will be someone in your class who’s above you in some way. Training to become a scientist is very much the same: we start off in undergrad learning so much all at once, progressing in our classes and lessons, maybe even getting a bit of lab work under our belt. But at some point we dive into the big pond of scientific research, where we find that the world is so much bigger and that what we know is so much smaller than what we thought. We gain knowledge through school and in our research, but part of learning how to be a scientist comes from recognizing how little we know and what we can do to get to the next step. …but both also require you to have a thick skin. Feeling like you don’t know very much is a humbling experience, but it’s also one that you have to know how to counter with confidence. In both martial arts and research, you have to balance the humbleness of recognizing your place in the world with the confidence of knowing where you stand. It’s easy to let feeling like you don’t know anything or aren’t good at something turn into you thinking that your lack of knowledge or skills will set you back permanently. Those who find success in both research and marital arts are able to walk this careful balance between humility and confidence, able to recognize where they can improve but to stand firm in the place that they are strong. Both require good senseis. A mentor or coach is crucial for success in both martial arts and in doing a PhD because both of these processes are not easy. It’s not as simple as just progressing from white belt to black belt or from undergrad to professor: you need time and a structured environment for reflection, assessment, and a critical eye to see the flaws and strengths that you can’t. And even though both endeavors are seemingly independent activities in that it’s your belt and your research, you still need a good mentor to show you the way and to encourage you to work and learn from others in the process. Both will help you find confidence but won’t automatically give it to you. I’ve heard a lot of parents say that they want their kids to get into martial arts because it’s an activity that builds confidence. But as someone who started white belt training as a 14 year-old shy kid who grew up to be red tag and slightly more outgoing and gregarious 28 year-old, it’s not just the sport that makes you who you are. Confidence is one of those personality traits that function best when they come from within. I greatly enjoyed tae kwon do as a kid, but found that I find the sport more enjoyable and more relaxing now that I’m more confident in myself than I was back in high school. Both martial arts and science are great at building up the confidence in those that already have it, but you can’t start from nothing. If you’re lacking in self-confidence and then fail at something, you won’t get that boost of additional confidence you’re looking for and will find you less likely to try again, whether it’s a new sparring move or a complicated experiment. A good sensei will work on developing your confidence from within, finding where you’re most comfortable, and figuring out how to help you shine without having to rely on your results to give you the boost you need. The positive side is that if your own confidence has been boosted, you’ll feel good enough to try new things, to explore new ideas, and you won’t be as afraid to fail the next time around. Both require you to take a lot of hits before you learn how to fight back. I spent 8 years on hiatus from tae kwon do and I came back into the sport only as a post-doc during the past two of years. Some of my muscle memories for techniques and forms stayed in place, and I’m also in better physical strength than when I started 14 years ago. But it didn’t mean that I was ready to jump back into being a black belt, since there were still quite a few places where my lack of practice and instincts were apparent. As an example, in free sparring I’ve become much better at attacking than when I first started, in conjunction with the downside that I’m still getting hit quite a lot since I didn’t build up my defenses to the same level as my attacks. In science, there are numerous occasions when your strengths and instincts will be tested. Hard-line questions and critiques by your graduate committee, advisor, conference audience, and lab mates, and you’ll essentially be dealing with an onslaught right from the get-go. It can leave you reeling and hurt, as if you were in your own intense sparring session. But the thing I’ve learned about sparring is that even if you’re not perfect, the next time you fight you won’t get hit in the same place again. You learn (even if it has to be the hard way) what parts of your work are the weak points and what you can do to make the weak points stronger. A career in research isn’t about putting up a good fight 100% of the time or only retreating from others: it’s about knowing how to move forward but also to protect yourself and foster your ideas and work at the same time. Both can be used to let your strengths shine, whatever they might be. One of my favorite things about martial arts is that it’s a sport that can be done by more than one type of person. Regardless of your body type, natural strength/flexibility, height, or weight, you can be good at martial arts and can get your black belt. In my class I’ve met other students who are extremely fast, flexible, strong, or just plain fearless. I’ve seen people who are good at sparring, who excel at forms and technique, or who are just brave enough to try anything crazy-and to me, they are all amazing martial artists. I also love that in science, despite being thought of as a place where only geniuses and nerds can succeed, you meet so many kinds of people. Some are great writers, others give amazing conference presentations, and others are wonderful group leaders or efficient lab managers. You don’t have to fit a cookie cutter ideal of what a scientist is in order to be a good one. In science as in the martial arts, what’s important is fostering the strengths you have and recognizing what you need to work on and how you can better complement your skillset. In both martial arts and in research, I somehow ended up becoming something of a jack-of-all-trades. I enjoy all aspects of both martial arts (forms, technique, flexibility, strength, sparring, and ferocity) and science (lab work, data analysis, reading, writing, meetings, and tweeting) without really excelling at one aspect or another. Sometimes I feel like I’m less skilled than others who have a more obvious specialty, whether it’s while sparring with someone who is faster than I am or when asking my lab mates to help me troubleshoot R code. But thanks to my own confidence in both parts of my life, I’ve been able to recognize that that’s just who I am and I value the way I work and live, even on the days when I come home exhausted from an intense work-out or a long day in labs. I’m thankful for the life lessons provided by both of my primary activities, and in the tough times I look ahead to days when my bruises are few and my manuscripts are many!

I tend to get in trouble by our lab safety officer once every two weeks for not wearing a lab coat. I always wear one when working with some dangerous or caustic chemicals, but most of my time spent in a molecular biology lab isn’t hazardous to my health. The main reason that I don’t like to wear a lab coat when it’s not necessary is maybe an unusual one: I don’t want to look like a scientist. Even as a researcher who’s been working in a lab for the past 8 years, I don’t want to fit the stereotype of what a scientist looks like or acts like. But what is the stereotype of a scientist? How do they look and, most importantly, how do they act?

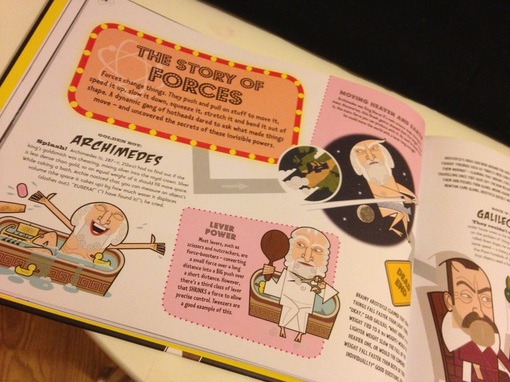

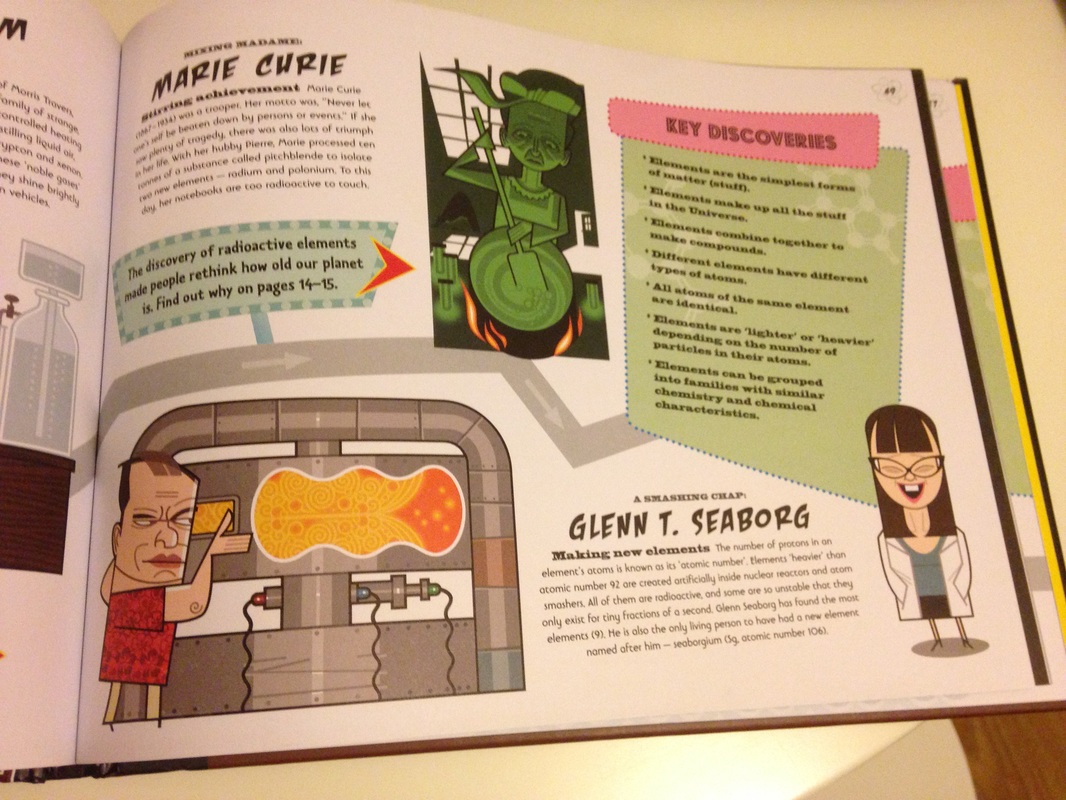

During this summer of lab work, writing, and tweeting, I’ve also been thinking about the ‘big gap’ in science, the gap between what the public thinks of what we do versus our actual research. PhD comics author Jorge Cham does a great job talking about this gap in his TEDxUCLA talk. Cham gives an example of good science communication in a collaborative project to develop a cartoon and video about the Higgs Boson. He makes note that this approach to sharing science took a lot of initiative from the scientists themselves, and it didn’t follow the traditional way of how science is shared with the broader community. Cham also comments on how shows like Big Bang theory portray researchers as eccentric and socially inept, which paints an inaccurate picture of scientists and can make the job seem unattractive to young students who don’t consider themselves geniuses or ‘nerds.’ While I do enjoy Sheldon’s banter on Big Bang Theory (because we all know someone like Sheldon in our group of colleagues or friends), I wonder if there’s a better way to talk about who scientists are and what they do. These wonderings led me to buy the children’s book, Rebel scientists, last week from Amazon. Rebels play a prominent role in modern-day storytelling: whether it’s Star Wars, Hunger Games, Braveheart, the Matrix, or the French and American revolutions, we all love to cheer for the rebels and the underdogs, be they real or fictional. But can scientists really be a part of this adjective? Dan Green’s book was one of the winners of the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize for this year. The illustrations, done by David Lyttleton, are a real treat for the eyes and help to focus the storytelling on the scientists themselves and how their work fits into the picture of our understanding of the universe. The book starts off with the timely question of “What is this thing called science?” and Dan describes it in four parts: curiosity, disagreement, discovery, and a long journey. Scientists are the ones who are curious about how the world around them works. They go against the consensus and the status quo when need be. They know that the world has a lot of mysteries that lie ahead and are driven by asking the why and how of everything and anything. Each science subject is presented as a separate chapter called “The story of ____”, with topics including the solar system, the atom, light, the elements, and genetics. Within each story, Dan starts with the early earliest thinkers and their ideas about how the world works, following through to what we know and are working on in science today. The book depicts the scientific exploration using a diagram of a road which connects discoveries together, while also provides road signs that the reader can follow to link to relevant material in other fields. The road even has the occasional dead end at an explanation of an idea that didn’t quite pan out. While the book is meant for a slightly older reader, probably for students ages 10-14, I’m amazed with the breadth of topics that are covered-and even complex subjects like quantum physics that I even had to re-read a couple of times to get the gist of the story. Below you can find a couple photos from inside the pages so you can get a sense of how the story of science and scientists are told by Dan:

I like how the book describes the Galileo’s and Einstein’s of our world: instead of calling them all geniuses or describing them as hyper-intelligent, the famous thinkers of our world are described with a wider breadth of words. ‘Rock star’, ‘radical’, rabble-rousers’, ‘sharp suited’, and ‘mavericks’ are just a few of the adjectives used. There are stories of disagreements between the biggest minds in science and how they came to a consensus about how the world works. There are stories of researchers going against the grain to pursue their ideas and delve into the mysteries that the rest of the world wasn’t able to see. At the end of the book, you can feel like the moniker of a ‘rebel scientist’ isn’t that far from the truth.